Scientists in the US have discovered a new genetic pathway that controls our metabolism configuration, which affects whether excess fat is burned off or stored on the body. This 'master switch' could be used to treat or perhaps one day even prevent obesity, they say, which now affects more than 500 million people worldwide.

"Obesity has traditionally been seen as the result of an imbalance between the amount of food we eat and how much we exercise, but this view ignores the contribution of genetics to each individual's metabolism," one of the researchers, Manolis Kellis from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), says in a press release.

The study focuses on the gene region known as FTO, which was discovered in 2007. Scientists have known that these genes affect obesity, but up until now they haven't been able to figure out why or how.

The researchers studied 100 different tissues and cell types to try and spot signs of genomic control switches, gathering samples from healthy Europeans carrying either the high-risk or non-risk version of the FTO region. In the 'risk' group, the distant genes IRX3 and IRX5 were found to act as control switches, determining whether energy was dissipated as heat - a process known as thermogenesis - or stored as fat. Thermogenesis can also be triggered by exercise, diet, or exposure to cold.

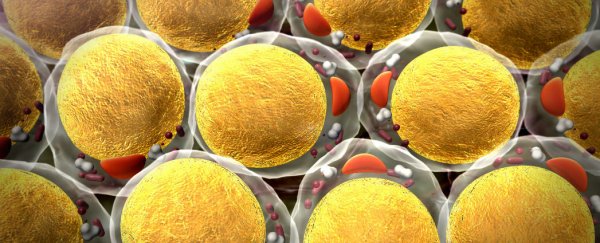

"Many studies attempted to link the FTO region with brain circuits that control appetite or propensity to exercise. Our results indicate that the obesity-associated region acts primarily in adipocyte progenitor cells [fat cells] in a brain-independent way," explains one of the team, Melina Claussnitzer from Harvard Medical School.

"Early studies of thermogenesis focused primarily on brown fat, which plays a major role in mice, but is virtually nonexistent in human adults," she adds. "This new pathway controls thermogenesis in the more abundant white fat stores instead, and its genetic association with obesity indicates it affects global energy balance in humans."

In genetic terms, a difference of just one nucleotide (one of the building blocks of DNA) is enough to change our propensity to become obese. In those who are at risk, a cytosine compound replaces a thymine compound, turning on IRX3 and IRX5. As these genes are turned on, the process of thermogenesis is turned off. The scientists were able to use a genome editing process to flip the thermogenesis switch back on in human cells.

"By manipulating this new pathway, we could switch between energy storage and energy dissipation programs at both the cellular and the organismal level, providing new hope for a cure against obesity," Kellis says.

Of course, a lot more research is required before these findings can be translated into treatments - and a healthy diet and frequent exercise will always be crucial factors in staying trim, no matter how far this genetic research goes.