Scientists have stumbled upon an extraordinary 'living drug' in the bloodwork of a late-stage cancer survivor.

A year after receiving "the biggest development in cancer therapy" in over 50 years, this patient's body was still protected by a fleet of souped-up killer immune cells known as T-cells.

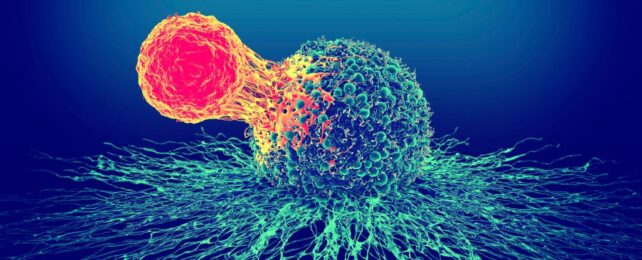

Researchers at Cardiff University in the UK found that these special T-cells may be much better at recognizing and attacking tumors than average T-cells.

They could even take down multiple different types of cancer from various angles at once.

"Our findings really surprised us as nobody knew that individual T-cells could recognize cancer cells via several different cancer-associated proteins simultaneously," explains Cardiff University biologist Andy Sewell.

"We wanted to know how some patients with end-stage cancer who had been treated with [tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte] therapy successfully cleared their cancer, so we went hunting for answers."

In the last decade or so, tumor-infiltrating lymphocyte (TIL) therapy has emerged as a powerful new way to possibly eradicate late-stage tumors.

TIL therapy involves taking a patient's own white blood cells directly from their tumor and growing and artificially enhancing them to better attack cancer.

In clinical trials, the therapy seems to work more than 80 percent of the time.

Despite these incredible results, scientists still don't know how the therapy works on a cellular level.

Researchers at Cardiff have been trying to figure that out for years, and now, they've had a breakthrough.

When examining the results of phase I and II clinical trials, in which 31 patients with malignant melanoma received TIL therapy, researchers found those who successfully cleared their cancer still showed strong T-cell responses over a year later.

The T-cells from one of these patients were remarkably 'multi-pronged', showing the potential to respond to most types of cancer, not just melanoma.

"Importantly, we have seen large numbers of multi-pronged T-cells in the blood of cancer survivors," says Sewell.

"To date, we have not found such multi-pronged T-cells in people where cancer progresses."

To confirm what's really going on, Sewell and his colleagues must now carefully watch these multi-pronged T-cells attack cancer in the lab.

Only then will they be able to determine whether these immune cells are responsible for the great outcomes of TIL therapy.

"[W]e hope to investigate whether engineered multi-pronged T-cells can be used to treat a wide range of cancers in a similar way to how engineered CAR-T cells are now used to treat some types of leukemia," says one of the lead authors, Cardiff University immunologist Garry Dolton.

CAR-T cells are chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies, and they are already approved as a treatment for blood cancer by the US Food and Drug Advisory.

CAR-T therapy differs slightly from TIL therapy because it reprograms specific T-cells to target certain parts of a cancer cell.

Because TIL T-cells come straight from a solid tumor, they are more diverse, and scientists don't need to fiddle with their attack mechanisms nearly as much.

Perhaps this is what makes them so effective against so many types of cancer.

"Patient numbers are small so far, but it remains possible that multi-pronged T-cells might be associated with complete remission – or cancer clearance," hopes Sewell.

The study was published in Cell.