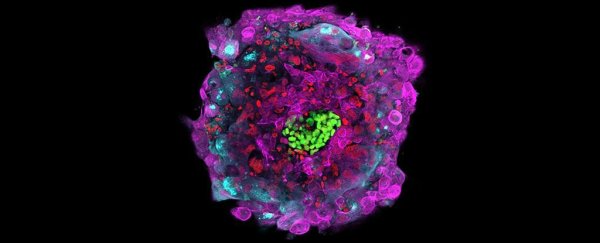

For the first time ever, two groups of researchers have grown human embryos in the lab for 13 days - almost twice as long as previous attempts - giving them unprecedented insight into the crucial time in development. They were even able to see implantation occur, which is something that's never been done before.

The scientists only stopped because they were getting too close to the 14-day legal limit of embryo experimentation, and researchers are already calling for the bioethics guidelines to be rewritten in order to keep this type of research going for any longer.

Until now, researchers have struggled to keep embryos alive in the lab past the first seven days of development - which is when they'd normally be implanted into the uterus.

"This is the period of our lives that some of the most important [biological] decisions are made," lead researcher of one of the teams, Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz from the University of Cambridge in the UK, told the Wall Street Journal. "It was entirely a black box of development that we were not able to access until now."

They were able to keep the blastocysts alive so long this time by placing fertilised embryos (both teams used embryos donated from IVF) in a culture medium of growth factors and hormones designed to mimic the uterus. The petri dish also contained a structure like the wall of the uterus that the embryo could attach to.

Even in this initial study, the teams were able to learn some important lessons. For example, they found that early embryonic development in humans is different from other animals, such as mice.

And, to everyone's surprise, the embryos outside the womb were able to 'self-organise' and form the very early templates of organs without any biological clues from the mother.

"We had seen self-organisation using this system in the mouse embryo, and also in human embryonic stem cells, but we did not anticipate we'd see self-organisation in the context of a whole human embryo," lead researcher of the second team, Ali Brivanlou from Rockefeller University, said in a press release.

"Amazingly, at least up to the first 12 days, development occurred normally in our system in the complete absence of maternal input."

Knowing this could help researchers understand why up to 70 percent of embryos fail to implant during IVF, why birth defects occur, or why so many pregnancies end early. Importantly, it could take them a step closer to being able to improve pregnancy success rates.

But there are big ethical implications. Both teams ended their experiments before day 14, to avoid breaking what's known as the 14-day rule.

Established back in the 1980s by ethicists, the legislation was put in place to stop scientists going so far. They chose that day because it's when the 'primitive streak' - a faint band of cells marking the beginning of the embryo's head-to-tail axis - forms.

After this point, an embryo can no longer split to become twins, or fuse together, so some people consider it the start of 'individuality'. And this is the first time anyone's ever come close to crossing that line.

But in an opinion piece published in Nature alongside the two new papers, researchers are calling for this rule to be updated now that we have the ability to overcome it.

"This was a major scientific milestone," bioethicist Insoo Hyum from Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, and lead author of the accompanying comment, told the Wall Street Journal. "We're now at the stage where the decades-old rule is up for challenge because of the scientific value of what these scientists are trying to do."

His argument is that the 14-day rule has served its purpose as a line in the sand for scientists, but now that we have the technology to pass it, it's time to rethink it.

"The 14-day rule was never intended to be a bright line denoting the onset of moral status in human embryos," Hyum and his co-authors write. "Rather, it is a public-policy tool designed to carve out a space for scientific inquiry and simultaneously show respect for the diverse views on human-embryo research."

Whether or not that will happen remains to be seen, but the fact that we now have the ability to observe the first two weeks of embryonic development outside of the uterus is a huge milestone in its own right, and researchers are definitely going to have their hands full studying this important time.

We look forward to seeing what happens next.

The two papers have been published in Nature and Nature Cell Biology.