An antibacterial compound delivered inside microscopic envelopes could soon bring relief to hundreds of millions with the inflammatory skin condition acne vulgaris.

Caused by the overgrowth of a skin bacterium called Cutibacterium acnes, the condition results in uncomfortable eruptions of small pustules.

While there are ways to curtail the bacteria's growth, such as through antibiotics or hormones that reduce the skin oils that feed the microbes, many come with side effects or are becoming ineffective as the bacteria adapts.

The new treatment is based on the antibiotic narasin. Commonly used to prevent infections in livestock and poultry, it could have potential as a treatment C. acnes has yet to develop resistance against.

In this latest study by researchers from the University of South Australia and the University of Adelaide in Australia, and Aix-Marseille Université in France, the antibiotic was shown to be effective against the target pathogen under laboratory conditions.

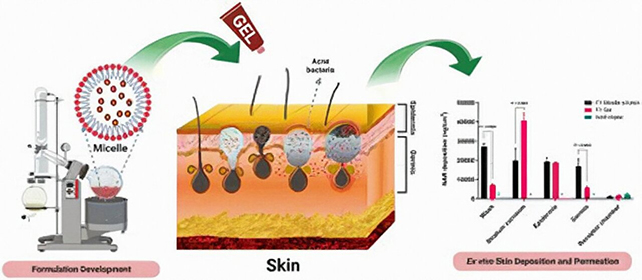

What's more, the team was able to demonstrate nanoparticle delivery could significantly boost the treatment.

When wrapped in tiny capsules a thousand times smaller than a single strand of human hair called nano-micelles, narasin could penetrate much deeper into the skin than it could when it was only mixed with water.

In fact, the team found that their special nanoparticle delivery system improved solubility by more than 100 times, compared to a simple water mix. This was due in part to the use of Soluplus, a compound that improved the solubility of the nano-micelles and the stability of the drug delivery.

"The micelle formulation was effective in delivering narasin to acne targets sites, as opposed to the compound solution which failed to permeate through skin layers," says pharmaceutical scientist Sanjay Garg, from the University of South Australia.

While the researchers used the skin from a pig ear for their experiments here, in the case of actual acne, the drug would need to get into the hair follicles below the skin. These follicles, and the connected sebaceous glands, are where C. acnes thrives.

The next step is to see how this works on actual people of course, but the early signs are promising – based on these results a narasin nanoparticle gel could dive deep to where C. acnes lurks, and do a lot of damage to the bacteria when it gets there.

Another encouraging finding was that the gel produced by the scientists stayed stable at room temperature for a period of four weeks. That's another good sign in terms of being able to get the treatment ready to be used.

Researchers continue to discover more about the causes of acne, and a better understanding of the affliction means a better understanding of what treatments might work best – especially as existing treatments become less effective due to the slow creep of antibiotic resistance.

"Acne severely impacts approximately 9.4 percent of the world's population, mainly adolescents, and causes distress, embarrassment, anxiety, low self-confidence and social isolation among sufferers," says pharmaceutical scientist Fatima Abid, from the University of South Australia.

"Although there are many oral medications prescribed for acne, they have a range of detrimental side effects, and many are poorly water soluble, which is why most patients and clinicians prefer topical treatments."

The research has been published in Nanoscale.