Scientists have repurposed human stomach cells into tissues that release insulin in response to rising blood sugar levels in a breakthrough that promises an effective way to manage conditions such as type 1 diabetes.

The experiment, led by researchers from Weill Cornell Medicine in the US, revealed transplants of gastric insulin-secreting (GINS) cells reversed diabetes in mice.

Pancreatic beta cells normally do the job of releasing the hormone insulin in response to elevated sugar levels in the blood. In people with diabetes, these tissues are damaged or die off, compromising their ability to move glucose into cells for fuel.

While GINS cells aren't beta cells, they can mimic their function. The gut has plenty of stem cells, which can transform into many other cell types, and they proliferate quickly. The hope is that those with diabetes could have their own gut stem cells transformed into GINS cells, limiting the risk of rejection.

"The stomach makes its own hormone-secreting cells, and stomach cells and pancreatic cells are adjacent in the embryonic stage of development, so in that sense it isn't completely surprising that gastric stem cells can be so readily transformed into beta-like insulin-secreting cells," says Joe Zhou, an associate professor of regenerative medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine in New York.

Scientists have been trying to get something like this working for many years, without any real success. In this investigation, the team activated three specific proteins in the cells that control gene expression, in a particular order, to trigger a transformaiton into GINS cells.

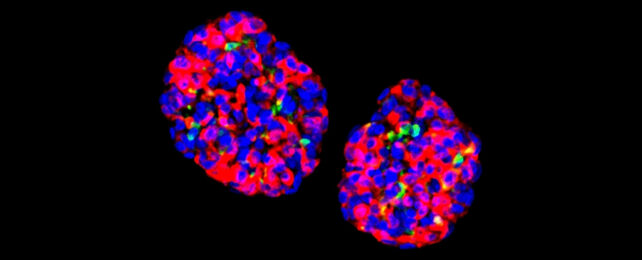

The reprogramming process is highly efficient, and when the cells were grown in small clusters known as organoids they showed sensitivity to glucose. They were then able to show long-lasting effects on diabetes in mice.

Producing GINS cells from stomach cells isn't a particularly complicated process, the researchers say. It only needs a few days to happen, and these new organoids can last for many months after being transplanted, based on their tests.

"Gastric insulin-secreting (GINS) organoids exhibited glucose responsiveness 10 days after induction," the researchers note in their report. "They were stable upon transplantation for as long as we tracked them (6 months), secreted human insulin and reversed diabetes in mice."

The insulin hormone is crucial in regulating blood glucose. Without sufficient levels we run the risk of a variety of health complications. Millions of people worldwide live with diabetes, mostly using insulin injections to help keep glucose levels under control.

It's still very early days for this approach, but it would enable the body to manage insulin levels more naturally again. The researchers note several differences between human and mouse stomach tissue that need to be addressed in future studies, while the GINS cells also need to be made less vulnerable to immune system attack.

Initial signs are promising though. The research adds to a number of ways scientists are looking to tackle diabetes, including diet improvements and tweaking the way that insulin is delivered to the body.

"This is a proof-of-concept study that gives us a solid foundation for developing a treatment, based on patients' own cells, for type 1 diabetes and severe type 2 diabetes," says Zhou.

The research has been published in Nature Cell Biology.