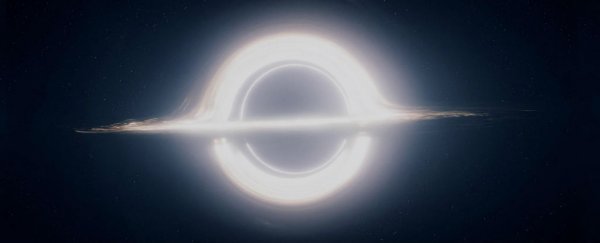

If you Google image search "black hole", you're going to be swimming in incredibly beautiful, shocking, and awe-inspiring images that only hint at the magnitude of these unfathomable comic giants.

But the sad truth is they're all just pretty pictures representing our best assumptions about the nature of black holes, because even light itself can't escape once it's fallen past the event horizon. Add that to the fact that black holes are incredibly far away from Earth, and they're almost entirely invisible to us.

Fortunately, physicists aren't the kind to give up simply because they're lacking a few photons - a team from MIT and Harvard has developed a new algorithm that could help them produce the first actual image of a black hole.

"A black hole is very, very far away and very compact," lead researcher and graduate student at MIT, Katie Bouman, explains. "[Taking a picture of the black hole in the centre of the Milky Way galaxy is] equivalent to taking an image of a grapefruit on the Moon, but with a radio telescope."

"To image something this small means that we would need a telescope with a 10,000-kilometre diameter, which is not practical, because the diameter of Earth is not even 13,000 kilometres."

Just take a second to let that sink in. We need a telescope bigger than EARTH to see these things the way we see other planets and stars… It's clearly time for Plan B.

Plan B is an algorithm that essentially stitches together data collected from radio telescopes positioned all around the globe to create a cohesive image of a black hole - a project known as the Event Horizon Telescope.

Why radio telescopes? Well, we know that black holes don't emit visible light like stars and asteroids do, but we could use radio wave signals to get an idea of what black holes look like, and these signals come with the added bonus of not getting jumbled up in space dust.

"Radio wavelengths come with a lot of advantages," says Bouman. "Just like how radio frequencies will go through walls, they pierce through galactic dust. We would never be able to see into the centre of our galaxy in visible wavelengths because there's too much stuff in between."

The drawback of using radio telescopes is that, because they have such long wavelengths, they require enormous antenna dishes, as Larry Hardesty explains for MIT News:

"The largest single radio-telescope dish in the world has a diameter of 1,000 feet [304 metres], but an image it produced of the Moon, for example, would be blurrier than the image seen through an ordinary backyard optical telescope."

Instead of building a radio telescope the size of Earth to see a black hole, we're going to turn Earth itself into a giant radio telescope dish, by linking up as many radio telescopes as we can, and then filling in the knowledge gaps with a lot of very clever maths. Science, ILU.

Bouman and her team have so far gotten six observatories from around the world to sign on to the Event Horizon Telescope project, and they expect to get confirmations from more in the coming weeks.

The plan is for these telescopes to train in on the black hole at the centre of our Milky Way galaxy, called Sagittarius A, filtering out as much 'noise' as possible. Using the data they collect, Bouman and her team will start to construct the first direct image of a black hole.

At the same time, Bouman's new algorithm, called CHIRP (Continuous High-resolution Image Reconstruction using Patch priors), will be applied to the data being shared across the telescopes, making an informed 'guess' in places that the telescopes can't access.

It does this using the same technique physicists have used to detect black holes in our galaxy, and beyond.

"To detect black holes today, computer-powered observatories scan for and record bright points of light that are emitted as a black hole, say, eats a star's plasma," Sarah Kramer explains for Tech Insider.

"The new model will take such data about known black holes to identify common patterns among the enigmatic objects. Then the software will 'learn' those patterns and use them to predict what appears in areas we can't see using radio telescopes."

The team is expected to present their plan on June 27, at the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition in Las Vegas. From that point, other researchers will have the chance to pore over their calculations and figure out how sound it all is, and if their assumptions are correct, we just might see the first ever direct image of black hole some time next year.

We seriously cannot wait.