Researchers have discovered an unknown species of bacteria living in shale oil and gas wells used for fracking, which they've named frackibacter.

The genomes of species living in two separate fracturing wells in Ohio were analysed, and despite the fact that they are hundreds of kilometres apart, the two bacterial communities were surprisingly similar.

A total of 31 different types of bacterial genome were found at the two sites, including Candidatus frackibacter.

"We thought we might get some of the same types of bacteria, but the level of similarity was so high it was striking," said one of the researchers, Kelly Wrighton, from Ohio State University.

"That suggests that whatever's happening in these ecosystems is more influenced by the fracturing than the inherent differences in the shale."

Although almost all of the microbes found in the survey had already been discovered elsewhere, and many likely came from the surface ponds, the researchers suggest that Candidatus frackibacter could be unique to hydraulic fracturing sites.

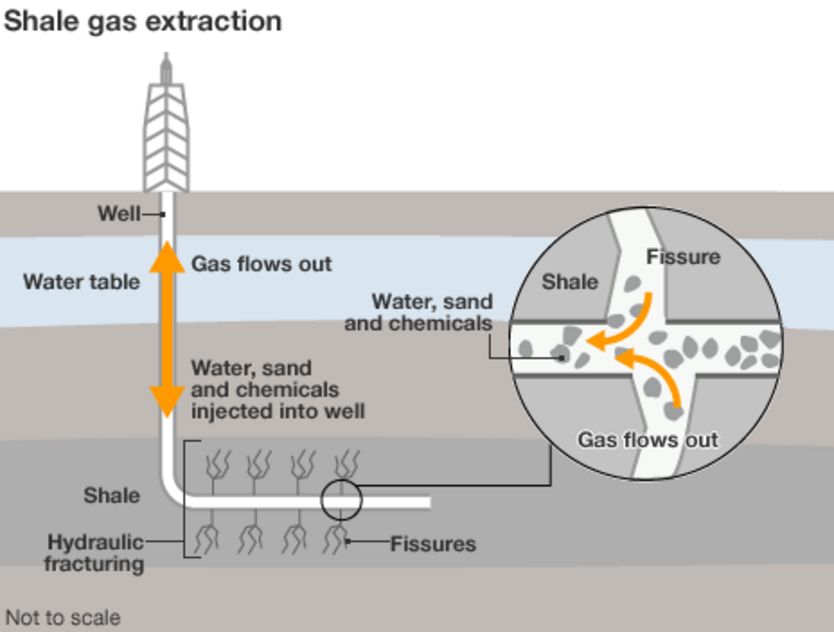

Invented back in 1947, hydraulic fracturing, or 'fracking', has been pretty controversial recently. Fracking involves the fracturing of rock, usually a soft sedimentary rock called shale, by pressurising liquid.

BBC

BBC

The controversy stems from the environmental impacts, health risks from the gas, and possible earthquakes.

No matter which side of the fracking debate you stand on, the implications for this research are pretty exciting when it comes to our understanding of the conditions required for life. The types of environments that these bacterial colonies thrive in are very inhospitable, with high temperatures, pressure and salinity.

"We think that the microbes in each well may form a self-sustaining ecosystem where they provide their own food sources," Wrighton explained.

"Drilling the well and pumping in fracturing fluid creates the ecosystem, but the microbes adapt to their new environment in a way to sustain the system over long periods."

The researchers say that the microbes are protected from the salinity by creating compounds called osmoprotectants to keep them from bursting apart.

The bacterial communities also form a type of symbiotic relationship with each other in these unwelcome conditions. When the cells die, their osmoprotectants are eaten by other microbes, such as frackibacter, which then produce food for the other bacteria called methanogens. This ultimately produces methane, which is a main component of natural gas.

The researchers are looking into how the new-found bacterial colonies could be used to increase the methane output of the fracking sites.

Although the amount of methane produced by the bacteria is only a fraction of the methane produced by the fracking itself, the team points out that the coal mine industry already use microbes to their advantage, and the same could be done for fracking.

"In coal-bed systems, they've shown that they can facilitate microbial life and increase methane yields," Wrighton said.

"As the system shifts over time to being less productive, the contribution of biogenic methane could become significantly higher in shale wells. We haven't gotten to that point yet, but it's a possibility."

The team is now growing the frackibacter and other microbes in the lab under similar high stress conditions to further test their ability to handle pressure and salinity.

The research has been published in Nature Microbiology.