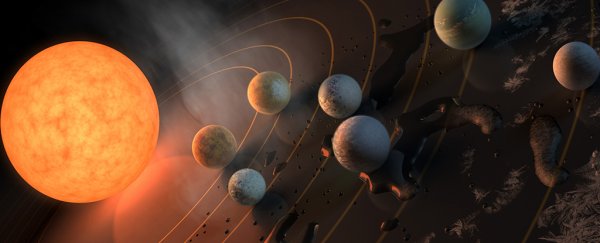

Since we first spotted the TRAPPIST-1 system in February, scientists have been scrambling to learn more about these seven rocky planets circling around their red dwarf star – but research suggests the planets aren't as hospitable as we'd hoped.

Two more reports on TRAPPIST-1 again identify challenging conditions that would make it difficult for extraterrestrial life to take hold: dangerous ultraviolet radiation from the dwarf star and a lack of a magnetic field cover.

According to the two teams from the Harvard-Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics we shouldn't give up looking for signs of life in the TRAPPIST-1 systems, but they estimate the chances of complex life being there as very slim.

Of the seven rocky planets orbiting the TRAPPIST-1 star, three are right inside what technically qualifies as the habitable zone – a sweet spot between the warmth of a star and the coldness of deep space where conditions might be just right for liquid water to pool and, perhaps, life to evolve.

TRAPPIST-1 itself is fainter and less massive than the Sun, but its planets are closer in orbit than Earth, so the sums might just work out.

"The concept of a habitable zone is based on planets being in orbits where liquid water could exist," says one of the team behind the first experiment, Manasvi Lingam. "This is only one factor, however, in determining whether a planet is hospitable for life."

Lingam and his Avi Loeb ran models of the kinds of levels of UV radiation TRAPPIST-1 would be beaming out, and suggest the radiation would be hitting the surrounding planets with a far greater level of intensity than we're used to on Earth, sunblock or no sunblock.

"Because of the onslaught by the star's radiation, our results suggest the atmosphere on planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system would largely be destroyed," says Loeb. "This would hurt the chances of life forming or persisting."

A lack of atmosphere was also highlighted as a problem in the second study, which looked at the effects of solar winds coming from TRAPPIST-1.

Solar particles from the red dwarf star are hitting its planets at levels between 1,000 and 100,000 times greater than we get hit by solar winds from the Sun, report the scientists.

What's more, because the planets and TRAPPIST-1 are so close, their magnetic fields might well be joined together – and so the planet surfaces won't have the same protection as we do here on Earth.

As a result the atmospheres of the planets surrounding TRAPPIST-1 could've been stripped right off, making it very unlikely that anything living would be able to survive.

"The Earth's magnetic field acts like a shield against the potentially damaging effects of the solar wind," says the lead researcher of the second study, Cecilia Garraffo. "If Earth were much closer to the Sun and subjected to the onslaught of particles like the TRAPPIST-1 star delivers, our planetary shield would fail pretty quickly."

These computer models are a reminder that a planet needs more than optimal conditions for liquid water to support life. In fact, it's sort of amazing that we're here at all.

The new research backs up earlier studies on solar flares and harmful radiation that also suggest the chances of finding alien civilisations in the TRAPPIST-1 system are pretty slim – but that doesn't mean we should stop looking.

"We're definitely not saying people should give up searching for life around red dwarf stars," says one of the team, Jeremy Drake. "But our work and the work of our colleagues shows we should also target as many stars as possible that are more like the Sun."

The studies have been published in the International Journal of Astrobiology and the Astrophysical Journal Letters.