New antiviral drugs that promise a cure for the millions of Americans with chronic hepatitis are also benefiting another category of patients: those awaiting organ transplants.

Those patients can now receive an organ that has tested positive for hepatitis C, and if they become infected, they can be administered the antivirals to rid them of the disease.

The cost of the antivirals has dropped since their introduction, although at a low of US$26,400 for an eight-week course of treatment, they remain expensive.

For that reason, many state Medicaid agencies and some commercial insurers have restricted access to the medication, though a number of them are modifying the restrictions.

Transplant specialists say the availability of organs from donors with hepatitis C is easing the chronic shortage of organs.

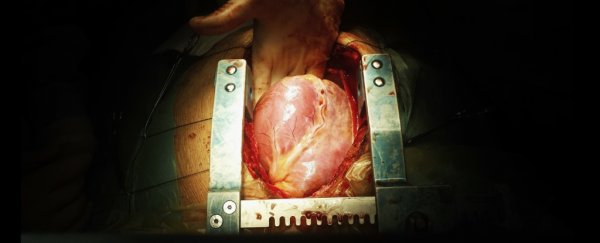

"I am not aware of any other development that has allowed us to expand the donor pool in this way," said Kelly Schlendorf, medical director of the adult heart transplant program at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, which started using hearts infected with hepatitis C in 2016 after successful transplants of infected livers at the Nashville hospital.

"We've been able to transplant 50 more hearts into patients on the waiting list," Schlendorf said.

"That's 50 hearts that wouldn't have been used before."

It is too early to know exactly how many more organs might eventually become available as a result of new policies regarding organs infected with hepatitis C, said David Klassen, chief medical officer of the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), the nonprofit that runs the nation's transplant system.

The use of those organs is still being tested, as transplant centers and organ procurement centers develop protocols and most potential donors don't yet know about these new standards.

But transplants of hepatitis C-infected organs have increased dramatically. In 2013, 482 hepatitis C-positive organs were used in transplants, according to UNOS data. By last year, 1,491 of the 37,795 organs used in transplants had tested positive for hepatitis C.

And in the first five months of 2018, the number had already reached 803.

"If you increase donations by 10 percent overall, you've made a hell of an impact," said Christopher Sciortino, surgical director of the Advanced Heart Failure Center at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and the lead investigator into the use of hepatitis C-infected hearts in transplantation.

"This is going to have the biggest impact we've seen in decades."

In a grim irony, the increase in organs available for transplants is caused in part by the opioid epidemic engulfing the United States.

Heroin addicts often share needles, contributing to the 400 percent increase in acute hepatitis C among 18-to-29-year-olds from 2004 to 2014, according to the Centers for Disease

Control and Prevention. Among those ages 30 to 39, the uptick was 325 percent.

"A little less than 15 percent of our donations are the result of the epidemic," said Kevin Cmunt, head of Gift of Hope, an organ procurement agency covering parts of Illinois and Indiana.

In 2016, an estimated 42,000 people died of opioid overdoses in the United States. Those two data points - the sharp increase in hepatitis C and the surge of opioid deaths - suggest that many more organs may be available for transplants.

"For all the damage [the opioid epidemic] has caused, the potential benefit is organ donation," said Michael Chang, head of gastroenterology and hepatology at the Veterans Affairs Portland Health Care System in Oregon.

UNOS manages the national transplant waiting lists and evaluates donors and recipients based on compatibility and need.

Geography also plays a major role, because organs have limited viability after the donor's death, ranging from four to six hours for hearts and lungs to 24 to 36 hours for kidneys.

The shortage for all is severe. In 2017, 34,770 organ transplants were performed in the United States. The number of patients on the waiting listfor organs is more than 114,000.

The biggest demand by far is for kidneys, followed by the liver, the heart, the pancreas, lungs and intestines.

"The long and short of it is the big limitation in getting patients transplants is the availability of donors," Sciortino said.

He recalled one woman in his hospital who waited three months for a heart before a hepatitis C heart became available.

"Before, that heart wouldn't have been used at all. Now - she's doing great."

The CDC estimates that 3.5 million people in the United States have hepatitis C, meaning they have been exposed to the virus and are producing antibodies to fight it.

Not everyone with hepatitis C antibodies will go on to develop the virus, and between 15 and 20 percent will clear the virus without needing treatment.

The rest are considered to have chronic hepatitis C, putting them at risk for developing an active virus that, left untreated, can cause cirrhosis and liver cancer and impair the kidneys.

The CDC says that hepatitis C kills more Americans than any other infectious disease.

Decades ago, people testing positive for hepatitis C were not automatically rejected as organ donors under the theory that it could take years, even decades, for the virus to develop.

Compared with the immediate perils of a failing organ, the risk seemed worth it.

But according to Klassen, use of hepatitis C-infected organs fell out of favor, and the practice all but stopped. An exception was made for recipients who already had tested positive for hepatitis C.

Before 2014, there were treatments for hepatitis C, but they had harsh side effects and their cure rate was no better than 45 percent.

But in 2013, drugmakers received federal approval for a new generation of direct-acting antiviral medications that boasted cure rates above 95 percent, virtually no side effects and a 12-week treatment period.

This is compared with older drugs that could take up to a year. However, the new drugs came with jaw-dropping price tags - as much as US$168,000 for a full course of treatment.

The price rattled insurers and prompted sharp criticism from patients and public officials. Medicaid agencies restricted who could receive the new drugs, reserving them for patients considered the sickest and those abstaining from alcohol.

They also limited prescribing privileges to certain medical specialties.

With more competition, the price of antivirals has dropped. Many Medicaid agencies lowered their requirements for how sick a patient had to be (measured by liver damage), and at least 17 dropped the requirement altogether.

At least two states, California and Oregon, have removed restrictions for Medicaid patients who have undergone transplants. Few commercial insurers have similar guarantees.

Several transplant physicians around the country said that if insurers have refused to pay for the antivirals, their hospitals have covered the expenses themselves, sometimes with the help of donations.

But payment remains a concern for transplant centers. Some automatically provide hepatitis C treatment for transplant patients who received an infected organ. Others wait for signs that the transplanted patient is developing the virus.

"Every center feels strongly that they need to be able to guarantee treatment" for hepatitis C, said Emily Blumberg, director of the transplant infectious-diseases program at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania.

Spending the money is good public policy, Vanderbilt's Schlendorf said.

"What needs to be considered is the cost of not getting a transplant quickly. It means more days in the[intensive care unit] waiting and more time on a heart pump. Those are more expensive than a course of hep C medicine."

2018 © The Washington Post

This article was originally published by The Washington Post.