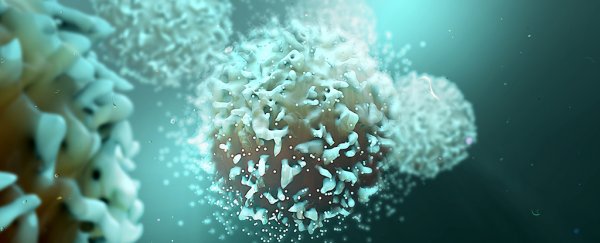

Researchers have invented a new type of cancer immunotherapy by injecting tumours with a series of stimulants. The experimental therapy attracts the body's own immune system's attention, so it can come and destroy the cancerous masses.

The radical new approach has already shown promise in patients with an advanced form of non-Hodgkin's lymphoma that resists conventional treatments, and is currently being tested on a variety of stubborn cancers.

The result can be described as turning the tumours into "cancer vaccine factories", because attracting the body's immune cells to the cancer site is a method known as in situ vaccination.

Researchers at Mount Sinai in New York developed the immunisation technique in their efforts to understand why the promise of recruiting cell-killing T-cells in attacking cancers is such a hit and miss affair.

On paper, employing white blood cells to assassinate rogue tissue such as cancer makes perfect sense. Simply 'prime' them with the chemical equivalent of a mug-shot, and off they go in search of their target.

In practice, getting a T-cell to recognise cancer isn't a simple affair.

For one thing, tumours use a crafty set of disguises called checkpoint blockades. These are signatures on the cell's membrane that tells the immune system it's just a regular old cell just minding its own business so please move on thank you very much.

Checkpoint blockade immunotherapy inhibits these signatures to let the T-cells do their job. But again, not all cancers make this easy. An incurable type of blood cancer called an indolent non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (iNHL) is one example.

By most accounts it should be a great candidate for T-cell therapy. Unfortunately T-cells have a hard time recognising this particular blood cancer.

To get to the bottom of the issue, the Mount Sinai researchers looked at how immune cells can be primed to recognise iNHL easily in the lab, while demanding a more involved process known as cross-presentation inside the body.

The difference suggested T-cells just needed a helping hand. Cross-presentation requires an intermediate primer called a dendritic cell to present specific cell markers to toxic T-cells. Luckily it can be summoned with the right kinds of stimulants.

One stimulant is needed to call the dendritic cells to the tumour. A second stimulant puts the cells into action, encouraging them to present chemical signals called antigens on their surface - like Wanted! posters that tell other parts of the immune system what to look for.

Injected into a tumour with some localised radiotherapy to stir things up, these two stimulants can potentially turn a cancerous growth into a recruiting agency for its own killers.

The therapy was put to the test in a clinical trial made up of 11 patients in advanced stages of iNHL, where it induced both anti-tumour T-cell responses and varying degrees of remission far from the 'vaccination' site.

Not only is this good news for lymphoma patients, the success should in theory be applicable to other cancers.

"The in situ vaccine approach has broad implications for multiple types of cancer," says Joshua Brody, Director of the Lymphoma Immunotherapy Program at Mount Sinai.

"This method could also increase the success of other immunotherapies such as checkpoint blockade."

Additionally, mice became responsive to checkpoint blockade therapy when it was combined with the vaccine, although this part is yet to be tested in humans. In fact, the combination doubled cancer remission in mice from 40 percent to around 80 percent.

This impressive combo potential is currently being clinically evaluated in patients with lymphoma, breast, and head and neck cancer. Meanwhile, tests involving the vaccine on its own are being conducted on individuals with liver and ovarian cancer.

There's a long way to go before we can add this tool to the arsenal of treatments already in place for dealing with cancer.

But with all signs looking good, we can look forward to a new treatment for a slow growing but deadly disease currently considered to be incurable.

Time will tell if it ultimately helps extend lifetimes by a considerable degree. If it's one thing we know about cancer, it rarely makes our job killing it so easy.

This research was published in Nature Medicine.