President Trump may have finally named a science advisor, but that doesn't mean his tweets have become any more scientific.

On Sunday night, Trump decided to give his two cents on the devastating wildfires that are currently burning throughout California.

In the tweet, Trump blamed the exceptional wildfires not on the reality of a rapidly warming planet (as the scientific consensus suggests), but on the "bad environmental laws which aren't allowing massive amounts of readily available water to be properly utilized."

He complained that the water necessary to put out these fires is being "diverted into the Pacific Ocean," and then he suggested that California should clear more trees to stop fires from spreading in the future.

California wildfires are being magnified & made so much worse by the bad environmental laws which aren’t allowing massive amounts of readily available water to be properly utilized. It is being diverted into the Pacific Ocean. Must also tree clear to stop fire from spreading!

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 6, 2018

The next morning, he was back at it, holding California's governor, Jerry Brown, personally responsible for upholding the natural course of the state's waterways.

Governor Jerry Brown must allow the Free Flow of the vast amounts of water coming from the North and foolishly being diverted into the Pacific Ocean. Can be used for fires, farming and everything else. Think of California with plenty of Water - Nice! Fast Federal govt. approvals.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) August 6, 2018

These tweets show a mind-boggling misunderstanding of the entire issue, and they have got to be some of the president's most scientifically inaccurate and ignorant comments on the environment to date.

Because as much as President Trump would like "bad environmental laws" to be the issue here, this is merely his scapegoat for a much larger problem.

"The scientific consensus has predicted worsening fire hazard due to land use change with expanding settlement in the wildland-urban interface, and trends of increasing temperature and drought severity associated with climate change," Maureen Kennedy, an expert in ecology and resource management at the University of Washington-Tacoma, explained to us.

"The tragedy of recent California fires are all consistent with these predictions, and they are sadly not surprising to those who are familiar with the science," she added.

Clearly, President Trump is not one of those people, but exactly how accurate are his tweets? We spoke to Glen MacDonald, a UCLA scientist who studies the causes and impacts of climate change, about whether he thinks water diversion may also be magnifying California's wildfires.

"I wouldn't say that that's true whatsoever," MacDonald told Science AF on the phone.

"What you're seeing is someone thinking about fire in an urban setting, like downtown New York or Queens. That's really different than fighting a wildfire in a place like northern California."

MacDonald says that even if we had more water from the Sacramento or San Joaquin rivers to fight these wildfires, it wouldn't make any difference because a lack of water isn't the problem.

Unlike fires in urban centers, in the areas burning outside city limits, fire hydrants and fire hoses are not fighting the flames. These sorts of fires are tackled using water bombers, which deploy fire retardant over the affected area and not water itself.

Besides, there have been no reports from the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection that there are water shortages. In fact, a spokesperson from the department told the LA Times that there have been zero issues getting water to the fires, as many of them are located near bodies of water.

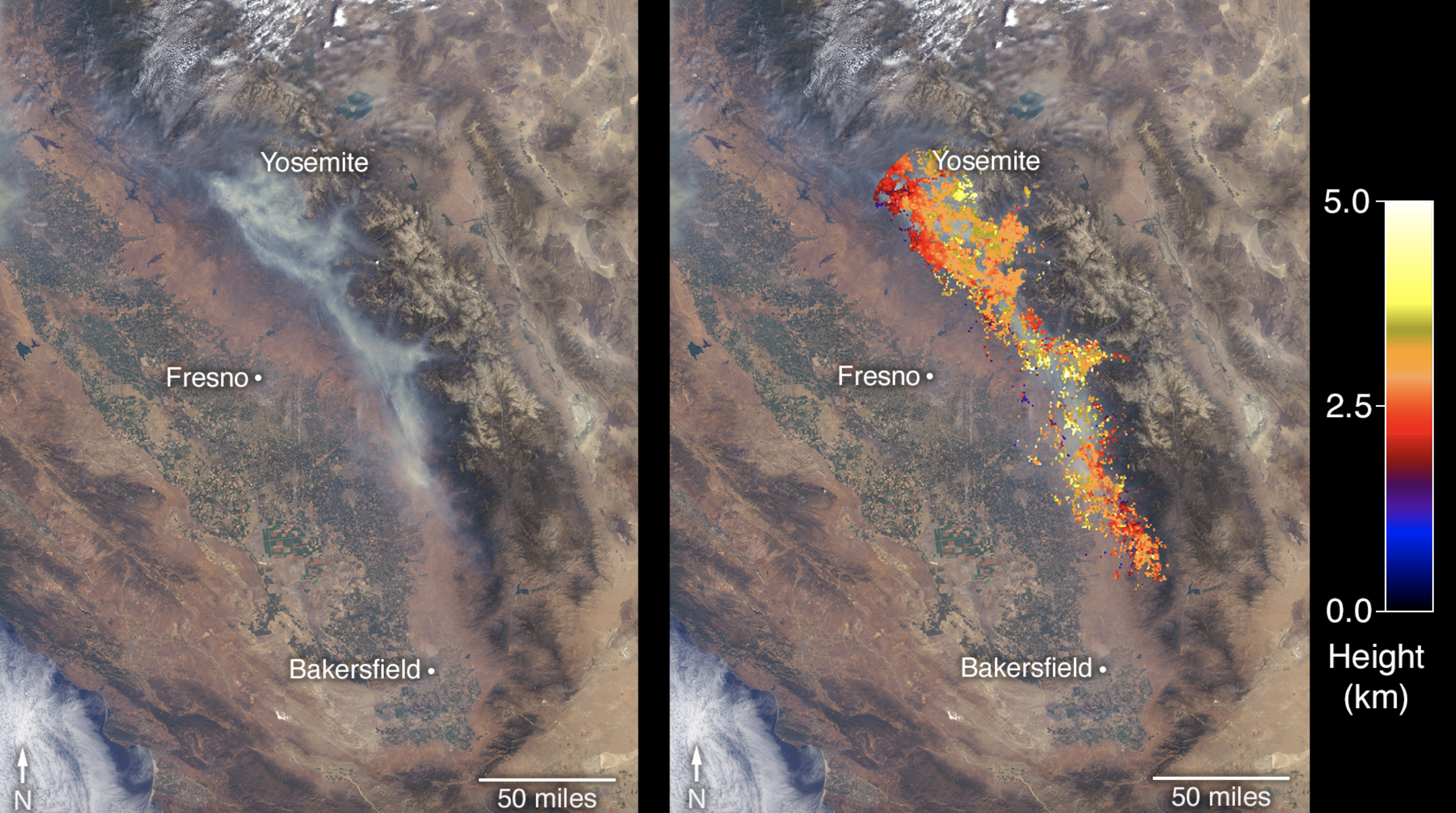

(NASA)

(NASA)

It's unclear exactly what environmental laws Trump thinks are monopolizing California's water supply, but he is most likely referring to federal or state rules that protect river ecosystems, like the Endangered Species Act.

Right now, in northern California, the vast majority of available water is used to grow crops, and the rest of the water is used for ecological function. The water runs down through the river systems and into the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta, which naturally empties into the Pacific.

"It's not diverted there. It's diverted for other uses, which is fair. We need to balance off feeding the nation and supplying our cities, while also having as healthy ecological functioning as possible," explains MacDonald.

"But to say that it's taking water that would be used to fight fires and dumping it into the Pacific Ocean, that's just a complete misconception of the whole situation, both in terms of water and in terms of how fires actually function and burn."

If President Trump got his way, and the river flow to the Sacramento-San Juaquin River Delta was cut off, the water in the delta would become increasingly saline. This would not only impact the ecosystem's precious flora and fauna, it would also hurt local farmers who rely on the delta for crop irrigation.

"If you were to cut the water off entirely from the delta system, you would basically have a dead delta," says MacDonald.

"And you can see what that looks like on the Colorado river, which hardly receives any water at all and is essentially a dead delta."

The President's suggestion to increase tree clearing, however, is a controversial solution not without scientific support. Controlling finer fuels, like shrubs and grasses, is common practice to stop fires from burning with greater intensity and spreading rapidly.

But, as MacDonald explains, you typically aren't trying to burn down the whole forest when you do this.

"You are trying to clear out the lower vegetation," he says.

"So Congress and the President could help by providing more money to the US Forest Service and other entities for fuel management."

The logging of forests to prevent or mitigate wildfires can also be a solution, although there is plenty of scientific debate around this idea. Some scientists argue that clearing untouched forests and already-burned forests is a good idea, while others say the ecological impact is too great a sacrifice to make.

Regardless, President Trump's solutions are not based on the best available science.

In California, wildfires are a natural part of the state's environment, which means that experts have been dealing with this issue for over a hundred years. But despite all the expertise and hundreds of billions of dollars spent, the problem is only getting worse.

Of the 20 biggest fires on record in California, 14 have burned since the year 2000.

Today, there are several more contenders. The Mendocino Complex Fire, which is currently wreaking havoc in northern California, has burned 273,664 acres. It is now the second largest wildfire in the state's history.

The Carr Fire, which is now in its third week of burning, is set to be the sixth most destructive in the state's history, destroying 1,600 structures and killing seven people.

"Given the rate at which the climate is warming and given the fact that this is a fire-prone state, I don't think we can ever have a situation where we don't have wildfires we need to control," says MacDonald.

The tactic now, he says, should be mitigation. We need to figure out how we can protect people's homes, lives and infrastructure. Improved zoning laws, fire management laws and laws that dictate lawful housing materials could all be used to achieve this.

"We are never going to completely eradicate the risk of wildfires here and with the climate changing the way it is, it's really hard to see how we are not going to have more record-breaking fires in years to come," he says.

It's up to humans to figure out how we are going to live with the reality we have created.

If the Trump administration is truly worried by California's wildfires, we would be seeing some sort of evidence-based federal policy. Instead, we just have the President's tweets.