More than a decade after mysterious holes were first discovered in the permafrost of Western Siberia, scientists are still putting forward new theories – from gas explosions to meteor impacts – on how they are formed.

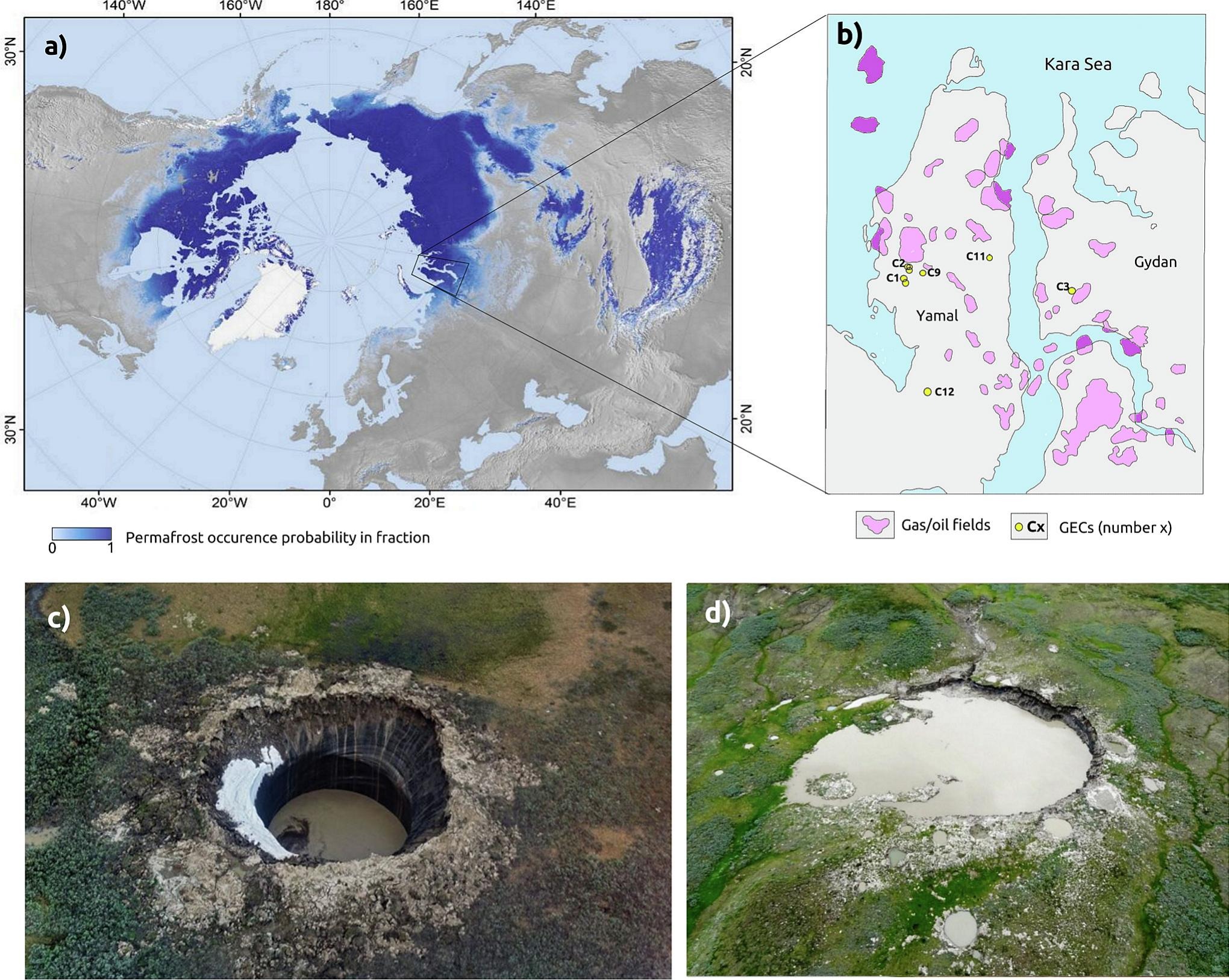

A team of geoscientists from the University of Oslo, led by Helge Hellevang, has now thrown their hat into the icy ring, putting forth a new model that could explain why these holes formed exclusively on the Yamal and Gydan peninsulas and not in other Arctic permafrost regions.

The first was discovered in Siberia's Yamal Peninsula in 2014. It was about 30 meters (98.4 feet) across and more than 50 meters deep, surrounded by ejecta that hinted at explosive origins. These inexplicable holes have walls so vertical that you'd be forgiven for thinking machines had dug them.

Related: Mysterious Craters Appearing in Siberia Might Finally Be Explained

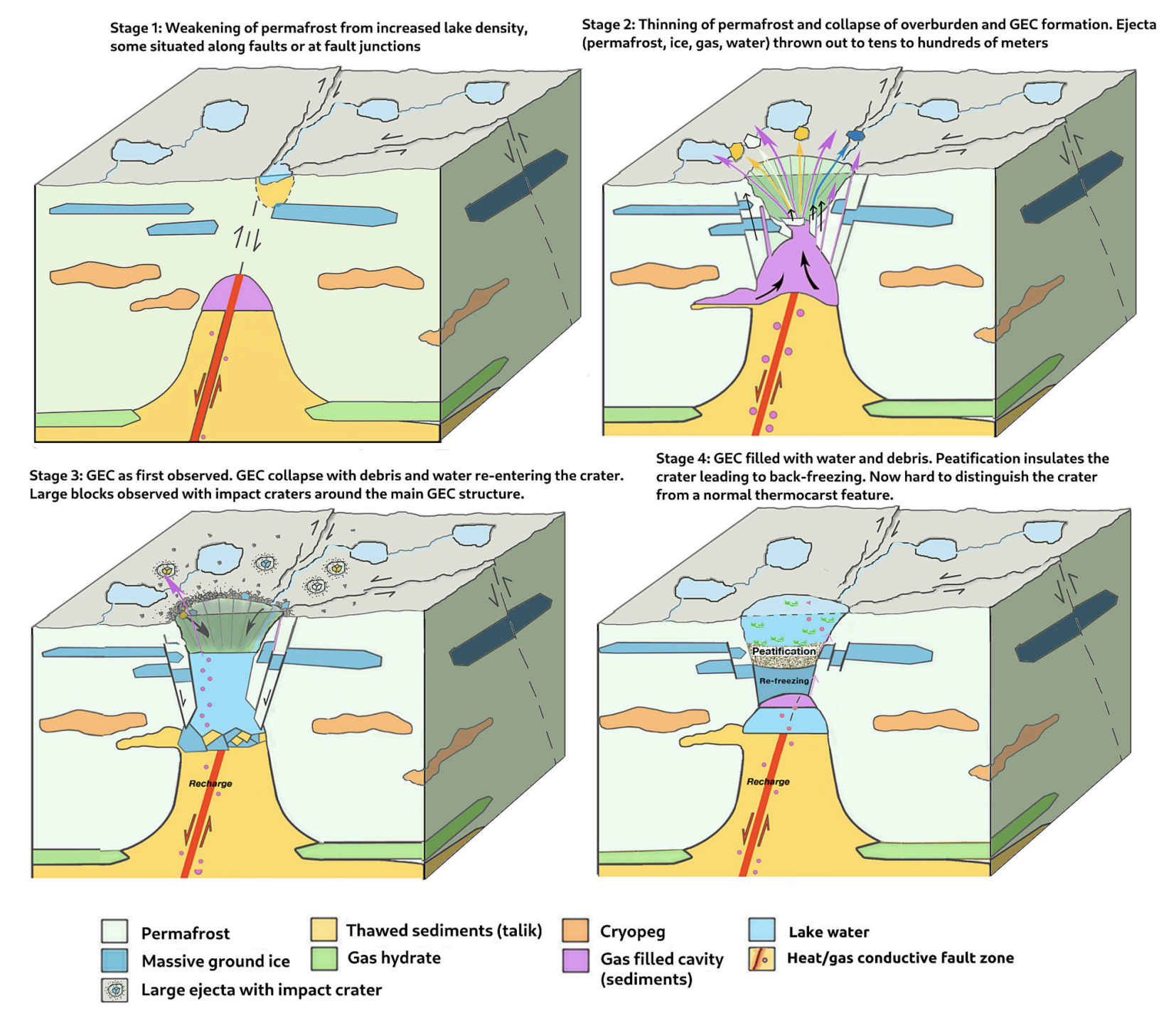

Hellevang and team agree that a buildup of pressurized methane is the driving force behind these holes, now referred to as gas emission craters (GECs). But while earlier models assumed that features of the permafrost itself were entirely responsible for the holes' formation, the new study found this unlikely.

"If permafrost-internal processes, triggered by climate change, were responsible for the eruptions, one would expect that GECs would also form elsewhere in areas of permafrost containing gas hydrates, ground ice, or cryopegs. This is not the case," Hellevang and team write.

"The volume of gas-filled cavities required to explain the GEC formation and ejecta is not likely to form by permafrost-internal processes alone."

Instead, they found that heat and natural gas from deep below the permafrost – the kind leaking from fault systems in the rock far below the Yamal and Gydan peninsula's ice – would be needed to create sufficient force for this subterranean explosion. This makes sense, given that these peninsulas are above one of the world's largest natural gas reserves.

They still maintain climate change plays a role: it may be the reason these holes become fully exposed, with growing lakes weakening the permafrost and creating a much thinner 'lid' for gas to burst through.

While this model gives a good explanation for the craters, it still needs to be tested against real-world measurements. Perhaps then we will truly get to the bottom of these craters.

This research was published in Science of the Total Environment.