For millennia, a towering wonder – the Great Pyramid of Giza – was the tallest human-made structure on Earth, and as the long centuries passed, it forever held onto a hidden secret. Until today.

Scientists have just reported the discovery of a giant void hidden in this largest of Egyptian pyramids, aka Khufu's Pyramid. While we don't yet know what purpose this chamber or hall served, the sheer size of the space suggests it plays an important role in the ancient pharaoh's tomb – maybe even his afterlife too.

An international team of researchers involved with the ScanPyramids project detected the hidden void in investigations that date back to 2015.

The same research team previously uncovered thermal anomalies in the Great Pyramid's structure, and also conducted an analysis of Egypt's Bent Pyramid south of Cairo, which enabled them to map its internal structure.

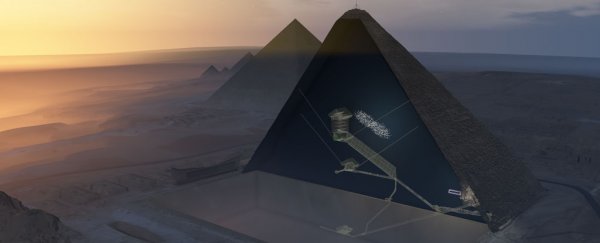

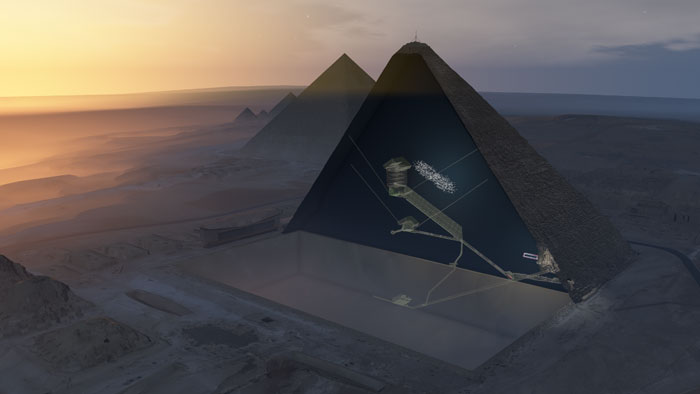

The void, above the inclined Grand Gallery (ScanPyramids)

The void, above the inclined Grand Gallery (ScanPyramids)

Here, the researchers implemented the same kinds of techniques – non-invasively imaging the Great Pyramid's insides by using muons: by-products of cosmic rays that are only partially absorbed by stone.

This method, called muon radiography, works kind-of like an X-ray, as the muons bounce around inside the structure and provide an outline for a 3D reconstruction of the space. This sets it apart from infrared thermography, which detects temperature variations inside a structure.

It might sound like science fiction, but it's actually an imaging method that's been used for decades, only the ScanPyramids team has equipment with much higher sensitivity at their disposal.

Using three different kinds of muon detection techniques – involving both devices installed inside the Great Pyramid (within the Queen's Chamber) and outside it – the researchers identified the large hidden void, which they say is the first major inner structure discovery in the Great Pyramid since the 19th century.

Located above the Grand Gallery – the largest known chamber in the pyramid up until now – the void is estimated to be at least 30 metres (98 feet) long, with a cross-section similar in size to the Grand Gallery underneath it.

The Grand Gallery (ScanPyramids)

The Grand Gallery (ScanPyramids)

"While there is currently no information about the role of this void, these findings show how modern particle physics can shed new light on the world's archaeological heritage," the authors write in their paper.

At present, the ScanPyramids researchers are unwilling to speculate on what the void may represent in terms of its architectural and historical significance, but they're hoping that their discovery will give Egyptologists the raw data to explain what this chamber – or perhaps series of smaller, connected chambers – could represent.

There's still a lot we don't know, the team acknowledges. For starters, it's yet unclear whether the giant void is built level with the ground, or inclined at an angle similar to that of the Grand Gallery below it.

Before more is known, the team hesitates to hypothesise further, not wanting to add to the swirl of unfounded speculation that has always surrounded pyramid research.

"There are so many theories about how the pyramids were built. There are so many theories about potential hidden chambers, but the problem is that those theories are only theories," the team explained at a conference announcing the results.

"That's why when we designed this mission… we wanted to be agnostic in terms of theories. We have new technology… let's use it without any a priori [theory] and see what's inside this pyramid."

The void's location, if not inclined (ScanPyramids)

The void's location, if not inclined (ScanPyramids)

The researchers say more research is being conducted now – and more announcements will be on their way soon – but until those new findings are shared, there's one thing the researchers will admit: this strange void didn't get there by chance.

"When you know the pyramid, and you know the perfection of the pyramid, it's very strange to imagine, that [the void resulted by] accident."

Update (6/11/17): Since the discovery made headlines last week, archaeologist and former Egyptian Antiquities Minister Zahi Hawass has criticised the announcement, telling AFP the ScanPyramids team "showed us their conclusions, and we informed them this is not a discovery."

Hawass, who heads a scientific committee overseeing the project, said "[t]he pyramid is full of voids and that does not mean there is a secret chamber or a new discovery".

In fairness to the ScanPyramids team, the researchers have sought to emphasise that they are not calling what they've found a 'chamber', as they are not making any claims about the architectural or cultural purpose of the space their instruments detected – and they also acknowledge the void observed could be made of connected, smaller spaces.

Nonetheless, the head of the government's antiquities council, Mustafa Waziri, echoed Hawass's criticisms of the announcement.

"The project has to proceed in a scientific way that follows the steps of scientific research and its discussion before publication," he said.

In separate comments made to Ahram Online, Hawass asserted the pyramid's builders could have intentionally left large voids and spaces as deliberate construction gaps for the benefit of the overall structure, meaning the new void located wasn't necessarily any kind of room.

"This project should be scientific and not a search for hidden passages and chambers to attract public attention and those who like to claim that the pyramids were built by aliens," Hawass said.

Hawass says the scientific committee overseeing ScanPyramids' research intends to publish their own paper on the new findings.

With ScanPyramids also expected to be unveiling new announcements in the near future, it seems it won't be long before we have more information about this unseen space in the Great Pyramid – whether it's a kind of a chamber, or something else entirely.

"I think the biggest takeaway is that new technologies will evolve to give us new perspectives on old sites," archaeologist Sarah Parcak from the University of Alabama, who wasn't involved with the research, told Forbes.

"[But] it's going to be very hard to confirm the new finding by any [archaeological] means – which is obviously problematic for the scientific process. It requires archaeological interpretation and confirmation."

The findings are reported in Nature.