Having the technology and know-how to get to other planets is one thing, but can we keep the human race going when we start living beyond our Earthly habitat for years on end? According to a new series of experiments carried out by Chinese researchers, the answer is yes.

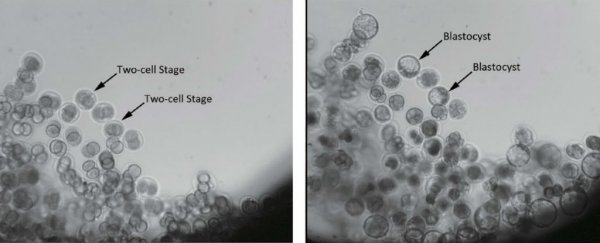

The experiments were carried out on mouse embryos aboard China's microgravity SJ-10 satellite, launched earlier this month. The embryos have been shown to successfully develop into blastocysts - the stage right before the embryo plants itself into the uterine wall.

It's the first time mammalian embryos have successfully developed in space, and it hints at the potential for humans to breed successfully in space as well. The stage that the scientists are focused on here is one of the most crucial in the development of the embryo.

"The human race may still have a long way to go before we can colonise space, but before that we have to figure out whether it is possible for us to survive and reproduce in the outer space environment like we do on Earth," principal researcher Duan Enkui from the Chinese Academy of Sciences told China Daily.

The findings so far suggest that yes, it is.

The mouse embryos (all 6,000 of them) were carried into outer orbit inside a self-sufficient, enclosed chamber about the size of a microwave oven - a setup that had undergone extensive testing on the ground. Enkui and his team are monitoring the development of the cells through photos beamed back to Earth every 4 hours.

The timing of the embryonic progression, which was reached in around 96 hours, is about the same as on Earth. As The Telegraph reports, previous attempts by NASA to develop mammalian embryos in space failed, as did a Chinese-led experiment run in 2006.

There are 20 different ongoing experiments on board SJ-10, and Jamie Condliffe at Gizmodo reports that the satellite is going to return to Earth in a few days. At that point, the embryos can be analysed further to see if there are any major differences between their development on Earth and their development in space.

Stanford University reproductive biology expert, Aaron Hsueh, who was not involved in the research, said the results of the experiment were "an important milestone" for space science. "One small step for mouse embryos, one giant leap for human reproduction," he told China.org.cn.

The right conditions and healthcare needed for rearing babies in space remain a mystery, but it's now looking like it's possible, which means one day in the future, a child might well grow up without any knowledge of life on Earth.