A new test helps predict which kids face the largest genetic risk of a high body mass index (BMI) later in life. That could help parents establish healthy habits early on.

The new test, put together by a large team of international researchers, is what's known as a polygenic score or PGS. These scores are used to group genetic variations to predict a certain characteristic, which in this case is BMI.

Related: Just 5 Days of Junk Food Can Trigger Obesity's Hold on Your Brain

"What makes the score so powerful is its ability to predict, before the age of five, whether a child is likely to develop obesity in adulthood, well before other risk factors start to shape their weight later in childhood," says genetic epidemiologist Roelof Smit, from the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

"Intervening at this point can have a huge impact."

It's important to note that the test isn't quite as straightforward as it might sound. For one, genetics only accounts for a relatively small proportion of risk for high BMI. And secondly, a growing body of research is suggesting we move away from BMI as a measure of obesity and health in general.

Still, the researchers claim the new PGS test is up to twice as accurate as others of its type. It was built from a database of genetic information collected from more than 5.1 million people.

After compiling the test, the researchers then tried it out on several separate health databases, covering hundreds of thousands of individuals. In these datasets, both genetic data and BMI over time had been recorded.

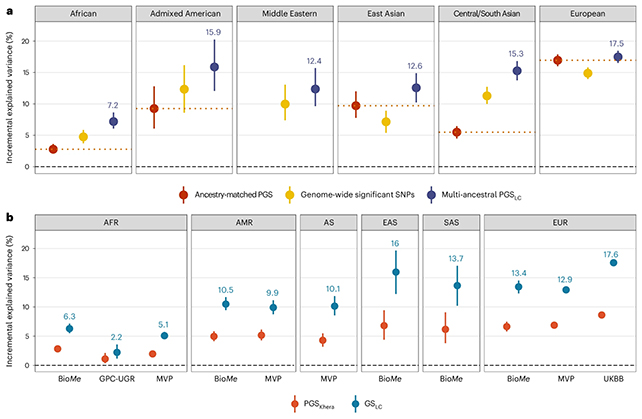

The researchers added the PGS to other predictors of BMI, and found that higher PGS scores were associated with greater adult weight gain. The accuracy of the PGS at predicting BMI variation depended on age and ancestry.

PGS scores at the age of 5 explained 35 percent of the BMI variation at age 18. For middle-aged Europeans, it accounted for 17.6 percent of the variation.

In other groups it was much lower: just 2.2 percent for rural Ugandans, for example. This is probably down to underrepresentation in the training data, and the greater genetic diversity in African populations, the researchers say.

Another interesting finding from the study: those with stronger genetic predisposition towards having a higher BMI actually lost more weight during the first year of weight loss programs, although they were also more likely to regain weight later.

"Our findings emphasize that individuals with a high genetic predisposition to obesity may respond more to lifestyle changes and, thus, contrast with the determinist view that genetic predisposition is unmodifiable," write the researchers in their published paper.

The thinking is that if BMI can be predicted more accurately at an early age, that gives those kids and their parents a bigger window of time to instill healthier habits regarding diet or activity levels, which have the potential to influence BMI.

"This new polygenic score is a dramatic improvement in predictive power and a leap forward in the genetic prediction of obesity risk, which brings us much closer to clinically useful genetic testing," says geneticist Ruth Loos, from the University of Copenhagen.

The research has been published in Nature Medicine.