In the beginning, life was simple. Then, about half a billion years ago, biology got complicated. Identical cells shrugged off the shackles of conformity and divided up the chores between them, evolving into the first members of the animal kingdom.

Exactly what this animal prototype looked like has long been the subject of debate. A new study has now revealed the line between ancient microbes and primordial animals might have been crossed by an early form of stem cell.

Today, biologists tend to support one of two contenders for 'Earth's first animal'. In one corner, there's Team Sponge. In the opposing corner, Team Comb Jelly.

Each camp has good reasons to suspect the ancestor of kingdom Animalia resembled their particular phylum more closely than any other.

Sponges have the kind of anatomy we'd imagine of a primitive animal. Comb jellies look far more complex, but have remarkably ancient-looking genomes.

Biologists from the University of Queensland in Australia have now looked beyond the genetic code inside sponge cells by analysing what's known as a transcriptome - a description of genetic activity as cells go about their lives.

Transcriptome analysis is rapidly becoming the tool of choice for researchers who want to know how cells with identical genomes behave in unique ways.

"This technology has been used only for the last few years, but it's helped us finally address an age-old question, discovering something completely contrary to what anyone had ever proposed," says biologist Sandie Degnan.

"Now we have an opportunity to re-imagine the steps that gave rise to the first animals, the underlying rules that turned single cells into multicellular animal life."

As with all animals, the cells making up our own bodies are individually suited to performing specific tasks. This differentiation sets our organisms apart from mere uniform clumps of cells clinging together in the hope that there's safety in numbers.

For more than a century, biologists imagined those first differentiated colonies as a close relative of modern members of the phylum Porifera – the humble sponge.

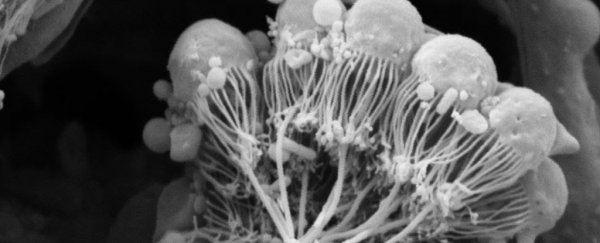

Since the cells called choanocytes lining their guts look suspiciously like free-living, tail-whipping organisms called choanoflagellates, biologists figured the case was closed on 'world's first animal'.

"Biologists for decades believed the existing theory was a no-brainer, as sponge choanocytes look so much like single-celled choanoflagellates – the organism considered to be the closest living relatives of the animals," says Degnan.

But as biologists all know, looks can often be deceiving.

Choanoflagellates might look like they simply teamed up one sunny day 600 million years ago to make a sponge, but research has shown there are significant differences in their respective genomes and biochemistries.

To further test the connection, Degnan and her research team compared the transcriptomes, behaviours, and life cycles of three different types of Amphimedon queenslandica sponge tissue with those of a choanoflagellate and two other similar, single celled organisms.

This was less like comparing the genetic libraries of sponge and pre-animal cells, and more like analysing their library cards to see if they were reading from a shared book list. And it turns sponge gut cells and choanoflagellates aren't in the same book club after all.

Even more surprising was the library card belonging to an undifferentiated type of sponge cell called a pluripotent mesenchymal archaeocyte. The undecided cells of the sponge looked far more like an ancestor of early animals than those that had transformed into gut or skin cells.

"We've found that the first multicellular animals probably weren't like the modern-day sponge cells, but were more like a collection of convertible cells," says Degnan's colleague, marine scientist Bernie Degnan.

"The great-great-great-grandmother of all cells in the animal kingdom, so to speak, was probably quite similar to a stem cell."

In some respects, this makes a lot of sense. Animals are made of a greater variety of cell types, when compared with plants and fungi.

Developing a talent for quickly swapping faces could have given our animal ancestors an edge as they grouped. It's possible the first animals set themselves apart by evolving regulatory systems that permitted multiple forms of differentiated cell to exist at the same time in the same population.

Understanding this has implications beyond our evolution. It could also help us unravel the complexities behind cancer.

It's early days for Team Stem Cell, but already it's clear the debate over the earliest animal is far from settled.

This research was published in Nature.