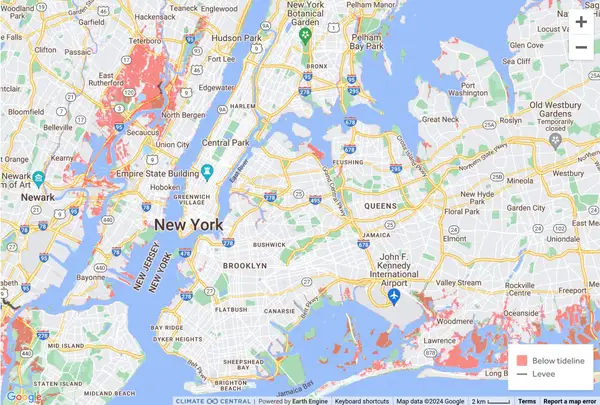

A couple feet of sea level rise may not sound like a lot. But if sea levels rose by two feet (0.6 meters) worldwide, the effects on coastal communities would be catastrophic.

Cities like New York, Miami, and New Orleans would experience devastating flooding. Across the globe, 97 million people would be in the path of rapidly encroaching waters, putting their homes, communities, and livelihoods at risk.

That's what would happen if the Thwaites glacier, nicknamed the 'doomsday glacier,' collapsed. But it wouldn't stop there.

Right now, this massive Antarctic ice shelf blocks warming sea waters from reaching other glaciers. If the Thwaites collapsed, it would trigger a cascade of melting that could raise sea levels another 10 feet (three meters).

Already, the melting Thwaites contributes to 4 percent of global sea level rise. Since 2000, the Thwaites has lost over 1,000 billion tons of ice. But it's far from the only glacier in trouble, and we're running out of time to save them.

That's why geoengineers are innovating technologies that could slow glacial melting.

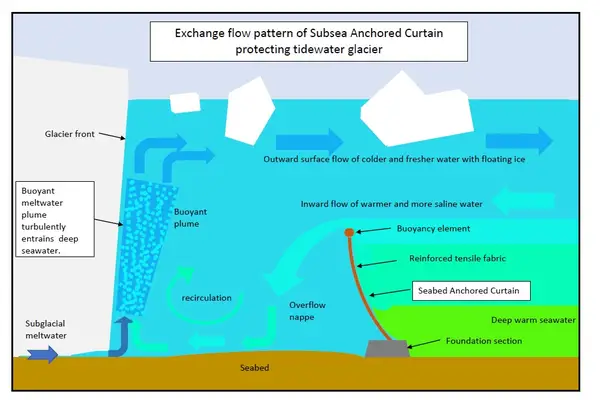

The latest strategy is curtains. That's right — underwater curtains. John Moore, a glaciologist and geoengineering researcher at the University of Lapland, wants to install gigantic 62-mile-long underwater curtains to prevent warm seawater from reaching and melting glaciers.

But he needs $50 billion to make it happen.

Drawing the curtains on glacial melting

One of the main drivers of glacial melting is the flow of warm, salty sea water deep within the ocean. These warm currents lap against the sides of the Thwaites, for example, melting away the thick ice that keeps the shelf's edge from collapsing.

As oceans warm due to climate change, these intruding currents will increasingly erode the Thwaites, driving it closer to total collapse.

Moore and his colleagues are trying to figure out if they could anchor curtains on the Amundsen seafloor to slow the melting.

In theory, these curtains would block the flow of warm currents to the Thwaites to halt melting and give its ice shelf time to re-thicken.

-

This diagram shows how a seabed anchored curtain could block the deep warm water currents from reaching glaciers. (Arctic Centre / University of Lapland)

This isn't the first time Moore has suggested this blocking solution. His curtain idea is based on a similar solution he proposed back in 2018, which would block warm water using a massive wall.

But curtains are a much safer option, according to Moore.

They're just as effective at blocking warm currents, but much easier to remove if necessary, he explained.

For instance, if the curtains took an unexpected toll on the local environment, they could be taken out and redesigned.

"Any intervention should be something that you can revert if you have second thoughts," Moore said.

While Moore and his colleagues are still decades away from implementing this technology to save the Thwaites, they are in the middle of testing prototypes on a smaller scale.

A $50 billion idea

Moore's colleagues at the University of Cambridge are already in the very early stages of developing and testing a prototype, and they could progress to the next stage as early as summer 2025, according to Moore.

Right now, researchers at the University of Cambridge are testing a 3-foot-long version of this technology inside tanks. Once they've proven its functionality, they'll move on to testing it in the River Cam, either by installing it at the bottom of the river or by pulling it behind a boat, Moore said.

The idea is to gradually scale up the prototypes until evidence suggests the technology is stable enough to install in the Antarctic, Moore explained.

If all goes well, they could be testing a set of 33-foot-long curtain prototypes in a Norwegian fjord in about two years.

"We want to know, what could possibly go wrong? And if there's no solution for it, then in the end you just have to give up," Moore said. "But there's also a lot of incentive to try and make it work."

With scaling comes an increased need for funding. This year's experiments will cost around $10,000. But to get to the point where Moore and his colleagues could confidently implement this technology, they'll need about $10 million.

And they would need another $50 billion to actually install curtains in the Amundsen Sea.

"It sounds like a hell of a lot," Moore said. "But compare the risk-risk: the cost of sea level protection around the world, just coastal defenses, is expected to be about $50 billion per year per meter of sea level rise."

-

This map shows the amount of area in and around New York City that would become submerged if sea levels rose three feet (in red). (Climate Central / Google Earth Engine)

While some coastal cities, like New York, have the budget to adapt to rising seas, others won't even come close.

"One of the great driving forces for us is this social justice point — that it's a much more equitable way of dealing with sea level rise than just saying, 'We should be spending this money on adaptation,'" Moore said.

A race against time

Data shows that the Thwaites glacier, and others like it, are melting at unprecedented rates due to climate change. But the question of when they could collapse remains up for debate among glaciologists.

"We really don't know if [the Thwaites] could collapse tomorrow, or 10 years from now, or 50 years from now," said Moore, adding, "We need to collect better data."

But collecting better data will take time that these glaciers might not have.

Proponents of glacial geoengineering, like Moore, believe that the time for intervention is now. Other experts disagree, arguing that cutting carbon emissions is the only viable way to slow glacial melting.

While reducing emissions is essential for mitigating the effects of climate change, Moore isn't confident that we'll cut back drastically or quickly enough to save the Thwaites. Once it reaches a tipping point, "Then the glacier doesn't really care anymore about what humans want to do about their emissions," he said.

"At that point, that's when you need these other tools in the box."

This article was originally published by Business Insider.

More from Business Insider: