Antarctica has a new hole. It's more than a kilometre (just under 4,000 feet) deep, barely a hand-span or two in width, and ends in a body of water named Lake Mercer.

Lake Mercer is what's called a 'lost' lake, as it exists deep below the ice, making it inaccessible to usual experiments.

Researchers can now dip into this 'lost' lake and conduct experiments that tell us about the geology and hydrology of a hidden subglacial world, and maybe even find a unique species or two along the way.

It was a celebratory moment for the members of the Subglacial Antarctic Lakes Scientific Access (SALSA) project, who started drilling on the evening of December 23 and reached their goal at a precise depth of 1,084 metres (3,556 feet) on December 26.

(SALSA)

(SALSA)

If this all sounds a little familiar, scientists also boiled through 800 metres (about 2600 feet) of ice in 2013 to reach a blister of water called Lake Whillans.

At around the same time Russian scientists came within a hair's breadth of the 4 kilometre (2.5 mile) deep Lake Vostok, capturing some of its icy surface water before allowing the hole to freeze shut.

The previous year, a failed attempt was made to tap into Lake Ellsworth. It was abandoned after the drill team unsuccessfully tried to link a pair of bore holes that would dig and recirculate water.

Lake Mercer might not be the first hole, but it's still worth our attention. Analysing its contents is vital if we're to understand how Antarctica's water moves beneath such a thick crust of ice, not to mention the flow of organic carbon and other biological processes.

Hundreds of major bodies of water pool deep under the icy crust covering Antarctica, many of which are connected by highways of rivers and streams. Given the role the frozen continent plays in our planet's global climate, and its potential instability, it's scary how little we know about their geology and hydrology.

Busting through such thick ice is no easy task. The 'drill' itself consists of a pencil-sized nozzle that sprays heated water with the force of a locomotive.

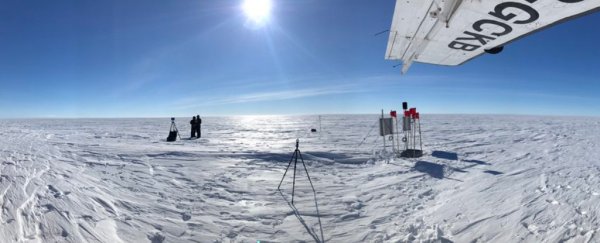

Just to put the nozzle to work, nearly 500 tonnes (about a million pounds) of equipment – including life support for researchers – has been dragged across the flat expanse from McMurdo, a grinding journey that took two months.

A great deal of this equipment has the job of keeping things clean. There's little point in creating a gateway into a relatively pristine environment if you're just going to dust it with contaminants. So all of the equipment was decontaminated with hydrogen peroxide.

Water from local ice was stored in a second nearby hole, and was given extra sterilisation with UV light before being channelled into the pipe. It was also filtered to remove 99.9 percent of particles, and constantly tested.

Still worried? Sitting under so much ice, the lake is under constant pressure. The moment its icy cap was busted, water was forced up into the hole where it quickly froze, meaning hardly any of the heated material from the surface had time to mix with the ecosystem.

As of yet, the only data that has been collected is some footage of the borehole and lake, and a few measurements including depth, conductivity and temperature.

Researchers have been busy testing a piece of equipment called a gravity corer. Dropped down the hole from a great height, it will slam into the sediment at the bottom and drag up a 6 metre (20 foot) cylinder of material for analysis.

What they find will help determine the progress of eroded minerals and decaying matter, which will help inform theories and models on Antarctica's subglacial hydrodynamics and geology.

Of course, there is also the hope of spotting a few undiscovered species along the way.

Lake Mercer isn't exactly sealed off from the outside world, with a turnover of fresh water measured in decades. Its contents dump into the Ross Sea, with most of its water trickling in from the Whillan's Ice Stream to the west.

But given Antarctica has been covered in a thick ice cap for tens of millions of years, there could well be pockets of organisms that have been evolving in the relative isolation of these deep, dark corners.

If nothing else, it's all good practice should we eventually drill into our Solar System's icy moons in search of alien biochemistry.

It's bound to be an exciting 2019 for SALSA's science team. We wish them a world of luck!