This year marks a once in a lifetime event in the mysterious world of periodical cicadas: the simultaneous emergence of two separate broods in the US, a rare phenomenon that last occurred in 1803.

One of the greatest enigmas of the insect world, periodical cicadas (Magicicada spp.) live up to 99.5 percent of their lives underground as nymphs, feeding on tree root sap. Some broods wait 13 years to become adults; others wait 17 years.

The dual emergence of these two broods in 2024 marks a rare occasion of their 13 and 17 year life cycles synchronizing. This exciting double event won't happen again until 2245.

Millions of cicadas from Brood XIII and XIX will emerge from the soil around mid-year to shed their exoskeletons as they transform from wingless nymphs into adults, leaving behind husks that may blanket trees and ground areas.

Then, life for the adult cicada is a whirlwind of mating and egg-laying.

The sheer number of cicadas singing loudly at a range of up to 90 decibels could be a bit of an earful, but these insects are otherwise harmless to humans and pets.

Males are responsible for the shockingly loud racket, serenading the silent females with species-specific mating songs created by vibratory structures on the sides of their abdomens, called tymbals.

After mating, females use a special tool called an ovipositor to make holes in small tree branches, depositing their precious egg cargo within. The adult cicadas will mate, lay eggs, and die all within a few weeks.

When the eggs hatch, the nymphs fall to the ground, burrow into the soil and begin the next 13 or 17 year cycle, spending nearly all their life underground.

No one knows for certain how or why the cicadas perform this precisely timed mass entry into the world above ground, but recent progress suggests that the Magicicada mystery may be solved within the next decade.

The numbers of these curious critters during their coordinated emergence are thought to be a defense against predators such as birds, wasps, and mantises. Flooding the ecosystem with more cicadas than predators can possibly eat at a time certainly increases their chances of avoiding them and finding a mate.

Predators could take advantage of this – and sync up their life cycle with that of the cicadas to ensure lots of food is available at breeding time – becoming a larger threat and perhaps preventing any cicadas escaping their fate as a meal.

But having such long drawn out life cycles appears to help periodical cicadas keep predators from synchronizing their breeding times. Having a seasonal breeding cycle based on a prime number (like 13 and 17) also helps them avoid predators with a life cycle that is a factor of those numbers.

For instance, any predator species with a 2, 3, 4, or 6-year life cycle could wipe out a 12-year cicada species because an increase in the predator population would coincide with each cicada emergence.

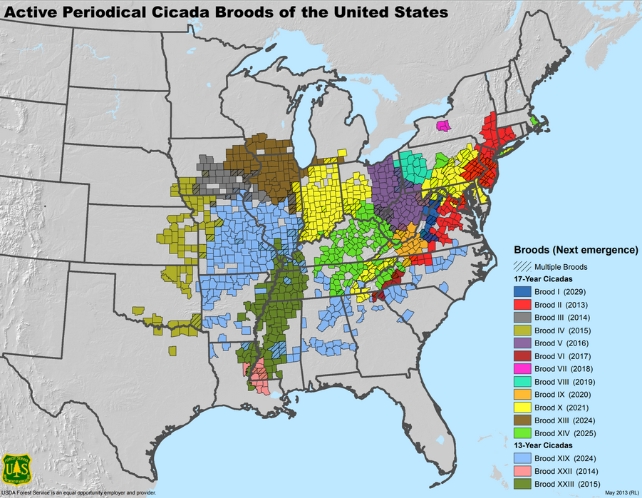

All periodical cicadas of the same life cycle type that share the same emergence year form a 'brood'.

Studying these broods can provide valuable insights into insect behavior, population dynamics, and the influence of cicada emergence on the ecosystem. Magicicada are among the most studied insects in evolution and ecology.

No other animal has a life cycle as lengthy, stable, and synchronized as this one, reproducing in large numbers and only once. Though one intriguing arthropod comes somewhat close; a Japanese millipede which explodes in numbers every 8 years.

Brood XIII (the Northern Illinois Brood) was last seen in 2007. This brood emerges every 17 years and inhabits the eastern US. You can expect to hear their buzzing across Wisconsin, and parts of Illinois and Indiana.

Brood XIX (the Great Southern Brood) last showed up in 2011 and primarily calls the southeastern US home. This 13-year cycle brood will emerge in multiple locations, including Tennessee, Georgia, Texas, and Alabama.

While the timing of their emergence can vary slightly depending on weather, both broods XIII and XIX are expected to appear above ground between May and June, when soil temperatures reach about 17.9 °C (64 °F).

A geographic overlap occurs mainly in Illinois, where along with some other areas, you might hear the combined songs of both broods.

You can expect to see and hear Magicicada everywhere, from your backyard to parks and even urban areas.