Generally, it's not considered a very nice thing to make something cry, but new research doing just that could help people who can't.

In a world first, scientists have grown tear glands from human stem cells in a dish, and induced them to produce tears - a significant achievement that could help develop therapies for tear gland disorders, and a step towards regenerative therapies, far into the future.

"We hope that scientists will use our model to identify new treatment options for patients with tear-gland disorders by either testing new drugs on a patient's organoids or expanding healthy cells and, one day, using them for transplantation," said molecular geneticist Hans Clevers of the Hubrecht Institute in the Netherlands.

Tear glands, which sit in the eye socket just above the eyeball, are the organs that are responsible for keeping your eyes lubricated. If anything goes wrong with them, you can end up with eyes that are too moist - or, painfully, too dry.

Current treatments for dry eyes range from eye drops to surgical interventions (or eye drops made out of your own blood, for particularly stubborn cases).

However, treatment options tend to be limited - not least because, according to the researchers, the tear gland, or lacrimal gland, is poorly understood. Using human and mouse lacrimal glands, this is what the researchers sought to redress.

From adult pluripotent stem cells, they first grew lacrimal organoids - tiny, three-dimensional structures that replicate the function of the full organ. Even in a dish, the organoids developed and displayed the structures and functions of the full organ.

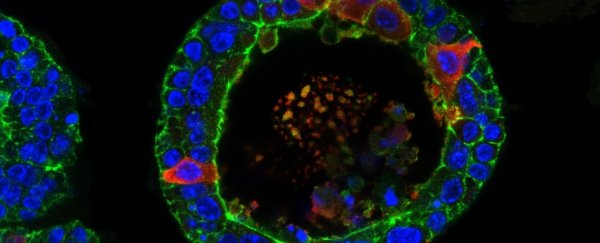

To induce it to produce tears, the researchers exposed the organoid to norepinephrine (also known as noradrenaline), a neurotransmitter that triggers the release of tears. As the researchers recorded, the organoids swelled like a balloon as the cells released the tears on the inside.

Crying organoid. (Marie Bannier-Hélaouët/Hubrecht Institute)

Crying organoid. (Marie Bannier-Hélaouët/Hubrecht Institute)

"The challenge was to get the organoids to cry, as this is a hallmark of the lacrimal gland," said biologist Marie Bannier-Hélaouët of the Hubrecht Institute. "We had to modify the cocktail of factors the organoids are grown in so that they would become the mature cells that we have in our tear glands and that are capable of crying."

On these cells, the researchers conducted single-cell mRNA sequencing to generate an atlas of cells in the tear gland. They were able to determine that the two different types of cells - ductal and acinar - produce different components of the tears produced in the gland.

Next up were the mouse organoids. With these, the team deployed CRISPR-Cas9 to delete a gene called Pax6, which plays a critical role in the embryonic development of organs - including the eyes and lacrimal glands. With Pax6 knocked out, the mouse organoids lost expression for neurotransmitter receptors, and genes involved in secretion, tear production, and retinol metabolism.

Interestingly, all these things can be found in Sjogren's syndrome, a rare autoimmune disease that results in dry eyes and a dry mouth, in extreme cases leading to blindness.

In Sjogren's syndrome patients, loss of Pax6 has also been observed in the conjunctiva, the tissue that lines the eyelids and coats the whites of the eyes. These organoids could therefore help understand and treat this mysterious illness.

Finally, the team wanted to test the possibility of using lacrimal organoids for transplantation. They took some of their human lacrimal cells, and transplanted them in a mouse lacrimal gland. Within a fortnight, the cells had grafted and integrated into the gland, and were forming duct structures.

These remained in the gland for at least two months, and some of the human cells were continuing to grow and divide two months later. They were even producing tear proteins.

Of course, human lacrimal tissue transplantation is a long way off. It will need to be tested and perfected in living animals before we can even think about humans, and that process takes - by necessity - years.

In the meantime, however, the team's research may help us better understand tear gland disorders, and find new ways to treat them.

The research has been published in Cell Stem Cell.