Once again, crows have demonstrated their wicked smarts by passing a cognitive test to prove they can exercise self control almost as well as a human child. Offered treats, they were able to hold off devouring available snacks if they could see an even better snack coming.

The research, conducted on New Caledonian crows (Corvus moneduloides), is the first of its kind conducted on both children and crows at the same time, the researchers said. It's based on a famous experiment conducted on children in the 1960s, called the Stanford marshmallow experiment.

In this experiment, a child is placed in a room with a marshmallow. They are told if they can manage not to eat the marshmallow for 15 minutes, they'll get a second marshmallow.

This ability to delay gratification demonstrates cognitive abilities such as future planning, and it was originally conducted to study how human cognition develops; specifically, at what age a human is smart enough to delay gratification if it means a better outcome later.

Obviously that exact experiment wouldn't work on crows - as far as we know, they can't understand human language - but luckily the experiment can be modified for animals.

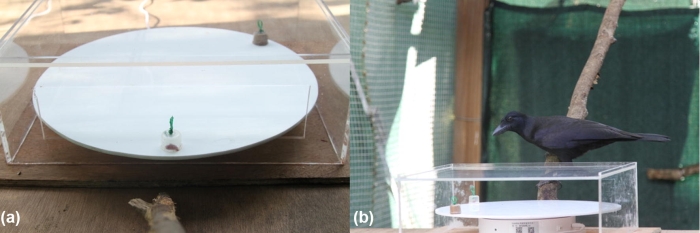

Led by psychologist Rachael Miller of the University of Cambridge in the UK, the researchers used an apparatus consisting of a rotating tray in a transparent case with a window that allows part of the tray to poke out.

(Miller et al., Animal Cognition, 2019)

(Miller et al., Animal Cognition, 2019)

Two treats are then placed on the tray - one immediately available, and a better one that becomes available when the tray rotates after a short time. The better treat can either be of higher quality (meat instead of a piece of apple, for instance) or higher quantity.

For children in this study, the rewards were not actually edible - the kids got stickers, with larger, glittery stickers used for the higher quality reward.

Nine wild-caught crows and 61 children aged between three and five years were trained in how the apparatus works, and then tested with two conditions - with the rewards visible, and with one or both of the rewards hidden under a cover on the tray.

When the rewards were visible, both children and crows were really good at delaying gratification for a better treat - and, notably, they were much more willing to wait when the treat was better quality than when there was just more of the same.

This demonstrated in crows that they were willing to wait because they wanted the better snack, and not out of hunger.

But when it came to hidden treats, the human children performed better than the crows. It's unclear exactly why this may be, but it may have something to do with the crows' wildness, the researchers said.

Whenever the human scientist was in the aviary setting up the tray, the crows would stay away, and only approach the tray after the human was gone. Thus, they didn't know what reward was hidden under the cover, and had to rely on inference to figure out whether the hidden reward was worth waiting for.

The children, however, had no such fear, and were able to observe the scientist placing the stickers and remember what was under the cover.

"It is possible that this testing context, where the crows were also required to make decisions about taking an immediate or delayed reward varying in quality or quantity, as well as either hand tracking and/or reasoning by exclusion, resulted in a mental overload of working memory capacity and/or attentional allocation," the researchers wrote in their paper.

However, the results are consistent with an earlier 2014 study that was also based on the marshmallow test. New Caledonian crows were given a snack, and trained that if they waited, they'd be given a better snack, either in quality or quantity. In this test, too, the birds showed that they were more willing to wait for a better delicacy than a larger quantity of an inferior snack.

Yet another experiment conducted in 2014 showed that New Caledonian crows can understand cause and effect as well as a child can. When presented with a water displacement test - a series of tubes of water, and a treat floating out of reach - crows were able to place objects in the water to raise the level and reach the treat. This understanding was on a par with seven-year-old children, the researchers on that study said.

So it's possible, if the crows were able to learn hand-tracking and observe the human placing the treat, they would be able to perform just as well as children on the hidden treat test too.

"These results contribute to our understanding of self-control in birds and humans, and particularly, to some of the contextual factors that may influence performance in these tasks," the researchers wrote in their paper.

"These factors should be taken into account when designing future experiments and when comparing performance between different species. Hence, our findings help to provide a base for future research into the mechanisms of self-control."

The research has been published in Animal Cognition.