A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket roared to life and soared through the dark California skies early Wednesday, carrying a small probe that could teach NASA how to save Earth from dangerous asteroids.

NASA isn't aware of any asteroids headed for Earth in the next 100 years. But the agency expects enormous space rocks to approach our planet eventually, and it has a plan to nudge them away.

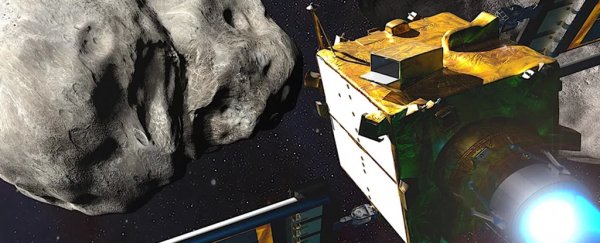

A new spacecraft – a mission called the Double Asteroid Redirection Test (DART) – is testing that plan. Its sole job: to crash head-on into the center of a distant asteroid.

The probe, a box smaller than a golf cart, lifted off aboard the Falcon 9 at 1:21 a.m. ET on Wednesday. Once the rocket releases it into space, the DART spacecraft will spend about two hours unfurling its solar panels.

If that goes smoothly, the probe will be hurtling toward a pair of asteroids. One, a moonlet called Dimorphos, orbits the other, Didymos. DART is aiming for the moonlet, which is about as big as a football stadium. It's set to reach its target, 6.8 million miles from Earth, in September 2022.

"We're going to hit it hard, but we're hitting it with a very small vehicle," Ed Reynolds, the DART project manager at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, said in a press conference on Monday.

"When we're looking at what does it take to deflect an asteroid away from Earth – given enough time, you can do big things with small vehicles."

That nudge should be just enough to push Dimorphos closer to Didymos, causing it to orbit the larger asteroid about 10 minutes faster than before – every 11 hours and 45 minutes instead of every 11 hours and 55 minutes.

If it succeeds, DART will prove that technology can change the paths of dangerous asteroids. It will also provide NASA with valuable data about how the collision affects the asteroid and how big a probe must be to move its target.

"I could imagine, for example, that we have a series of such impactors – a small number – that are actually in orbit and ready to go in case a threat occurred," Thomas Zurbuchen, an associate administrator at NASA, said in a pre-launch press conference Monday.

DART's final hour will make or break the mission

NASA isn't tracking every space rock in our neighborhood of the Solar System. Astronomers have identified an estimated 40 percent of nearby asteroids that are 140 meters wide or larger – those big enough to level a city. Dimorphos, at 160 meters, is a perfect model of such a city killer.

But other than its size and how quickly it orbits Didymos, scientists know little about their target. They can't see it directly with telescopes on Earth, instead gleaning information from changes in Didymos's light as the moonlet passes between the larger asteroid and Earth.

(ESA-Science Office)

(ESA-Science Office)

Above: The 160-m diameter Dimorphos asteroid compared to Rome's Colosseum.

NASA won't even know what shape Dimorphos is until DART's camera catches sight of it about an hour before collision.

As Dimorphos comes into view, a spacecraft system called SMART Nav is programmed to rapidly calculate the looming asteroid's center. Then the probe's navigation system will fire its thrusters to steer it to the target.

During its final approach, DART is programmed to beam a new photo back to Earth every second. A small Italian spacecraft, LICIACube, is set to release itself from DART 10 days before collision, fly alongside the NASA probe, and record the crash.

The spacecraft should hit Dimorphos's center at 15,000 miles (24,140 km) per hour (4 miles, 6 km per second), transferring its kinetic energy to the asteroid and pushing it closer to Didymos.

NASA estimates that the impact will cause an explosion of between 22,000 and 220,000 pounds (99,790 kg) of rock material, which could give the asteroid an even bigger push than DART itself.

The European Space Agency plans to launch a follow-up mission, called Hera, to examine Didymos and Dimorphos in 2026. In addition to studying the aftermath of the impact, Hera will map Dimorphos, precisely measure its mass, and examine the crater DART leaves there.

Nudging an asteroid only works if NASA has enough time to reach it

In order to use a DART-like mission to divert an Earth-bound boulder, NASA needs about five to 10 years' advanced notice of an asteroid's advance, experts previously told Insider.

That's because it takes years to design and build a spacecraft, then months or years to travel to the asteroid. What's more, the probe likely needs to hit an asteroid a year or two before its orbit intersects with Earth. The slight nudge of a spacecraft impact only takes the rock slightly off course at first. But over time, that change carries it further away from Earth.

In order to identify hazardous asteroids with enough lead time, NASA is building a space telescope called Near-Earth Object Surveyor to monitor large asteroids orbiting the Sun near Earth. NASA hopes the telescope will identify 90 percent of asteroids 140 meters or larger.

"If we don't find these objects that could be an impact threat to the Earth – a hazard to the Earth – we can't do anything about them," Lindley Johnson, NASA's planetary-defense officer, said in the Monday briefing.

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: