Becoming a new parent is full of unknowns that nothing in life can prepare you for. But for would-be parents considering assisted reproductive technologies to overcome fertility issues, having a realistic expectation of their chances of falling pregnant and how long it might take is the bare minimum given what's at stake.

New data compiled by Australian researchers shows most people need more than one cycle of in vitro fertilization (IVF) for a reasonable chance of success and that those odds plummet the older you get.

Women who started IVF at age 40 had just a 13 percent chance of having a baby after one cycle, whereas women who started treatment either in their mid-30s or before turning 30 had a 40 and 43 percent chance, respectively.

Across all age groups, the chances of having a baby rose with each consecutive cycle of IVF, but those chances still trended downward with age.

Women starting treatment at 35 had a success rate of around 60 percent after three IVF cycles, the analysis found. This dropped to 25 percent after three rounds for women aged 40 years.

Given that age is the single biggest factor affecting fertility, the trends are to be expected. The data are important because people tend to overestimate their chances of success with IVF, possibly buoyed by the fact that overall success rates have risen over the past decade with incremental improvements in technology.

These latest figures are based on the live birth rates of thousands of women who started IVF in 2016 in the Australian state of Victoria. The researchers tracked birth outcomes over five years to 2020, to produce an estimate of how likely women are to have a baby after completing one, two, or three rounds of IVF.

Fertility researcher Karin Hammarberg of Monash University said the new batch of data shows IVF should not be viewed as an 'insurance policy' and that people wanting a baby should try as early as they can.

Hammarberg is also affiliated with the Victorian Assisted Reproductive Treatment Authority, which regulates fertility treatment providers and commissioned the research as part of its annual reporting. The data is not peer-reviewed but aligns with national statistics.

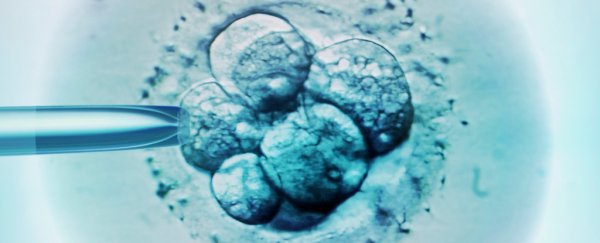

A typical cycle of IVF involves stimulating a woman's ovaries to produce eggs, which are collected, fertilized in a dish to create budding embryos, and transferred back to the womb.

Too often, though, doctors focus on women's fertility and neglect men's health or age.

Research shows that men's chances of a baby through IVF drop about 4 percent every year, no matter the age of their female partner, although other studies have put an upper limit on this trend.

"It is important that both men and women are aware of the impact that age has on fertility and that IVF cannot fully overcome infertility due to advancing age," says Luk Rombauts, a fertility specialist at Monash University.

Like women, men's fertility starts declining around age 40, and by the age of 45, it can take men five times longer to conceive than it would have in their 20s.

It's important to note that these population-level data don't take into account individual factors that affect one's chance of IVF success. This includes a couple's general health, weight, other factors impacting fertility such as endometriosis, and how many eggs a woman has in reserve (this drops with age).

The data also didn't capture the couples who decided to stop treatment. IVF is expensive, costing thousands of dollars each round, not to mention painful, often disappointing, and emotionally fraught.

Worldwide trends in IVF births also paint a more complete picture than the Australian data. A 2019 study suggests IVF birth rates peaked around 2001, plateaued thereafter, and have been declining in most parts of the world.

Writing in their paper, obstetrician-gynecologist Norbert Gleicher of the Rockefeller University, New York, and two colleagues argue that increasing IVF costs, the 'regrettable' use of 'add-on' procedures backed by little evidence, and falling success rates have led to lower satisfaction.

"Over the past decade and a half, IVF… has increasingly disappointed outcome expectations," Gleicher and colleagues write.

"As especially Australia's experience suggests, such developments may lead to higher prices, poorer clinical outcomes, and decreasing patient satisfaction," they add.

Concerns about the lack of transparency in the IVF industry are also widespread. Australian clinics, for example, aren't required to publish their success rates, making it practically impossible for would-be parents to compare services.

"There is no set rule for how to report success, so clinics do it in different ways, and it makes it completely confusing for patients," Hammarberg told Olivia Willis at the Australian Broadcasting Corporation in 2019.

Only with all the information can people best prepare for the unknown.

The data is published annually by the Victorian Assisted Reproductive Treatment Authority.