From the southeastern shores of Australia, a new fossil has just given us a never-before-seen species of prehistoric baleen whale.

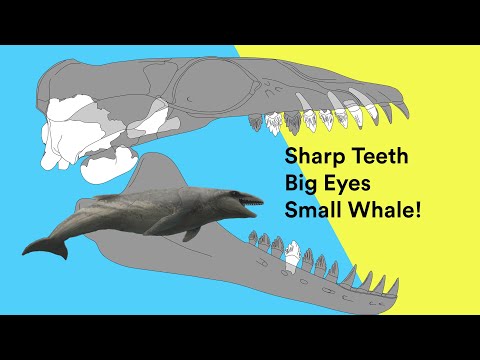

It swam the waters around the southern continent 26 million years ago, using its large eyes and razor-sharp teeth to rule its little corner of the ocean.

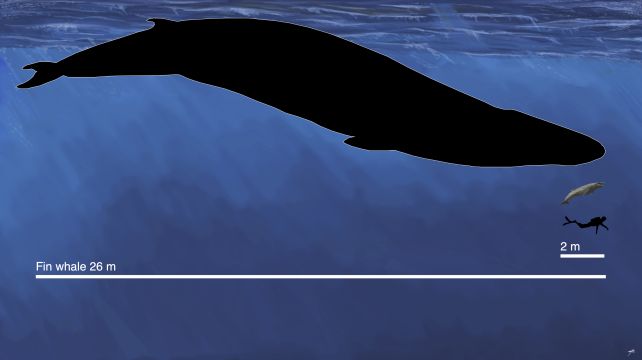

But there's a twist in this tale: unlike the whales that reign today, their numbers including one of the largest animals the world has ever seen, the newly discovered Janjucetus dullardi was tiny – around the size of a human, or a prehistoric penguin.

Actually, it's just one of a whole plethora of tiny whales that swarmed the waters around Australia, before whales started to balloon in size about 5.3 million years ago.

Related: A Human-Sized Penguin Fossil Has Turned Up in New Zealand, Again

"It's essentially a little whale with big eyes and a mouth full of sharp, slicing teeth," says paleontologist Ruairidh Duncan of the Museums Victoria Research Institute and Monash University in Australia. "Imagine the shark-like version of a baleen whale – small and deceptively cute, but definitely not harmless."

The fossil discovered is actually a rare gem, a partial skull, including ear bones and teeth. This allowed Duncan and his colleagues to confidently place the species as a mammalodontid – an extinct genus of ancient baleen whale.

J. dullardi is only the fourth mammalodontid to have been discovered worldwide, and the third discovered in the Jan Juc fossil formation in Victoria, Australia. In addition, its remains are the first to preserve both the teeth and inner ear structure in detail.

The researchers believe that the fossilized remains were from a juvenile, and indicate a whale that would have been around 2 meters (6.5 feet) in length. As a juvenile, it may have grown longer, but not to current whale scales; mammalodontids are thought to have a maximum length of 4 meters.

Those precious ear bones, the researchers say, give crucial insight into how J. dullardi sensed and navigated its environment.

Whales evolved dramatically in the ensuing megayears since J. dullardi was alive. For example, although mammalodontids are technically classified as a baleen whale, they had teeth rather than the baleen structures modern whales used for filter feeding. This indicates that the group is an offshoot of the main lineage that produced today's baleen whales.

Structures such as the inner ear and teeth of J. dullardi can help scientists identify other differences and changes. In turn, that might help reveal why the mammalodontids died out, while other whales went on to thrive.

"This fossil opens a window into how ancient whales grew and changed, and how evolution shaped their bodies as they adapted to life in the sea," says paleontologist Erich Fitzgerald of the Museums Victoria Research Institute and Monash University.

"This region was once a cradle for some of the most unusual whales in history, and we're only just beginning to uncover their stories."

The find has been published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.