For 430 million years, nestled in some rocks in England, Cthulhu waited, dreaming. Now it's finally seen the light of day, and it's honestly a lot smaller than we were expecting.

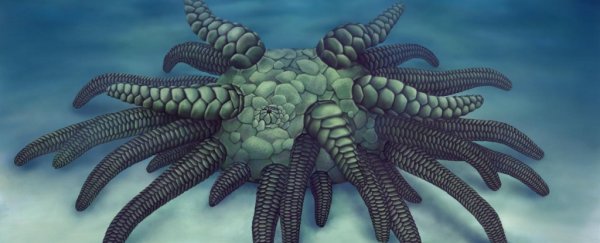

This fossilised Cthulhu is related to sea cucumbers, and dates back to the Silurian period, when the first bony fish appeared. Its three-centimetre (1.1 inch) body was entirely covered in bony plates, and bristling with 45 armoured tentacles, which it likely used to capture food and scuttle across the seafloor.

It's for these features that the palaeontologists who discovered the beast gave it the name Sollasina cthulhu, in honour of horror writer HP Lovecraft's famous be-tentacled god.

The tiny fossilised beastie was exquisitely preserved.

"In this paper, we report a new echinoderm - the group that includes sea urchins, sea cucumbers, and sea stars - with soft-tissue preservation," said palaeontologist Derek Briggs of Yale University.

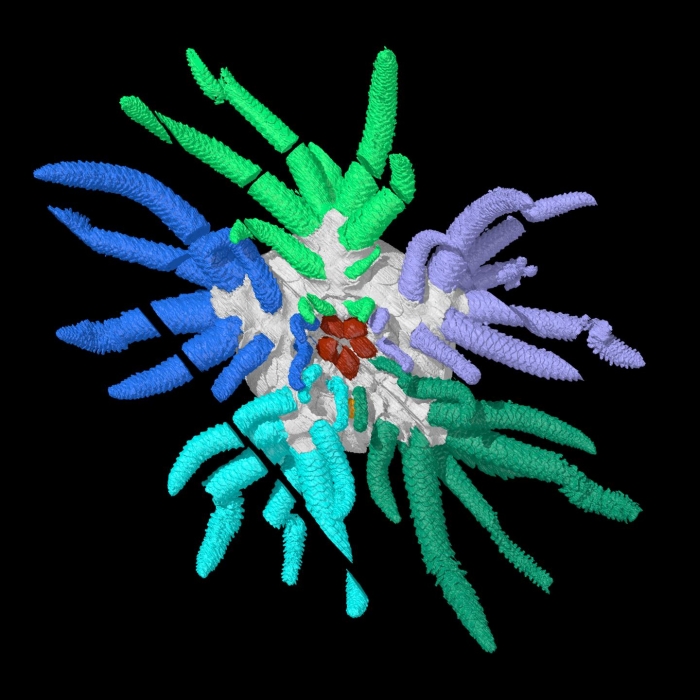

"This new species belongs to an extinct group called the ophiocistioids. With the aid of high-resolution physical-optical tomography, we describe the species in 3D, revealing internal elements of the water vascular system that were previously unknown in this group and, indeed, in nearly all fossil echinoderms."

To reconstruct the fossil, the team had to destroy it. Layer by thin layer, they ground the fossil away, taking detailed photographs at each stage. These photographs can then be used in a manner similar to multi-slice imaging to reconstruct the animal in 3D.

The 3D reconstruction. (Imran Rahman, Oxford University Museum of Natural History)

The 3D reconstruction. (Imran Rahman, Oxford University Museum of Natural History)

This approach allowed the team a detailed look at the animal's innards, where they found a structure called the ring canal.

In echinoderms, this is a circular tube central to the vascular system that moves water through their bodies. This system allows the animals to move hydraulically, rather than using muscles.

Such a ring canal has never before been seen in an ophiocistioid. The researchers interpreted it as the first evidence of a water vascular system in the class, placing them closer to sea cucumbers than sea urchins, as previously believed.

But sea cucumbers don't have armoured bodies - they're soft and squishy. This, the researchers said, suggests that ophiocistioids branched away from the lineage that produced today's sea cucumbers to do their own thing.

Maybe they continued evolving. Maybe they're still down there somewhere. In R'lyeh. Waiting. Dreaming.

The research has been published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B.