Clouds of electrons blooming in deep space have been revealed in a whole new level of detail, showing cosmic phenomena unlike anything astronomers have seen before.

Resembling eerie dancing ghosts in space, these colossal specters could reveal new information about the behavior of supermassive black holes – and the complex environment between galaxies.

They are, astronomers discovered, being produced by winds from two active supermassive black holes at a distance of about a billion light-years. They have been named PKS 2130-538, and much about them remains mysterious.

While the 'ghosts' and the two radio galaxies thought responsible for their formation have been seen before, no previous observations have captured them in such glory.

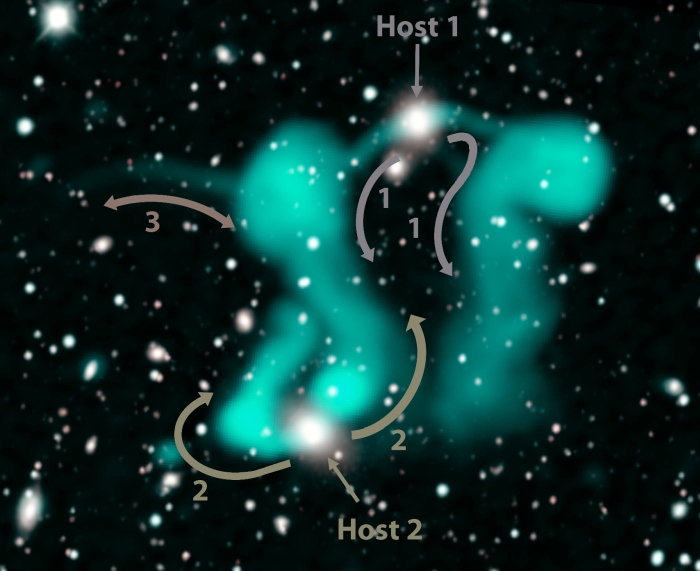

The ghosts, and the galaxies making them. (Norris et al., arXiv, 2021)

The ghosts, and the galaxies making them. (Norris et al., arXiv, 2021)

"When we first saw the 'dancing ghosts' we had no idea what they were," explained astrophysicist Ray Norris of Western Sydney University and CSIRO in Australia.

"After weeks of work, we figured out we were seeing two 'host' galaxies, about a billion light-years away. In their centers are two supermassive black holes, squirting out jets of electrons that are then bent into grotesque shapes by an intergalactic wind.

"New discoveries however always raise new questions and this one is no different. We still don't know where the wind is coming from? Why is it so tangled? And what is causing the streams of radio emission? It will probably take many more observations and modelling before we understand any of these things."

The peculiar objects were just one in a trove made by the Australian Square Kilometer Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) radio telescope array, as part of its Pilot Survey of the EMU (Evolutionary Map of the Universe) survey.

One of the most sensitive radio telescopes ever built, and the world's fastest survey radio telescope, ASKAP is designed to see deep into the radio Universe and reveal secrets we had no idea were out there.

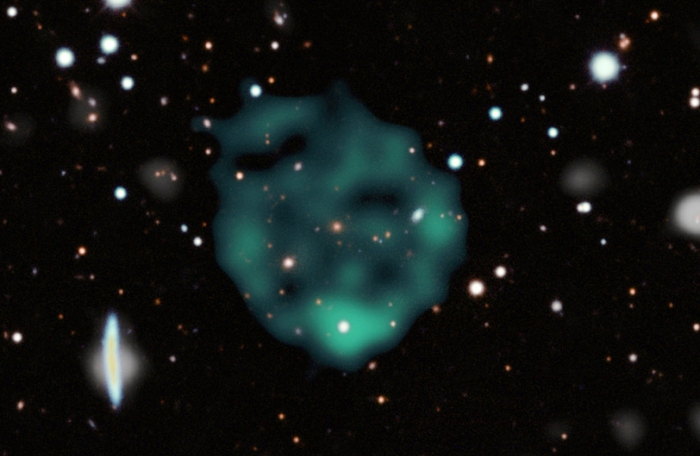

Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No – it's an ORC! (Norris et al., arXiv, 2021)

Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No – it's an ORC! (Norris et al., arXiv, 2021)

That's exactly what it's doing. Last year, the survey revealed the presence of what have been called Odd Radio Circles, or ORCs, which seem to be giant circles of radio emission a million light-years across, surrounding distant galaxies. We still don't know what they are.

To date, the EMU pilot survey has amassed a catalogue of around 220,000 sources of various sorts, many of which had never even been suspected.

"We are even finding surprises in places we thought we understood," Norris said.

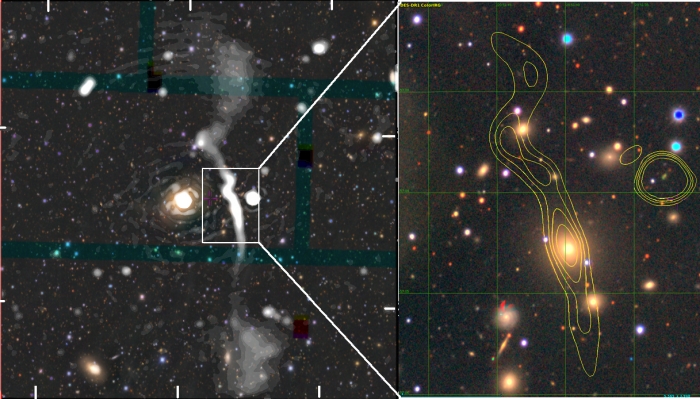

"Next door to the well-studied galaxy IC5063, we found a giant radio galaxy, one of the largest known, whose existence had never even been suspected. Its supermassive black hole is generating jets of electrons nearly 5 million light-years long. ASKAP is the only telescope in the world that can see the total extent of this faint emission."

Giant, previously invisible galaxy plumes. (Norris et al., arXiv, 2021)

Giant, previously invisible galaxy plumes. (Norris et al., arXiv, 2021)

Most known radio sources are from active supermassive black holes in the centers of galaxies. This is because as these black holes devour matter, material is funneled around the outside of the event horizon along magnetic field lines and blasted away from the poles in the form of radio-loud jets.

These sources are the brightest in the radio sky, and therefore that's what radio telescopes tend to pick up. ASKAP is starting to show us the extent of the radio Universe – those fainter sources that we don't usually see, such as synchrotron emission from radio relics in galaxy clusters, and more mysterious objects, like ORCs and dancing ghosts.

And this is just the pilot survey. The EMU survey is expected to continue for years, peering deep into the night to uncover the mysteries in the dark.

"We are getting used to surprises as we scan the skies as part of the EMU Project, and probe deeper into the Universe than any previous telescope," Norris said. "When you boldly go where no telescope has gone before, you are likely to make new discoveries."

You can visit the EMU Project website here, and zoom in to explore ASKAP's radio sky.

The team's paper cataloguing 180,000 compact radio sources has been accepted in Publications of the Astronomical Society of Australia, and is available on arXiv.