Centuries of illustrations and photographic images suggest intensive hunting and poaching have altered the appearance of rhinos.

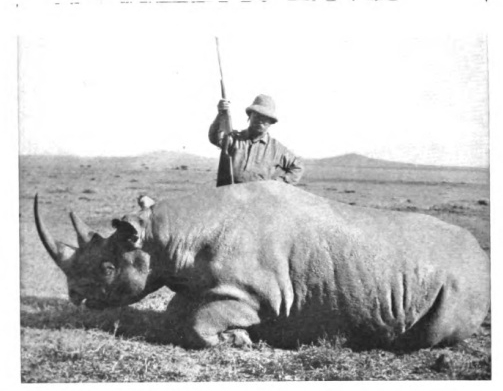

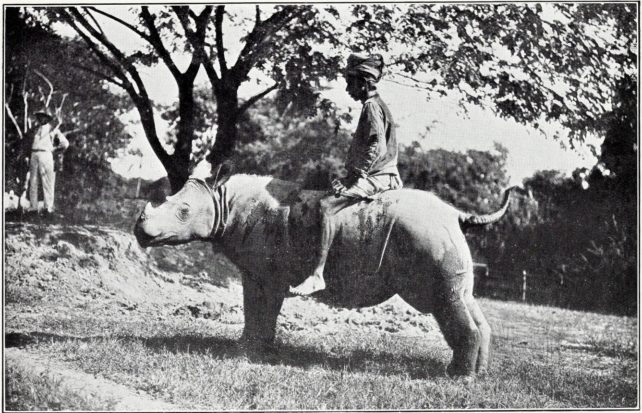

Arranged like a conservation flipbook, the photographs alone reveal a steady decline in the length of rhino horns from 1886 to 2018.

The trend is clear in all five species of rhino, and researchers think the changes are due to intensive hunting and poaching.

"We were really excited that we could find evidence from photographs that rhino horns have become shorter over time," says University of Cambridge zoologist Oscar Wilson, now at the University of Helsinki in Finland.

"They're probably one of the hardest things to work on in natural history because of the security concerns."

Today, every species of rhino bar the white rhino (Ceratotherium simum) is threatened by habitat loss and hunting. Africa's Black rhino (Diceros bicornis), the Javan rhino (Rhinoceros sondaicus), and the Sumatran rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) are particularly endangered.

But even among white rhinos, the northern subspecies now consists of just two female individuals. Preserved sperm and artificial insemination is now the only way to produce further offspring.

Of the 500,000 rhinos that roamed Earth at the start of the 20th century, just over 26,000 are left.

Since 2007, poaching and the illegal trade of rhino horns has increased, probably due to rising demand for horns used in traditional Asian medicine.

When researchers analyzed the relative horn length of rhinos depicted in thousands of images from the sixteenth century onwards, they found the horn-to-body length ratio is decreasing in all five rhino species.

The authors suspect that over time, humans have been killing rhinos with the largest horns, creating a selective pressure against more prominent outgrowths.

In some African elephants, human demand for ivory has created a similar pressure, favoring a tuskless gene at higher frequencies than in the past. In both Africa and Asia, heavy poaching appears to be shrinking elephant tusks.

While a shorter tusk or horn might help protect an elephant or rhino from a poacher, these shrunken appendages are probably not as useful as longer ones.

"Rhinos evolved their horns for a reason – different species use them in different ways such as helping to grasp food or to defend against predators – so we think that having smaller horns will be detrimental to their survival," explains Wilson.

One interesting historical insight from the recent image analysis is that the way humans value rhinos has dramatically shifted over time. Starting in the 1950s, the authors found the rhino went from being commonly portrayed as a fearsome beast worthy of hunting to a symbol of wildlife conservation.

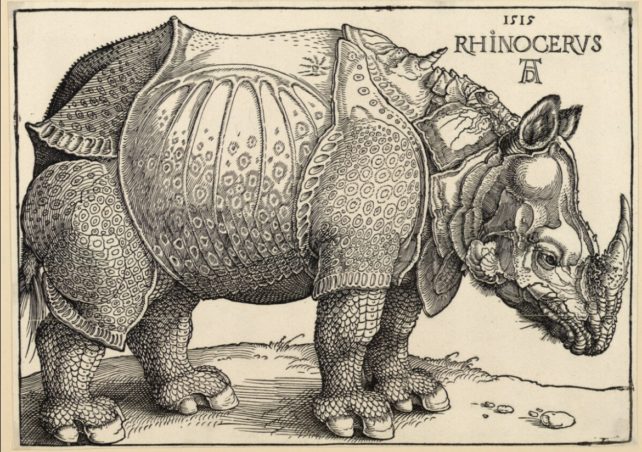

Historic illustrations are not as reliable as photographs for accurate measures of horn size, which is why the authors only considered the latter for their measurements. But even with art, animal representations can reveal something about our changing relationship with nature.

The study's authors suggest using similar image collections to study other large, endangered animals. The analysis might help us learn how a species has evolved through the centuries, and at the same time, how our own attitudes towards wildlife have evolved alongside them.

The study was published in People and Nature.