A few weeks ago, a huge galaxy orbiting our own appeared seemingly out of nowhere. And now, astronomers have discovered a brand new moon hiding in plain sight at the outskirts of our very own Solar System.

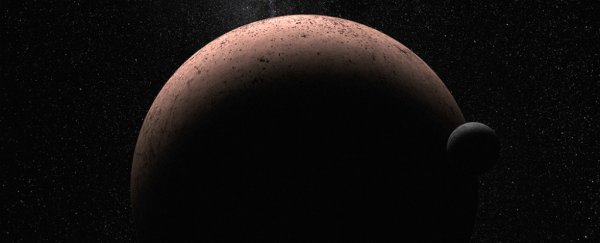

The moon has been spotted orbiting the second brightest icy dwarf planet, Makemake, way out past Pluto in the Kuiper belt, and it's around 161 km (100 miles) in diameter. So what's going on? And why the hell has it taken us so long to spot these not insignificant objects in our own cosmic backyard?

It turns out the newly discovered moon, which has been temporarily named 'S/2015 (136472) 1', or the more friendly 'MK 2' for short, was able to stay hidden for so long because it's incredibly dark.

Just like the newly spotted galaxy earlier this month, the moon reflects such a tiny, tiny amount of light that we've struggled to see it next to the glare of Makemake.

In fact, it's more than 1,300 times fainter than its host planet - so dim that Makemake was previously thought to be the only officially recognised distant dwarf planet without a satellite… a title it's now lost.

It wasn't until astronomers decided to aim the Hubble Space Telescope at Makemake for more than two hours back in April last year that the moon revealed itself. As astronomer Alex Parker, from the Southwest Research Institute in Texas, was going through the data, he spotted a faint point of light moving around Makemake around 20,900 km (13,000 miles) away.

"I was sure someone had seen it already," Parker told National Geographic. He asked fellow researcher Marc Buie about it, who responded with: "There's a moon in the Makemake data?"

"It was at that point that everything got exciting and kicked into high gear," said Parker.

You can see that little point of light in the Hubble images below.

NASA/ESA/Alex Parker

NASA/ESA/Alex Parker

The researchers now want to use Hubble to further study and figure out the orbit of MK2 in the hopes of finding out more about the composition and density of the icy dwarf planet.

"Makemake is in the class of rare Pluto-like objects, so finding a companion is important," said Parker. "The discovery of this moon has given us an opportunity to study Makemake in far greater detail than we ever would have been able to without the companion."

The Kuiper belt is a huge reservoir of frozen material leftover from the formation of our Solar System around 4.5 billion years ago, including several dwarf planets. But scientists still don't understand much about these icy worlds.

One of the ongoing mysteries about Makemake is why it appeared to have different patches of dark material and bright, reflective material across it. But the planet spins every 7.7 hours, so if that was the case, the planet's brightness should change - which it doesn't.

But that could be because the previous infrared data was picking up MK2, not just Makemake, as Parker explained over on Twitter:

The new discovery also increases the similarities between Pluto and Makemake - Pluto's mass also wasn't known until the discovery of its moon Charon in 1978. "That's the kind of transformative measurement that having a satellite can enable," said Parker.

In addition to Hubble observations, he's now hoping that NASA probe New Horizons might be able to swing by Makemake on its way out of the Solar System.

It's pretty exciting to know that there's still a whole lot out there in space we haven't discovered as yet. Who knows, this might also be the year we finally discover Planet Nine. Eyes to the skies, people.

The research has been submitted for peer review, and is published on the pre-print site arXiv.org so others in the industry can add their thoughts.