Thanks to newly found fossilised poop, researchers have a better understanding of what ancient ground sloths ate on a daily basis - and let's just say, it was a little weird.

Based on their findings, on the menu for the sloths was an orange-flowered shrub called a desert globemallow (Sphaeralcea ambigua), a drought-tolerant plant called saltbush (Atriplex), and 'Mormon tea' (Ephedra) - a medicinal tea plant that humans have used to treat various ailments for over 60,000 years.

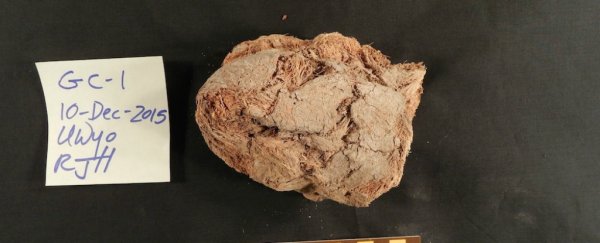

The poop samples (or 'coprolites') were found inside Gypsum cave in southern Nevada, where researchers say the extinct ground sloths used to call home some 11,000 to 36,000 years ago.

"Radiocarbon dates from the coprolites correlate with periods where the climate was a bit cooler, and since we know that modern tree sloths don't thermoregulate [regulate body temperature] very well, it's possible that these ground sloths were going into the cave to keep warm," one of the team, Ryan Haupt from the University of Wyoming, told Laura Geggel at Live Science.

These sloths weren't the diminutive things we're used to seeing today, either. Ancient ground sloths were humongous.

The Shasta ground sloth (Nothrotheriops shastensis) - the species that was probably responsible for the fossilised poop - weighed up to 250 kilograms (551 pounds), and could grow to about 2.75 metres (9 feet) in length.

The researchers only needed a tiny portion of the fossilised poop to analyse the creature's diet, checking the samples for certain carbon and nitrogen isotopes.

After gauging these isotopes, they were able to match them with specific plants by looking at how many stable heavy and light carbon isotopes were present.

This process is known as stable isotopic analysis, and it lets researchers look at molecular makeup of the samples in more detail than ever before.

Previous methods, which often involved piecing plant matter together from large coprolite samples like a jigsaw puzzle, relied on finding actual preserved samples of vegetation.

"In the past, there have been studies on these, but what they've had to do is literally take [the coprolites] apart, pull all of the little plant parts out and try to identify them one at a time," Timothy Gaudin from the University of Tennessee, who was not involved in the study, told Live Science.

"And then you end up with no specimen."

Another added benefit of the new technique - besides saving a person from actually messing around with ancient poop all day - is that researchers can now match the molecular makeup of the coprolites to the molecular composition of the animal's bones.

In this case, they found that many of the molecules in the sloths' food were also present in their bones. Basically, sloths are what they eat on an atomic level.

The researchers used this bone data to cross-examine different sloth species from that era and today, to see if they had similar diets. They found that Shasta ground sloths were mixed feeders, compared to more modern species.

"No one has ever attempted this type of analysis before using sloth coprolites, so we were really excited to see how well it worked," Haupt said.

It's important to note that the team's work has yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal, so adjustments could be made to the final results once it undergoes the scrutiny of other researchers.

It was presented at the 2016 Society of Vertebrate Palaeontology meeting last week.

Oh, and just in case you're wondering, modern sloths go through hell every time they poop.

They only relive themselves once a week, and it all comes out in one go, making for a less-than-ideal movement through the bowel that actually puts them in real danger, because it's really the only time they ever come down from their trees.