The intense gravitational forces at the heart of supermassive black holes generate intense light shows that are among the brightest things ever seen in the Universe – but that doesn't necessarily mean we can always see them, even when they're close to home.

New research has confirmed the existence of two supermassive black holes in nearby galaxies, previously hidden by clouds of gas and dust that obscured the high-energy fireworks resulting from cosmic matter being drawn into their voids.

"These black holes are relatively close to the Milky Way, but they have remained hidden from us until now," says researcher Ady Annuar from Durham University in the UK, one of a team that investigated a black hole at the centre of a galaxy called NGC 1448.

"They're like monsters hiding under your bed."

Supermassive black holes are actually invisible to us, because they emit no light, but as matter falls over their event horizon boundary, it heats up and produces radiation that can be observed across the electromagnetic spectrum.

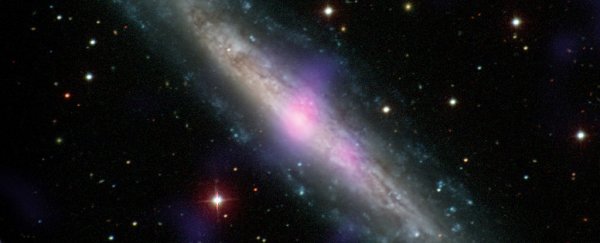

IC 3639. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ESO/STScIThis process, which occurs at what's called the active galactic nucleus – the core of a galaxy containing a supermassive black hole – puts on a brilliant display that can be detected from billions of light-years away, but only if the conditions are favourable.

IC 3639. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ESO/STScIThis process, which occurs at what's called the active galactic nucleus – the core of a galaxy containing a supermassive black hole – puts on a brilliant display that can be detected from billions of light-years away, but only if the conditions are favourable.

The problem is that most active nuclei are thought to be surrounded by a doughnut-shaped cloud of thick gas and dust that blocks much of the light emissions from getting out. If you've got a vantage point to look into the hole of the doughnut, you'll see an incredible light show – but when viewed from the side, you might not catch anything at all.

"Just as we can't see the Sun on a cloudy day, we can't directly see how bright these active galactic nuclei really are because of all of the gas and dust surrounding the central engine," says Peter Boorman from the University of Southampton in the UK, who led a separate study of a black hole in a galaxy called IC 3639.

"As the level of obscuration increases, only the highest energy X-rays can escape to be observed by us," he adds.

The new findings were made possible by NASA's NuSTAR (Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array) – a space-based X-ray telescope.

Using NuSTAR, Boorman's team measured high-energy X-ray emissions coming from IC 3639 – a galaxy some 170 million light-years from Earth, but which is relatively close, considering the Universe is thought to measure approximately 45 billion light-years across.

IC 3639 has previously been observed by NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory and Japan's Suzaku satellite, but the new NuSTAR data are the first to confirm that the galaxy actually contains an active galactic nucleus.

"The black hole [in IC 3639] is so hidden, that it requires highly sensitive observations in the highest energy X-rays to classify it as obscured," says Boorman, whose findings were published in The Astrophysical Journal.

"IC 3639 turns out to be glowing extremely bright due to emission from hot Iron atoms whose origin is not fully understood."

In a separate study, Annuar's team also used NuSTAR to examine a supermassive black hole that's even closer to Earth, at a distance of 38 million light-years away – which is still about 360 trillion kilometres (223 trillion miles) from us, so there's no need to panic.

The study has been published on pre-print website arXiv.org ahead of peer-review, and was presented at the American Astronomical Society meeting in Texas last week.

The discoveries help us to understand more about supermassive black holes and the composition of the matter that surrounds them – which is important to stuff to know, especially since that material can also hide them from our view.

Boorman's team now intends to a begin new NuSTAR survey to help determine the distribution of obscured active galactic nuclei across the Universe – meaning there could be some new surprises in our cosmic backyard before long.

"[These] recent discoveries certainly call out the question of how many other supermassive black holes we are still missing," says Annuar, "even in our nearby Universe."