Drug-resistant germs sicken about 3 million people every year in the United States and kill about 35,000, representing a much larger public health threat than previously understood, according to a long-awaited report released Wednesday by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The new estimates show that, on average, someone in the United States gets an antibiotic-resistant infection every 11 seconds, and every 15 minutes, someone dies.

Bacteria, fungi and other germs that have developed a resistance to antibiotics and other drugs pose one of the gravest public health challenges and a baffling problem for modern medicine.

Scientists, doctors and public health officials have warned of this threat for decades, and the new report reveals the top dangers and troubling trends. More pathogens are developing new ways of fending off drugs designed to kill them, and infections are spreading more widely outside of hospitals.

No new classes of antibiotics have been introduced in more than three decades.

The report highlighted some successes. Hospitals have improved their methods for tracking and slowing the spread of resistant germs, and deaths from superbug infections there have decreased by nearly 30 percent since 2013.

Experts say everyone can help control many of these pathogens by practicing basic prevention: good hand hygiene, vaccination, safe food handling and safe sex.

In addition to germs that have evolved drug resistance, the report included a dangerous infection that is linked to antibiotic use: Clostridioides difficile (C. diff.).

It can cause deadly diarrhea when antibiotics kill beneficial bacteria in the digestive system that normally keep it under control. When the C. diff. illnesses and deaths are added, the annual US toll of all these pathogens is more than 3 million infections and 48,000 deaths.

The CDC had previously estimated about 2 million antibiotic resistant infections and 23,000 deaths in a 2013 report. The new report used previously unavailable data, including electronic health databases from more than 700 acute-care hospitals.

By applying the new methods retrospectively, the CDC calculated that the 2013 estimate missed about half of the cases and deaths.

"A lot of progress has been made, but the bottom line is that antibiotic resistance is worse than we previously thought," said Michael Craig, the CDC's senior adviser on antibiotic resistance.

The new numbers, though still conservative, underscore the magnitude of the problem, establish a new national baseline of infections and deaths, and will help prioritize resources to address the most pressing threats, infectious diseases experts said.

These germs spread through people, animals and the environment.

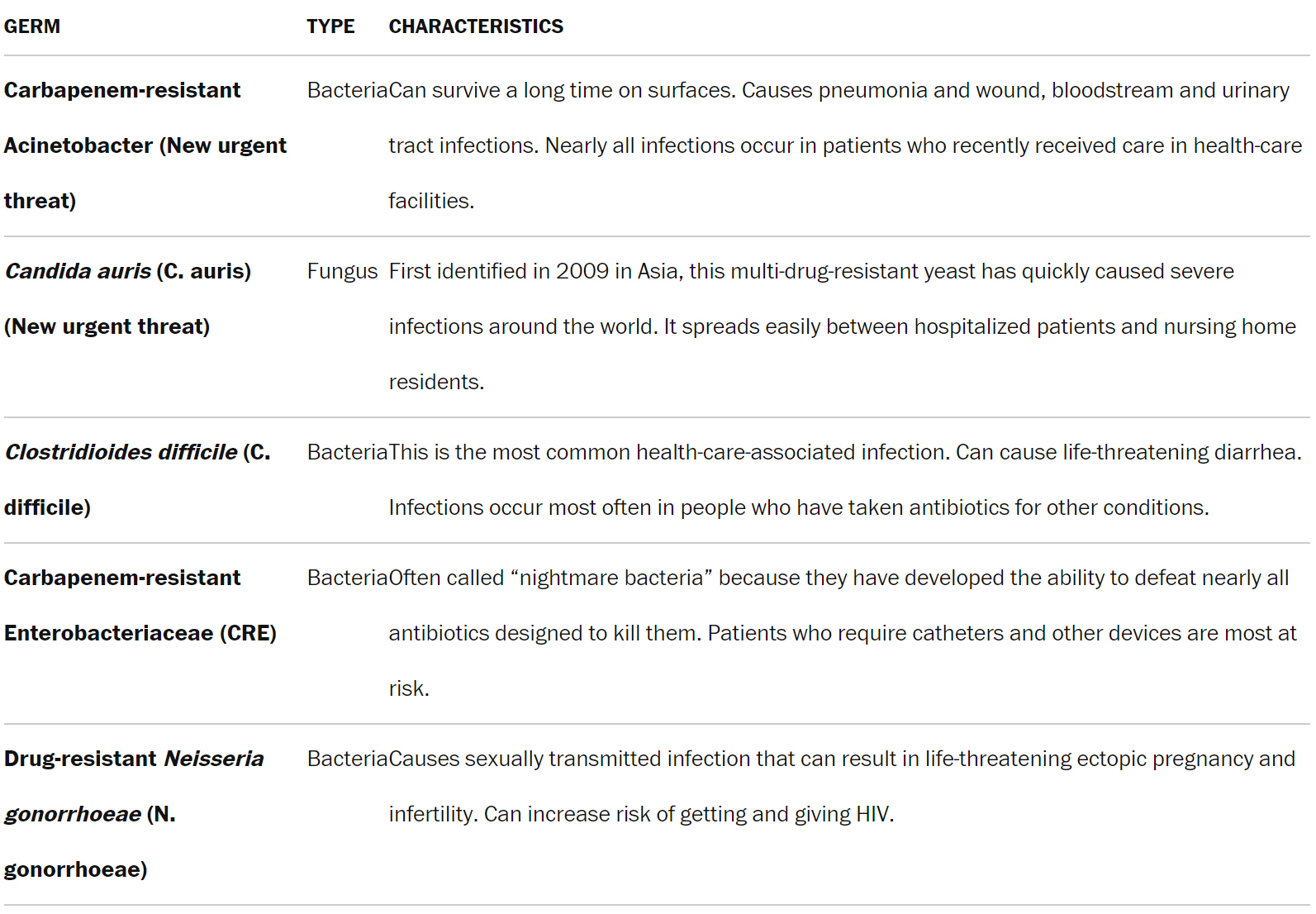

The report details the toll that 18 pathogens are taking on humans, ranking the threat of each as "urgent", "serious" or "concerning".

Five germs account for the most urgent threats. Three are long-recognized dangers: C. diff., drug-resistant gonorrhea, and carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae (CRE), also known as "nightmare bacteria" because they pose a triple threat.

They are resistant to all or nearly all antibiotics, they kill up to half of patients who get bloodstream infections from them, and the bacteria can transfer their antibiotic resistance to other related bacteria, potentially making the other bacteria untreatable.

Two new germs were added to the urgent category since the CDC's 2013 report: a deadly superbug yeast called Candida auris that has alarmed health officials around the world and a family of bacteria, carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter, that has developed resistance to nearly all antibiotics.

The CDC also added a new category in addition to the ones used to classify the 18 pathogens: a watch list of three germs that officials are monitoring because they have the potential to spread resistance widely or are not well understood in the United States.

They are a life-threatening fungus, azole-resistant Aspergillus fumigatus; a sexually transmitted infection called drug-resistant Mycoplasma genitalium; and drug-resistant form of Bordetella pertussis, commonly known as whooping cough, which can be prevented with a vaccine.

The report cites two worrisome trends: the increasing numbers of resistant infections outside hospitals, including highly drug-resistant gonorrhea; and the increasing ability of drug-resistant microbes to share their dangerous resistance genes with other kinds of bacteria, making those other germs untreatable, as well.

Antibiotic resistance is particularly deadly for patients in hospitals and nursing homes, and those with weak immune systems. But these hard-to-treat infections now threaten people undergoing common modern surgeries and therapies, such as knee replacements, organ transplants and cancer treatments.

"We see people from everyday life, who are young and otherwise healthy, who get a MRSA [methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus] infection on their skin," said Helen Boucher, chief of infectious diseases at Tufts Medical Center, who cares for many transplant patients who are vulnerable to these infections, which the CDC lists as a serious threat.

If a young and otherwise healthy woman gets a urinary tract infection from another type of bacteria listed as a serious threat, ESBL-producing enterobacteriaceae, "all we can offer is an intravenous antibiotic for 10 to 14 days" because clinicians no longer have other effective treatments, Boucher said.

The intravenous antibiotic can be administered at home. But it requires a catheter to be inserted into a vein, a procedure that also poses an infection risk, she said.

"We want to have diagnostic tools and medical treatments for problems we know we're going to have," she said.

"But we also need to prepare for the kind of resistance that we could never predict. We know from history that bacteria and Mother Nature are smarter than we are."

It's difficult to estimate the number of drug-resistant infections, because no comprehensive surveillance system or database exists. Antibiotic resistance also isn't a single disease.

Other estimates find the true burden of these infections could be much higher. Jason Burnham, an infectious diseases expert at Washington University, said he and his colleagues included more pathogens and a broader definition of drug resistance in their analysis than the CDC did in its new report. Burnham's team estimated the death toll at about 153,000 annually.

Bacteria are constantly evolving to fend off the drugs used to kill them. As they mutate, some develop the ability to fight off different antibiotics and survive to multiply and spread resistance. The more antibiotics are used in health care and agriculture, the less effective they become.

Overuse of antibiotics is a likely reason for the dramatic rise in resistant infections, the report said. Nearly a third of antibiotics prescribed in doctors' offices, emergency rooms and hospital-based clinics in the United States are not needed, according to a 2016 study.

Most of them were prescribed for conditions that don't respond to antibiotics, such as colds, sore throats, flu and other viral illnesses.

"The fact that we're seeing some of the greatest increases among resistant infections that are acquired outside of the hospital - combined with data we already have showing that approximately 1 in 3 outpatient prescriptions are completely unnecessary - underscores the need for improved antibiotic use in doctor's offices and other non-hospital settings," said David Hyun, who researches and develops strategies for the Antibiotic Resistance Project at the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Among the report's other findings:

Drug-resistant gonorrhea infections have surged. More than half a million such infections occur each year, twice as many as reported in 2013.

Their increase could be an unintended consequence of the success of PrEP, the once-a-day pill that protects users against HIV infection, which may make people less vigilant about using condoms.

"People may feel very confident that they're not going to get HIV using PrEP, but that is not going to protect you from bacterial illnesses," said Craig, the CDC senior adviser.

Gonorrhea has quickly developed resistance to all but one class of antibiotics; half of all infections are resistant to at least one antibiotic. Untreated gonorrhea can cause serious and permanent health problems, including ectopic pregnancy and infertility.

ESBL-producing enterobacteriaceae are one of the leading causes of death from resistant germs. They often cause infections in otherwise-healthy people. The CDC estimates there were 197,400 cases in hospitalized patients in 2017, including 9,100 deaths.

Erythromycin-resistant group A streptococcus infections have quadrupled since the 2013 report. Currently, strep throat is not resistant to common first-line antibiotics such as penicillin or amoxicillin.

But doctors often use erythromycin and azithromycin to treat the condition, especially for people allergic to penicillin. More than 1 in 5 invasive strep infections are caused by resistant strains, limiting treatment options for patients.

One of the two new urgent threats is carbapenem-resistant Acinetobacter. The bacteria, which can cause pneumonia, bloodstream and urinary tract infections, are already resistant to many antibiotics, and frequently contaminate health-care facility surfaces and medical equipment.

But the CDC moved these germs from serious to urgent threats because they have developed resistance to the most powerful antibiotics. They also carry mobile genetic elements that can spread resistance to other germs.

The other new urgent threat is C. auris, a fungus that can cause life-threatening infections if it gets into the bloodstream. It spreads easily among hospitalized patients and nursing home residents. It is often resistant to all the major antifungal drugs.

When the CDC issued its first report on drug-resistant infections, there was no mention of C. auris because the newly discovered germ began spreading in the United States in 2015.

On Wednesday, health authorities in New York, which has been hard hit by the deadly fungus, released a report identifying the more than 170 facilities that treated patients with C. auris.

The table below lists CDC's five "urgent" threats of concern to human health:

(The Washington Post)

(The Washington Post)

2019 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.