Tracking your steps each day can be a useful barometer of physical activity, but health recommendations based solely on step counts might miss some important nuance.

A new study of more than 33,000 adults in the UK Biobank suggests that how you space out your daily steps may affect your future health outcomes.

In the analysis, people who took most of their daily steps during longer strolls had a lower risk of dying from any cause than those who took most of their steps in shorter strolls.

Related: Study Reveals The Optimal Number of Daily Steps to Offset Sitting Down

Participants who walked for longer bouts also had a lower risk of a future cardiovascular event, like a heart attack or stroke, and that was true even after adjusting for the total number of steps taken.

"There is a perception that health professionals have recommended walking 10,000 steps a day is the goal, but this isn't necessary," says co-lead author Matthew Ahmadi, a public health researcher at the University of Sydney.

"Simply adding one or two longer walks per day, each lasting at least 10-15 minutes at a comfortable but steady pace, may have significant benefits – especially for people who don't walk much."

The sweeping analysis included adults aged 40 to 79 years who did not have cardiovascular disease or cancer and who typically walked fewer than 8,000 steps a day.

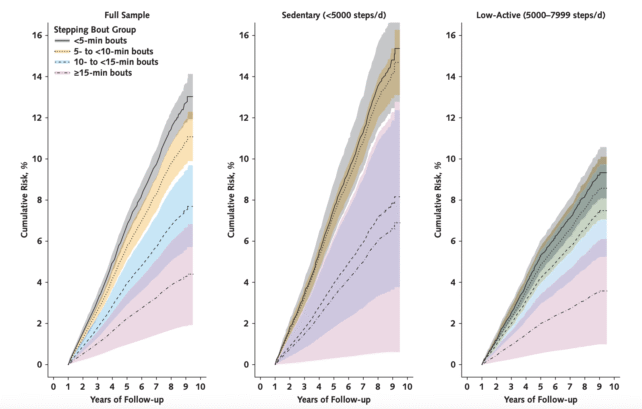

For a week, participants wore a fitness tracker to measure their steps. Looking back at those results, researchers found that those who took most of their daily steps in 10 to 15 minute chunks had a roughly 4 percent chance of experiencing a cardiovascular-related event, such as a heart attack or stroke, within the following decade.

Meanwhile, those who took most of their steps in spurts shorter than 5 minutes had about a 9 percent higher risk of suffering a future cardiovascular incident.

What's more, for those who took longer walks, the risk of dying was less than 1 percent, compared with roughly 4 percent for those who walked for shorter bouts.

The associated benefits were particularly notable among the most physically inactive participants, who walked fewer than 5,000 steps a day. Among this group, longer bouts of walking were associated with up to 85 percent lower mortality compared with shorter walks.

As compelling as the figures seem, the findings are only observational and are derived from just three days to a week of physical activity data, so they should be interpreted with caution.

That said, the sample size is large, and the idea that time spent exercising can impact health outcomes is supported by other recent studies.

It should also be noted that some of these studies have found the opposite association: that shorter, faster bouts of walking or better than longer, slower strolls.

The pace of walking was not fully assessed in the recent UK Biobank analysis, but it suggests that the total number of daily steps is not the only factor to consider.

Cardiologists Fabian Sanchis-Gomar from Stanford University, Carl Lavie from John Ochsner Heart and Vascular Institute in New Orleans, and Maciej Banach, from Medical University of Lodz in Poland speculate that longer bouts of continuous walking may promote cardiometabolic benefits, boost blood flow, or improve insulin sensitivity, effects that are "less likely to arise from brief, intermittent activity."

The editorial's writers, who weren't associated with the study, argue the investigation's authors make a "compelling case" for testing sustained walking in future randomized clinical trials.

Applied statistician Kevin McConway, who was also not involved in the study, agrees the paper is "intriguing" but argues we need far more research to test these results before they inform future recommendations for heart health.

"It's too early to tell how, if at all, these new findings should feed into public health recommendations on physical activity and step counting," McConway says.

Related: Powerful New Antibiotic Was 'Hiding in Plain Sight' For Decades

University of Sydney sports scientist and study author Emmanuel Stamatakis says that until now, the emphasis has largely been on the number of daily steps or the amount of walking people do, neglecting 'how' people walk.

"This study shows that even people who are very physically inactive can maximize their heart health benefit by tweaking their walking patterns to walk for longer at a time, ideally for at least 10 to 15 minutes, when possible."

The study was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.