The 2018 Nobel Prize in chemistry was awarded Wednesday to Frances H. Arnold, George P. Smith and Gregory P. Winter for their work that harnessed evolutionary principles to create new proteins.

Arnold, a professor of chemical engineering at California Institute of Technology, won one half of the prize "for the directed evolution of enzymes."

George Smith, at the University of Missouri, and Gregory Winter, at the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge in Britain, shared the other half of the prize "for the phage display of peptides and antibodies."

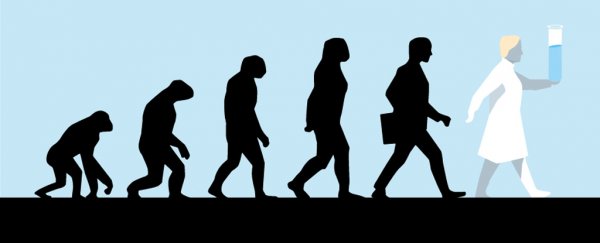

"This year's prize is about harnessing the power of evolution," said Göran K. Hansson, secretary general of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, to reporters in Sweden.

These scientists used evolutionary techniques in the laboratory to create powerful antibodies, enzymes - molecules that speed up chemical reactions - and other important biological molecules.

The award was for chemistry, but the work has wide applications throughout biology and engineering.

Arnold is one of the few people to be a member of the exclusive National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Medicine and the National Academy of Engineering. In 1993, Arnold was the first person to create new enzymes with a technique called "directed evolution."

Frances Arnold, awarded the 2018 #NobelPrize, conducted the first directed evolution of enzymes, which are proteins that catalyse chemical reactions. Enzymes produced through directed evolution are used to manufacture everything from biofuels to pharmaceuticals.@francesarnold pic.twitter.com/TGRxgjEHzv

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 3, 2018

Mutations allow the evolution of new traits and species by jumbling genetic information. Arnold introduced random point mutations in bacteria, which changed the potency of their proteins.

This, said Claes Gustafsson, chair of Nobel Chemistry Committee, was applying the "principles of Darwin in the test tube."

As humans bred animals and plants for thousands of years in agriculture by propagating the individuals with the most useful traits, Arnold selectively bred her bacteria.

After repeatedly screening and mutating those microbes, she could use them to build a more powerful version of a desired protein. The resulting molecule could be hundreds of times more potent than the original version.

These improved molecules have a wide range of applications, including brain imaging, environmentally friendly detergents, biofuels and pharmaceuticals, said biochemist Sara Snogerup Linse, a member of the chemistry committee.

In 1985, Smith developed a method called phage display, based on a kind of virus called a bacteriophage that infects bacteria.

Those viruses are little more than loops of genetic material shrouded in a protein capsule. By introducing a gene into the phage, Smith could evolve new types of proteins on that virus capsule.

2018 #NobelPrize laureate George Smith developed a method known as phage display, where a bacteriophage – a virus that infects bacteria – can be used to evolve new proteins. pic.twitter.com/roX8uOFICe

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 3, 2018

Winter applied the phage display technique to create pharmaceutical antibodies. Antibodies are the molecules that our immune cells use to recognize other cells.

Sir Gregory Winter, awarded the #NobelPrize in Chemistry, has used phage display to produce new pharmaceuticals. Today phage display has produced antibodies that can neutralise toxins, counteract autoimmune diseases and cure metastatic cancer. pic.twitter.com/p5fOfo0DwJ

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 3, 2018

These antibodies have been used to neutralize toxins, treat metastatic cancer and fight inflammatory bowel disease and other autoimmune diseases.

This was the 110th Nobel Prize awarded for chemistry since 1901. The next Nobel, the Peace Prize, will be announced on Friday.

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.