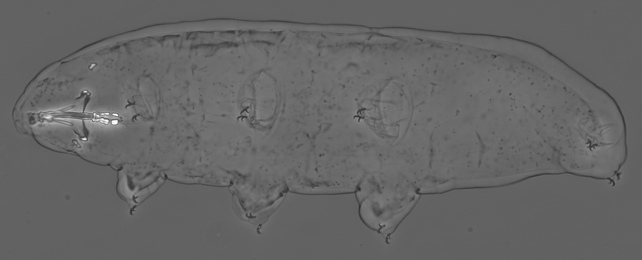

Tardigrades are tiny, incredibly tough animals that can withstand a wide range of dangers, including many that would obliterate most other creatures known to science.

Different tardigrade species have adapted to specific habitats all over the Earth, from mountains to oceans to ice sheets. Their resilience can also help them survive accidental adventures beyond the safety of their native habitats, which can lead to opportunities.

In a pair of studies, researchers reveal a new example of tardigrade biodiversity – a previously unknown species adapted for sand dunes – and offer new evidence suggesting some tardigrades find habitats to colonize by riding inside snails.

The newly discovered tardigrade hails from Rokua National Park in the North Ostrobothnia region of Finland, where researchers found it living on lichen and moss in a dune forest.

The landscape of Rokua has been shaped by glaciers and wind, forming dunes and other features: eskers, kames, and kettle holes. It's also home to a lichen-rich inland dune forest, a habitat threatened by human activity.

Led by Matteo Vecchi, a biologist at the University of Jyvaskyla, a team of scientists visited Rokua to collect moss, lichen, leaf litter, and grass roots from the sand.

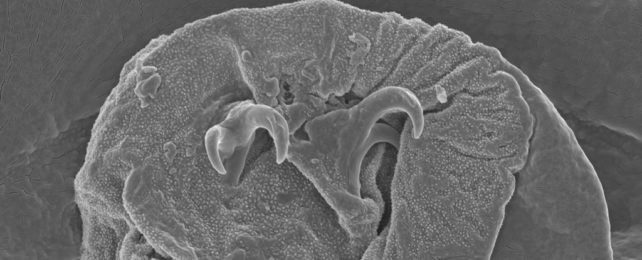

Not only did they find tardigrades, but they found a new species. It becomes just the fifth known member of the Macrobiotus pseudohufelandi complex, a small group of tardigrades with adaptations like reduced legs and claws for living underground.

The researchers named the species Macrobiotus naginae, a reference to Nagini, a snake character from the "Harry Potter" books.

"Formerly a cursed woman who is ultimately and irreversibly transformed into a limbless beast, this fictional character provides a fitting name for the new species in the pseudohufelandi complex, which in turn is characterized by reduced legs and claws," they write.

Like many subterranean animals, these tardigrades may have evolved smaller limbs for a more streamlined shape to crawl through soil or sand, the researchers note.

And while all tardigrades need water, they also have a superpower for surviving long dry spells, which could be helpful in more arid environments.

With anhydrobiosis, tardigrades eject water from their bodies to become a dry, virtually indestructible speck called a tun. In this suspended state, a tardigrade can survive for years or decades, then abruptly reanimate in the presence of water.

The tun state can protect tardigrades from a range of other dangers, too, including extreme temperature, high pressure, oxygen deprivation, X-ray bombardment, being fired from a gun, and exposure to the vacuum of space.

This ability might help tardigrades endure dry spells in their habitats, or it could help them colonize new places by safeguarding them through inhospitable territory if the wind sweeps them away.

Yet in a separate study, Vecchi and his colleagues note the tun state isn't the only way for tardigrades to travel. It's too wet for anhydrobiosis in a snail's gut, for example, but their study suggests ingestion and defecation by snail is nonetheless a viable mode of transportation, though there's no evidence the new species travels this way.

Other tiny creatures like nematodes and oribatid mites can also survive passage through a snail's gut, as can some plant seeds and spores of lichen, moss, and ferns.

This research suggests the same is true for tardigrades, although some other studies have shown that snails don't have a stellar safety record for tardigrade passengers.

The researchers recovered 10 tardigrades from the feces of wild snails (Arianta arbustorum) at a garden in Finland, five of which were alive. They also fed 694 tardigrades to snails in a lab, later retrieving 218 live tardigrades from the snails' feces.

They found 78 dead tardigrades in the feces and reported the other 398 "are supposed to have been digested and destroyed by the snail's digestive system".

Still, 31 percent isn't zero, and the tardigrades who survived also went on to reproduce successfully in the lab.

The snails passed the tardigrades over several days, with the bulk of survivors emerging on day two, the study found. And while snails aren't known for their speed, they can travel faster than tardigrades by virtue of their size.

According to previous studies, on average, these snails move 0.18 to 0.58 meters daily, with a maximum of about 5 meters per day.

The researchers note that a two-day passage through a snail's gut could thus help tardigrades travel up to 10 meters per ride, a considerable distance for animals smaller than 1 millimeter.

The tardigrades don't get to choose where the snails take them and may, in fact, be unwilling passengers. But these snails prefer humid, mossy habitats – just like tardigrades – so any surviving passengers stand a decent chance of ending up somewhere hospitable.

The research was published in Zoological Studies and Ecology.