More than four centuries ago, the Capuchin Monastery (or Catacombe dei Cappuccini) in Palermo, Sicily, ran out of room in its little garden cemetery, so the monks spent many years excavating catacombs below the building for extra storage. The first body to be placed down there was brother Silvestro of Gubbio, who was mummified in 1599, washed in vinegar and put back in his robes.

While for the first couple of centuries, these catacombs were reserved exclusively for deceased monks, eventually they became open to every dead person - of a certain status. The elite few who found a place in the subterranean tombs would often stipulate in their wills which outfits they'd be displayed in, and whether or not these clothes be updated on a regular basis. The upkeep of the catacombs was funded by relatives concerned about keeping the remains of their loved ones pristine.

Right up until a famous little girl mummy - who appears to blink on a regular basis - was placed in the catacombs during the 1920s, the four, long limestone corridors were gradually filled with several thousand clothed mummies, some posed, some hung up from hooks by their necks.

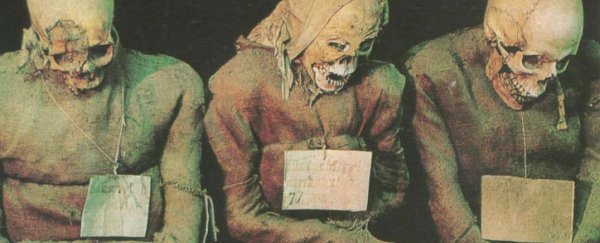

Separated according to their occupation in life, social status, gender and age, these "dehydrated dead" appear as priest mummies in their robes, military officer mummies in their uniforms, the social elite in their best suits and ball gowns.

"Dozens of long-dead infants, still in their baby clothes and many still in their cribs, keep each other company," says Bob Brier, an Egyptologist at Long Island University in the US, in a 2003 issue of Archaeology. "Suspended from their hooks, lawyers and physicians congregate in the hall of professionals. Normally one thinks of death as the great equaliser; not so in the catacombs of Palermo. Here class still has its privileges, a kind of Club Dead."

Many of the mummies have lost the lower parts of their noses, some have had their necks or mouths twisted grotesquely, their sunken eye cavities positioned to direct their gaze in certain ways. Jaws have been loosely wired to give many an unnatural gaping expression, as if they were screaming.

Having not accepted anyone's well-to-do relatives for almost a century, the catacombs have now become a paid tourist attraction for the morbidly curious. Brier described his rather unnerving visit:

"During a recent visit, I found myself wondering what it was about these mummies that made them so eerie. Perhaps it was their clothes and upright postures. We have always had separate realms for the living and the dead. Call it heaven, the netherworld, or just the graveyard, there's a place where the dead belong and it's not among the living, all dressed up for a day's work or an evening out. The Palermo mummies are ghoulish because they are not doing what they are supposed to be doing - they play at being alive."

According to A. A. Gill at National Geographic, in Europe, the people of Sicily have had a particularly strong relationship with the practice of desiccating and preserving the corpses of their loved ones. But no one really knows why.

Gill suggests that the mummification process was discovered by accident, and then a system was devised to get the best results. "The newly dead were laid in chambers, called strainers, on terracotta slats over drains, where their body fluids could seep away and the corpses slowly desiccate, like prosciutto," he writes. "After eight months to a year, they'd be washed with vinegar, put back in their best clothes, and either placed in coffins or hung on the walls."

Perhaps, says Gill, the practice was part of an old religious belief in the shamanistic powers of the dead - some corpses rotted away, despite efforts to preserve them, and others would remain the same for centuries, perhaps as an indication of such power. Perhaps they served as reminders to the community that material possessions are just that, and that wealth stored on Earth will remain right where it is after death. Perhaps, like macabre living-dead dolls, preserved by God, they served to reinforce faith.

We'll probably never know how and why the Palermo mummy collection came to be, as Gill writes for National Geographic, "They remain one of Sicily's many mysteries."

Here are some more pictures of the Capuchin mummies:

Gandolfo Cannatella / Shutterstock.com

Gandolfo Cannatella / Shutterstock.com

Gandolfo Cannatella / Shutterstock.com

Gandolfo Cannatella / Shutterstock.com

Sources: Archaeology, National Geographic