An unusual whale feeding technique only recorded for the first time in 2011 may have been around for at least two thousand years, according to researchers from Flinders University in Australia.

Though whales have been seen feeding, breathing, and breaching the ocean surface for as long as humans have gazed at the sea, their depictions in our art and stories haven't always been true to nature.

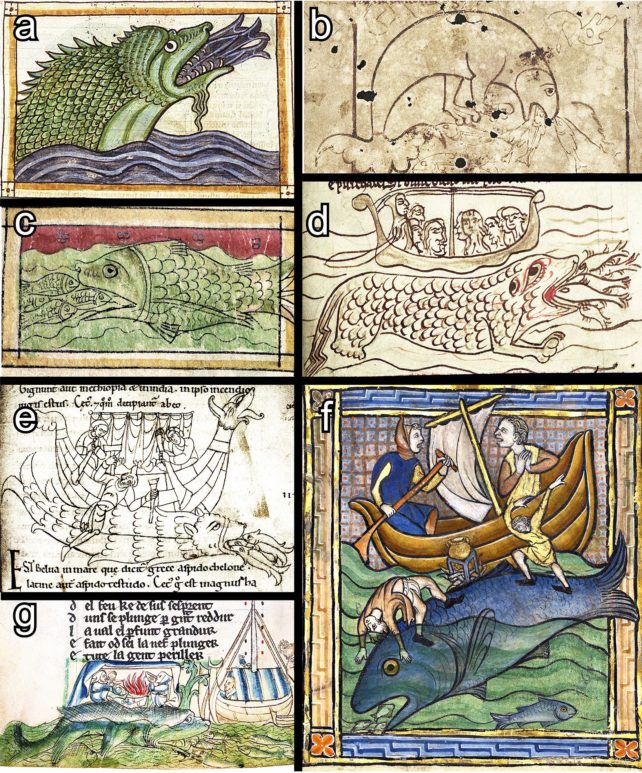

The ancient Greeks named one such ocean creature aspidochelone, or 'asp turtle', which featured giant spines and was reported to have been so large it could be mistaken for an island.

Old Norse manuscripts from the 13th century also featured a marine beast called a 'hafgufa', meaning 'sea steam' or 'sea mist'. In spite of its rather fantastical description, some of its behavior just might have been inspired by authentic observations of whales feeding.

According to a fresh evaluation by scientists, depictions of the creature could describe a stationary whale holding its giant mouth agape at the surface of the ocean.

"… the big fish keeps its mouth open for a time, no more or less wide than a large sound or fjord, and unknowing and unheeding, the fish rush in in their numbers," reads a translation of the Norwegian manuscript.

"And when its belly and mouth are full, [the hafgufa] closes its mouth, thus catching and hiding inside it all the prey that had come seeking food."

In this account and others like it, the size of hafgufa is no doubt exaggerated, but researchers say the beast's description is "otherwise strikingly similar" to a trap-feeding whale.

Trap-feeding is a rare sight for modern whale watchers. Scientists have only recently cataloged the passive hunting technique among humpback whales (Megaptera noveangliae) in the northeast Pacific and among Bryde's whales (Balaenoptera brydei) in the Gulf of Thailand. But there's a chance it was once used more widely by whale cultures in the past.

When a whale is trap-feeding, it does not swim but holds its lower jaw perpendicular to the surface of the ocean, still as can be, flush with the water line or sitting just below. In this way, the whale's mouth creates a sort of pool into which fish are drawn and become easily trapped. At the right moment, the whale snaps its mouth shut.

In modern drone footage, you can actually see fish flopping within the whale's yawning mouth, while seagulls swarm around the unmoving mass, as though it were an island.

"It struck me that the Norse description of the hafgufa was very similar to the behavior shown in videos of trap-feeding whales, but I thought it was just an interesting coincidence at first," recalls maritime archaeologist John McCarthy from Flinders University in Australia.

"Once I started looking into it in detail and discussing it with colleagues who specialize in medieval literature, we realized that the oldest versions of these myths do not describe sea monsters at all, but are explicit in describing a type of whale."

When McCarthy and his colleagues asked marine biologists for their opinion on the matter, what started as a hazy notion began to take shape as a fully-fledged hypothesis.

As it turns out, it's not just a whale's head that our ancestors might have mistaken for a sea monster, either. A mistaken glimpse of a whale's penis has been suggested as responsible for at least one sea-serpent sighting noted in history.

Unlike whale sex, however, which happens just about everywhere there are whales, trap-feeding seems to be uncommon.

It could be a culturally-learned whale behavior that is used only in areas where small fish hang out near the surface, or where fish density is too low to use high-energy strategies like lunge feeding, where the whale opens its mouth and charges at the school of fish.

Today, it is cataloged in only two whale species on opposite sides of the world. But there's a chance it was more common in the past.

"We found that the more fantastical accounts of this sea monster were relatively recent, dating to the 17th and 18th centuries, and there has been a lot of speculation amongst scientists about whether these accounts might have been provoked by natural phenomena, such as optical illusions or underwater volcanoes," says Erin Sebo, who researches medieval literature at Flinders.

"In fact, the behavior described in medieval texts, which seemed so unlikely, is simply whale behavior that we had not observed but medieval and ancient people had."

However mythical these ancient accounts might seem on the surface, scientists could still learn something from them today.

In a translation of a 2,000-year-old Greek text on aspidochelone, for instance, the mythical whale is said to exhale a 'good-smelling' odor that attracts smaller fish.

Whereas in the Norwegian manuscript cited earlier, the whale is said to expel its own bile as bait to draw the fishies in.

According to experts, humpbacks and Bryde's whales can both regurgitate during feeding. When these two whales eat, they are also said to smell of dimethyl sulfide, an odor we often associate with rotten cabbage.

"Although no test has been made of whether the release of this regurgitated material contributed to drawing more prey into a kill zone, many rorqual prey species such as herring and euphausiids (krill) are omnivorous and would undoubtedly be drawn to this ejecta," researchers write.

That's something that whale scientists will need to investigate further, although fish, turtles, and penguins are all known to be drawn to trap-feeding events.

"It's exciting because the question of how long whales have used this technique is key to understanding a range of behavioral and even evolutionary questions," says Sebo.

"Marine biologists had assumed there was no way of recovering this data but, using medieval manuscripts, we've been able to answer some of their questions."

The study was published in Marine Mammal Science.