In an ironic twist, researchers have just discovered that a tissue-damaging disease somehow has the potential to regenerate mammalian livers.

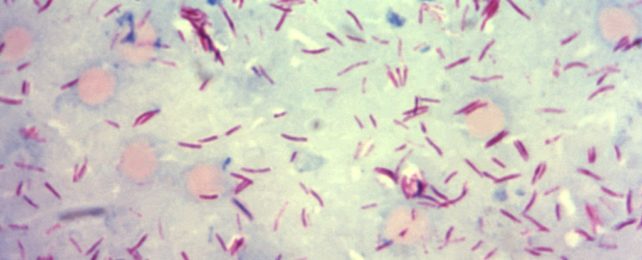

Leprosy, one of humanity's oldest and most persistent diseases, is caused by two parasitic bacteria, Mycobacterium leprae or Mycobacterium lepromatosis. These microbes damage skin, nerves, and other tissues during their infection.

Contrary to the stigma surrounding it, leprosy is not very contagious. It spreads through repeated and excessive contact with an infected person's mucus; however, 95 percent of those exposed to the bacteria do not end up with the disease, and it can be cured with a cocktail of modern drugs.

The bacteria occur naturally in armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus), and in studying the interaction between the microbe and its host, researchers noticed the parasite has an unexpected ability to hijack and reprogram cells.

So University of Edinburgh medical researcher Samuel Hess and colleagues infected 45 armadillos with M. leprae, 13 of which resisted infection, and they then compared the infected livers to a group of 12 animals that were not infected.

Amazingly, infected armadillos' grew more liver – their organs became perfectly supersized. The organs still remained functionally normal with all the correct types of liver tissues in all the right places, including proportionally expanded blood and bile duct systems.

"If we can identify how bacteria grow the liver as a functional organ without causing adverse effects in living animals, we may be able to translate that knowledge to develop safer therapeutic interventions to rejuvenate aging livers and to regenerate damaged tissues," explains University of Edinburgh cell biologist Anura Rambukkana.

It appears that over evolutionary history, the bacteria have learned to regenerate and increase the number of cells that best suit them within the armadillo's body where they live.

While the specifics are unclear, M. leprae seems to be reprogramming adult liver cells, hepatocytes, by converting them into a stem-cell-like state, allowing all the extra liver tissues to grow correctly from them.

Members of the research team previously demonstrated leprosy could do something similar to nerve support cells called Schwann cells, reprogramming them into a younger cell state that can produce a greater variety of cell types.

In the latest study of armadillos, this resulted in a perfectly healthy supersized liver with no signs of scarring, aging, fibrosis, or tumor.

"Thus regenerative medicine's pursuit of a "grown-to-order" functional organ is not theoretical but has a naturally occurring precedent," Hess and colleagues write.

While human livers do have the capacity to regrow at least in part – the only internal organ that can do so – even with repeated inflammatory injury of chronic liver disease, they accumulate damage over time, leaving millions of people succumbing to chronic liver diseases each year.

Understanding how leprosy parasites regenerate liver tissue may one day give us the power to harness this ability too.

"Although unexpected and unconventional, this evolutionarily refined in vivo [within body] model may advance our understanding of the native regenerative machinery," the team concluded in their paper.

This research was published in Cell Reports Medicine.