Over a decade ago, Bruce Walker was working at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) when he was asked to see a patient who claimed to be infected with the human immunodeficiency virus ( HIV) but who was entirely well, despite never taking any medication.

"Quite frankly," Walker, an immunologist and physician, recalls, "I actually didn't believe him."

But it turned out to be true, and not just for this one patient.

Years of recent research has come to show among 35 million people infected with HIV, there are a rare few who might be able to suppress the virus on their own without treatment, and they're known as 'elite controllers'.

Now, new research suggests an even rarer subset might actually rid themselves of the virus completely without any medical help.

Such a finding is remarkable because HIV is a lifelong condition with no medical cure, and it usually requires daily antiretroviral therapy (ART) to control the virus' replication and stop acquired immunodeficiency syndrome ( AIDS) from developing.

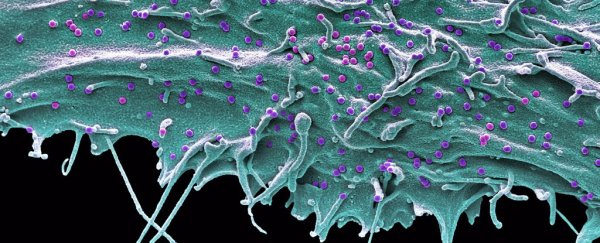

When HIV infects human cells, it inserts copies of its genetic material into the cell's genome, creating a viral reservoir for replication.

Antiviral drugs can usually keep replication of these reservoirs at bay, at least to some extent. But there are others who don't need these drugs at all.

Less than 0.5 percent of those infected with HIV appear to stop the virus being replicated all on their own, and we're still not sure why or how.

"What happens with these individuals, whom we call elite controllers, may shed light on an HIV-1 cure and also help us understand how a person with HIV might control virus and avoid HIV-associated comorbidities," says Keith Hoots a director if blood disease research at the National Institutes of Health and a veteran HIV researcher himself.

To that end, a collaboration between MGH, MIT and Harvard have gathered together over 1,500 confirmed cases of 'elite control'. After years of digging, their research has revealed results previously only known to have been achieved through rigorous medical treatment.

While there are currently two cases where HIV is said to have been 'cured' through bone marrow transplantations, the authors say elite controllers are the closest thing we have to a possible "natural cure".

Sequencing billions of cells from 64 HIV patients, who kept the virus at bay for a median of nine years without medication, and 41 individuals, who were taking ART for a median of nine years, the team found something astonishing.

Despite analysing billions of their personal cells, one patient showed absolutely no intact HIV copies, and another patient had only one intact copy that was "blocked and locked" in a sort of genomic straight jacket, which stops the virus from being replicated.

This raises the possibility that a 'sterilising cure' of HIV, in which the participant's immune system has removed all intact HIV genomes from the body, may be achieved naturally in extremely rare instances, according to the authors.

In a Nature review of the paper, immunologist Nicolas Chomont says it will be hard to demonstrate whether HIV has been completely eradicated in these two patients. That said, he admits, these cases are "certainly reminiscent of previous reports of HIV cure."

Even elite controllers who had more intact copies of the virus had them securely locked away.

Instead of being stored in active regions of the human genome, 45 percent of the viral reservoirs in elite controllers were discovered in 'gene deserts', where the patient's DNA nor the genetic sequence inserted by the virus is ever effectively expressed, leading to sustained, drug-free 'silencing' of the virus.

People on ARTs, on the other hand, kept only 17 percent of their viral reservoirs in these inactive regions, which means if they stop taking their medication, most viral copies will begin replicating again.

"This positioning of viral genomes in elite controllers," Yu says, "is highly atypical, as in the vast majority of people living with HIV-1, HIV is located in the active human genes where viruses can be readily produced."

It's not clear how these differences came to be, but when the authors infected the cells of elite controllers with HIV, the virus integrated into active genomic sites as per usual. So where did these copies in the elite controllers go?

Recent research indicates that T cells, which seek and destroy infections, might play a role in cleaning up the virus.

Far from integrating HIV at different genomic sites, the authors thus argue, it seems elite controllers can eliminate proviral sequences at active transcription sites, carefully watched by their immune systems.

"By contrast, less transcriptionally active proviral sequences with features of deep latency, leading to lower vulnerability to immune recognition, seem to persist long-term," they write.

This indicates our immune systems may have a way that researchers could use to target viral sequences at risk of being replicated. And while this doesn't change anything for HIV patients right now, it does suggest a possible avenue for future treatment.

Virologist Monica Roth from Rutgers University, who was not involved in the study told Science News the idea put forward in this paper is "intriguing" but that "there's no evidence saying that it happens" in reality.

Genomic research can only tell us so much, so we still need more research to understand how the immune systems of some people living with HIV can suppress the virus naturally.

The study was published in Nature.