A microscopic clump of sodium has become the largest object ever to be observed as a wave, improving upon previous records by thousands of atoms.

Quantum physics defines particles in terms of waves, which effectively means all matter exists in a muddle of many possible states at once – known as a superposition – before being measured.

Though most obvious on the sub-atomic scale of electrons and photons, all things, from atoms to humans to whole galaxies and beyond, exist in superpositions. In theory, at least. Observing this on ever-larger scales is challenging (if not potentially impossible).

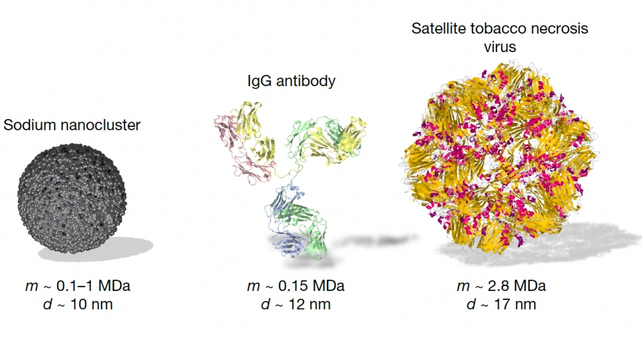

In a new study, researchers from the University of Vienna in Austria and the University of Duisburg-Essen in Germany report one of the largest objects observed in a superposition. The particle measured roughly 8 nanometers in diameter, and at more than 170,000 atomic mass units, was more massive than many proteins.

Their experiment shows that even nanoparticles of sodium, each with thousands of individual atoms, follow the rules of quantum mechanics, despite their relatively enormous size.

"Intuitively, one would expect such a large lump of metal to behave like a classical particle," says lead author Sebastian Pedalino, a graduate student at the University of Vienna.

"The fact that it still interferes shows that quantum mechanics is valid even on this scale and does not require alternative models."

The researchers sent the super-cooled particles through an interferometer that featured a series of diffraction gratings generated by ultraviolet lasers.

After an initial grating channeled the particles through small spaces, they moved onward in waves that measured between 10 and 22 quadrillionths of a meter. This brought them into a superposition of possible paths through the device, which researchers could detect with another grating at the end of the line.

This finding suggests the particles' positions are not fixed during the unobserved portion of their journey. The particles exhibited a "delocalization" effect many times larger than the size of any individual particle.

At larger scales, matter generally becomes too complex and entangled with the environment for individual superpositions to be distinguishable. Known as quantum decoherence, this collapse from a superposition to a definable position may explain why we don't observe quantum mechanics in macroscopic systems.

Related: Scientists Just Admitted Nobody Really Gets Quantum Physics

Yet there is no defined size limit on quantum mechanics, and as the new study illustrates, we are not as far removed from it as we might think.

As previous research has suggested, perhaps the different possibilities represented by quantum superposition are all equally valid – and rather than collapsing into a single reality, instead branch out to form a multiverse of possibilities.

The study was published in Nature.