Parasitic gall wasps don't get out much. For the vast majority of their year-long lives, from eggs to larvae, pupae to adults, these tiny insects are entombed in cocoon-like crypts on the leaves, flowers, and stems of oak trees.

When spring rolls around, there's no time to waste, not even for food. The wasps have just days to mate and lay eggs before they die.

For most of the year, the scientists who study these insects must patiently wait. Then, they too must spring into action, magnifying glasses in hand.

So far, there are more than 1,000 identified species of gall wasps around the world, and thanks to the creatures' extreme hermitism and short lifespan, we are still finding more, including the latest addition.

It wasn't an easy journey to describe this newest species. It took researchers at Rice University four years to describe the wasp, even though the insect was found right in their backyard.

The millimeter-long wasp, named Neuroterus valhalla, was first spotted by Pedro Brandão-Dias in 2018 in the oak tree outside the university pub, known as Valhalla.

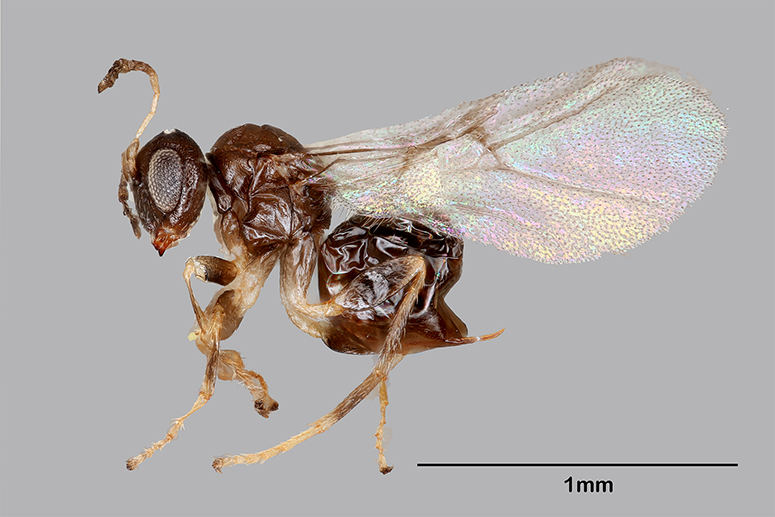

The new species of gall wasp N. valhalla. (Miles Zhang/Smithsonian NMNH)

The new species of gall wasp N. valhalla. (Miles Zhang/Smithsonian NMNH)

Brandão-Dias, the lead author of the paper describing N. valhalla, was actually looking for another gall wasp species known to live in that very tree. But a closer look suggested some of the wasp's legs were a slightly different color than they should be.

There were two possible explanations: Either the wasp was a new species, or it was an alternating generation of an already known one.

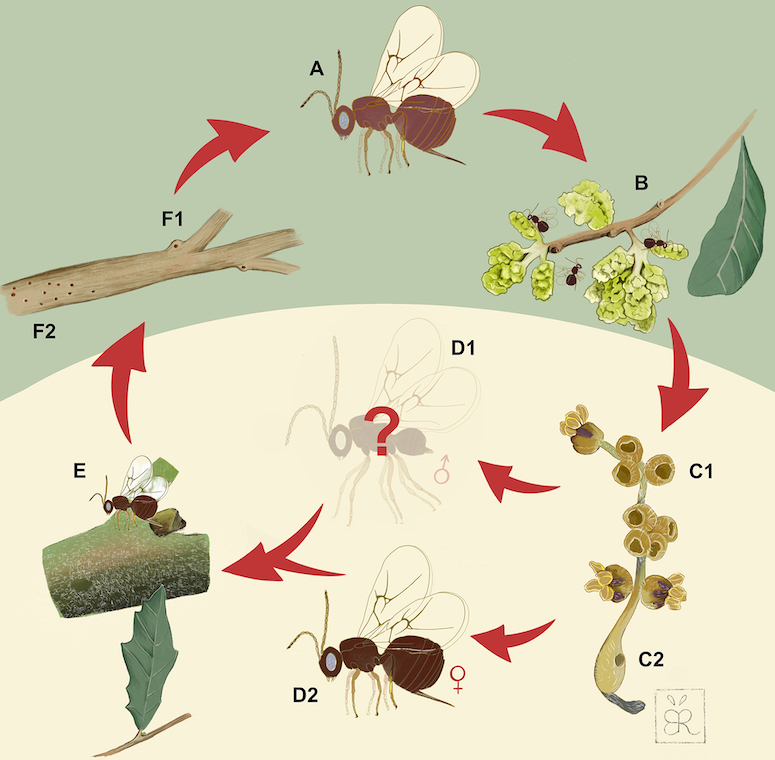

As strange as that might sound, each generation of gall wasp alternates between sexual reproduction and asexual reproduction.

When an asexual female wasp lays its eggs, it produces sexual male and female offspring. However, when those offspring reproduce, they only lay eggs of asexual females.

This reproductive cycle makes the wasps even hard to track over the course of several generations.

To determine if the wasps with lighter colored legs were a new species or an alternating generation of a known species, researchers needed to find both generations.

The first generation of N. valhalla was found in a swelling, or a gall, on the oak tree's catkins. The tree develops these galls when the insects are merely eggs to sequester their hungry appetites.

When the adult wasps emerge in March, however, there are no more flowers for them to lay their eggs on. The adult insects must therefore tuck the next generation into some other structure on the tree. But where?

In 2019, researchers looking for gall wasps in Florida found two different species emerging from crypts near the oak tree's budding stems. DNA analysis confirmed that one of these species was the missing generation of N. valhalla.

Using this knowledge, researchers at Rice collected galls from the catkins on their oak tree and placed them and different tissues from the tree in a petri dish in the lab.

After two or three weeks, the wasps finally emerged from their crypts and began laying their eggs onto nearby stem nodes. That second generation then took 11 months to emerge and lay its eggs on the catkins once again.

Researchers confirmed the life cycle seen in the lab by examining live oak trees in Austin, Texas, where researchers had noticed N. valhalla before, although no males could be found.

The life cycle of N. valhalla. (Illustration courtesy of Barbara Rossi)

The life cycle of N. valhalla. (Illustration courtesy of Barbara Rossi)

Both generations of N. valhalla have just two days to explore the world outside, and given that Texas is now experiencing much colder temperatures than usual in springtime, there's a chance these creatures will struggle to survive in a climate crisis.

"Despite the minute size of its galls, N.valhalla appears to number in the tens of millions every year when it emerges from galls as an adult, making it an example of overlooked and undescribed biological diversity found in the center of a well-known urban center," the authors write.

So what happens if all that diversity one day disappears? No one really knows.

Parasites like the gall wasp form complex interconnected food webs in our ecosystems, impacting not only the oak tree they live in but also other parasites that eat them.

If the gall wasp goes missing, it could set off a domino effect.

A single oak tree, like the one sitting outside Valhalla at Rice University, for instance, could host over 100 species on its own. Yet many gall wasps have only had one generation identified.

That's a whole lot of information we are missing.

The study was published in Systematic Entomology.