In case you had forgotten just how long-lasting the effects of nuclear fallout are, scientists have reported on radioactivity levels across nuclear sites used from 1946 to 1958. Their results show that the toxic after-effects are still being felt.

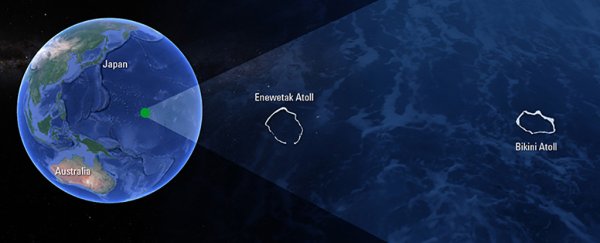

Across the remote Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean, where the US ran a total of 66 nuclear tests across 12 years, levels of radioactivity remain up to 100 times higher than surrounding waters.

The amount of caesium and plutonium in the Marshall Island lagoons has decreased since the 1970s. But regularly taken measurements show that these elements continue to seep out of sediment and groundwater, according to the researchers from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) in Massachusetts.

"The foundations of these island atolls are ancient coral reefs have the porosity of Swiss cheese, so groundwater and any mobilised radioactive elements can percolate through them quite easily," says one of the team, Matt Charette.

That percolation doesn't seem to be happening right now, but the scientists are warning that close monitoring is essential in the future.

Researchers collecting samples near the Runit Dome (Ken Buesseler, WHOI)

Researchers collecting samples near the Runit Dome (Ken Buesseler, WHOI)

Lagoon water samples were collected together with sediment samples packed into containers the size of poster tubes. The team also collected groundwater samples from cisterns, wells, beaches, and other sites.

For the first time on these islands, isotopes of radium were also measured – this radioactive 'tracer' occurs naturally and can point to how groundwater is flowing from the land into the ocean.

The researchers found that the levels of plutonium in the affected lagoons were 100 times higher than the Pacific Ocean as a whole, and the levels of a radioactive form of caesium were about two times higher.

That's actually still within US and international water quality standards designed to protect human health – but it doesn't look like we've got much room for complacency.

In fact many of the people evacuated from the islands while testing took place have never gone back over concerns for their health.

About half of that plutonium appears to be seeping out of the seafloor sediments around Runit Island, reports the team. In comparison, the radioactivity from island groundwater was relatively low.

"Additional studies examining how radioactive plutonium moves through the environment would help elucidate why this small area is such a large source of radioactivity," says one of the researchers, Ken Buesseler.

Part of the study focussed on the Runit Dome on the island of Runit, where weapons testers shovelled around 73,000 cubic metres (95,480 cubic yards) of radioactive soil and debris in the late 1970s as part of a clean up operation.

The concrete cap of the Dome is 46 centimetres (18 inches) thick but the bottom is below the water level and not protected, so experts are worried about possible waste seepage if it gets dislodged by the tidal movements of the ocean.

Thankfully that doesn't appear to be the case for the time being, but the researchers still want to keep close tabs on the site in the future.

"This type of survey will need to be repeated periodically given the large remaining seafloor radionuclide inventories and changing physical and chemical conditions that will accompany sea level rise and deterioration of the Runit Dome," conclude the researchers.

In the meantime, one thing is certain: our planet definitely doesn't need any more nuclear weapons detonating on top of it.

The research has been published in Science of the Total Environment.