The concept of a "third eye" is usually associated with perception beyond the physical world, but in a new scientific case, it provides insight into evolutionary development.

Researchers have intentionally genetically modified a common beetle to develop a third functional eye, right in the middle of its forehead.

It builds on previous research in which they caused a beetle to grow a third eye accidentally. Both studies were led by Indiana University postdoctoral researcher Eduardo Zattara.

"Developmental biology is beautifully complex in part because there's no single gene for an eye, a brain, a butterfly's wing or a turtle's shell," explained researcher Armin Moczek of Indiana University.

"Instead, thousands of individual genes and dozens of developmental processes come together to enable the formation of each of these traits. We've also learned that evolving a novel physical trait is much like building a novel structure out of Lego bricks, by re-using and recombining 'old' genes and developmental processes within new contexts."

This means that evolving new features may not be as complicated as scientists previously thought, requiring fewer genetic changes.

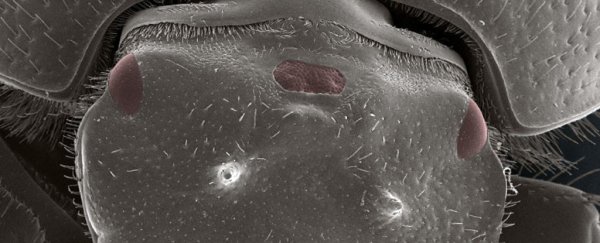

(Eduardo Zattara/Indiana University)

(Eduardo Zattara/Indiana University)

In the original research, the team switched off a gene that is involved in the development of the heads of dung beetles, which caused quite drastic changes to the structure of their heads.

The beetles lost their horns - and developed a compound eye in the middle of their heads. Moreover, it only worked in horned beetles, not other kinds.

"We were amazed that shutting down a gene could not only turn off development of horns and major regions of the head, but also turn on the development of very complex structures such as compound eyes in a new location," Zattara said last year.

"The fact that this doesn't happen in Tribolium is equally significant, as it suggests that orthodenticle genes have acquired a new function: to direct head and horn formation only in the highly modified head of horned beetles."

The development of organs in an abnormal place - called ectopic organs - is a technique scientists use to try and understand how new physical traits evolve.

This has been done in fruit flies - in 1995, a team of scientists published a paper that described how they'd managed to grow ectopic eyes on the wings and legs of fruit flies.

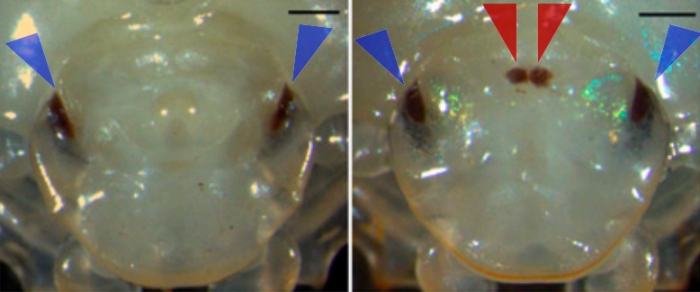

The work of Zattara's team, by comparison, was much simpler. They set out to intentionally grow a third eye in two types of scarab beetle, Onthophagini and Oniticellini, by wiping out just a single gene, the same head development gene from their earlier research.

Control (left) and genetically modified scarab (right). (Zattara et al./PNAS)

Control (left) and genetically modified scarab (right). (Zattara et al./PNAS)

The third eyes the beetles developed actually resulted from fused pairs of eyes. They also lost their horns, or grew much smaller horns, consistent with the earlier research.

The team then conducted multiple tests to confirm that the new eye had the same cell types, genes, nerve connections and behavioural responses as a normal eye.

"This study experimentally disrupts the function of a single, major gene. And, in response to this disruption, the remainder of head development reorganizes itself to produce a highly complex trait in a new place: a compound eye in the middle of the head," Moczek said.

"Moreover, the darn thing actually works!"

The research could help understand how organs develop and become part of a body - which knowledge, in turn, could prove useful in the development of artificial lab-grown organs, for both research and medical purposes.

The team's paper has been published in the journal PNAS.