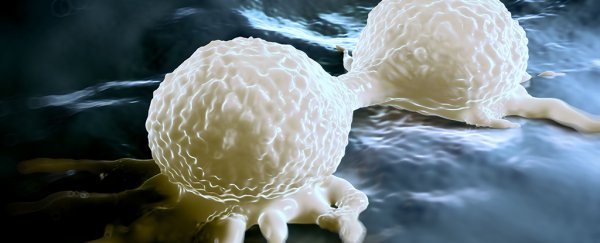

Some types of cancer have a rather cunning way to give themselves a boost by tricking healthy cells inside tumours into popping out particles that look like viruses.

This mimicry has puzzled oncologists for years, but a new study explains exactly what's going on inside these cells, opening the way to new diagnostic tools and possibly novel treatments for some of the most aggressive forms of cancer.

A team led by scientists from the University of Pennsylvania has explored the biochemical mechanisms behind one of cancer's more clever forms of subterfuge, one that uses fake viruses to activate a pathway that helps them grow and resist treatment.

Scientists have known for about a decade that some more aggressive types of cancer express high levels of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs), an action usually triggered by the presence of viruses.

"The conundrum was that in most cases, there was no viral infection in these tumours," says the lead researcher Andy J. Minn from University of Pennsylvania.

"We've been studying this problem for many years, and it's a puzzle we were motivated to solve because cancers with this kind of anti-viral signalling can be particularly aggressive."

Interferons are proteins made by host cells in response to pathogens such as viruses, acting as a signalling system to switch on pathways that can activate an immune response.

Researchers had previously found that they could encourage breast cancer cells to express ISGs by making them come into direct contact with healthy 'builder' cells called fibroblasts.

In this latest research, the team found that the fibroblasts then shed tiny fluid-filled bubbles called exosomes, containing a type of RNA molecule normally shielded inside the cell called RN7SL1.

This particle belongs to a class of molecules that sort and secrete proteins made by the cell, a rather useful tool for viruses that might want to hijack the cellular machinery for its own end.

When a section of RN7SL1 is exposed through the exosome, the cancer cells are alerted into thinking a virus is at work, explaining why they express high levels of ISG.

This false alarm boosts the cancer cell's replication and kicks up their resistance to therapies, making them more aggressive and harder to kill.

The question was, exactly how did these cancer cells force fibroblasts to produce these pseudo-viruses?

In this study, the researchers showed how the cancer cells employed a signalling system to trigger the release of RNA that's normally hidden away.

"The ability of cancer cells to specifically instruct the fibroblasts to expose the viral-like end of RN7SL1 is a key discovery," says Minn.

If that section of the RNA molecule could remain hidden, cancer cells wouldn't treat the fibroblast's exosomes like viruses. That could prove to be a pathway to a treatment that could calm down more aggressive forms of cancer.

Other therapeutic targets could include the mechanism itself – a type of signal exposed on the outside of cancer cells called NOTCH.

Blocking NOTCH might also prevent fibroblasts from releasing virus-like exosomes.

"Since we can test the blood of cancer patients to measure the presence of exposed RN7SL1 in exosomes, we can potentially identify patients whose cancers will be the most aggressive because of this virus mimic," says Minn.

"Now that we understand how the exposed RNA is generated, we can look to potential therapeutic targets."

One particularly nasty type of tumour that has been seen to use this tactic is triple-negative breast cancer, a disease that makes up 15 percent of breast cancers and is distinguished by a lack of receptors for estrogen, progesterone, and HER2/neu.

Without those receptors, breast cancer treatments that involve tamoxifen and trastuzumab don't have anything to attach to. Chemotherapy is fortunately successful in most cases, but anything that can make the tumour less aggressive and more responsive to treatment has to be a bonus.

We'll take any advantage we can get our hands on in an effort to block cancer's insidious tricks.

This research was published in Cell.