Long before TV shows like CSI made us aware of high-tech forensic techniques at crime scenes, pretty much everybody already had some basic familiarity with the concept of fingerprinting, an identification method with roots going as far back as the 19th century.

While fingerprinting is still a thoroughly useful method for discovering who may have been present at the scene of a crime, the basic premise of the technique used by crime scene investigators – visual comparisons between two sets of fingerprints – hasn't changed in a very long time. However, a new way of taking people's prints not only records what their fingerprints look like, but could help investigators determine whether the person was a man or a woman – and maybe even a lot more about them too.

"Fingerprints have really been treated as pictures for more than a hundred years," Jan Halamek, a forensic scientist at the State University of New York at Albany, told Sindya N. Bhanoo at The New York Times. "The only major improvements in recent years have been due to software and databases that make it faster to match fingerprints."

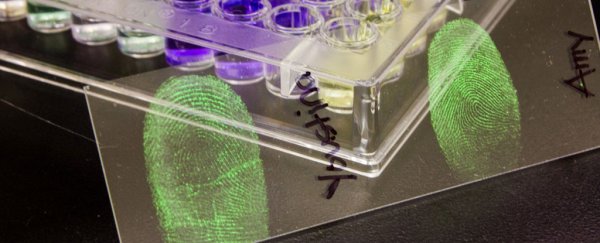

Halamek and fellow researchers have instead developed a system where fingerprints aren't just treated as visual records. Rather, the sweat deposits left in fingerprints are analysed for their biochemical content – specifically, the amino acids they contain, which can reveal the sex of the person who left the print. This is because the levels of amino acid in female sweat are about twice as high as that of males.

It's not the first time scientists have run biochemical analyses on fingerprints, but the early results of the researchers' methods are promising, with the technique giving a 99 percent chance of correctly identifying whether prints are male or female.

In addition to testing their system on a series of 50 mimicked fingerprint samples, the researchers ran the procedure on a very small sample group of three males and three females.

When doing so, the team was able to successfully distinguish between the fingerprints of male and female subjects on a number of surfaces, including a polyethylene sheet, a door knob, a laminated desktop, a composite bench top, and a computer screen. The findings are published in Analytical Chemistry.

To extract the amino acids, the researchers transfer the print to a polyethylene film, separating the amino acids from the lipids with a drop of diluted hydrochloric acid. The amino acid levels are then measured using an enzyme-based colorimetric test. Compared to other means of analysing prints, such as mass spectrometry, it's relatively simple and inexpensive to perform.

The researchers acknowledge they'll need to replicate their findings with a larger sample, but also hope to refine the system and develop means of finding out even more about a person based on their fingerprint, using other bio-markers in addition to amino acids. As Halamek told Bhanoo, "We want to create a very simple kit which can determine on the spot whether the person was young or old, male or female, and their ethnicity."