Immediately after the Big Bang boomed, the Universe was a trillion-degree 'soup' of unimaginably dense plasma. In a breakthrough experiment, researchers have found the first evidence that this exotic primordial goo did actually slosh and swirl like soup.

In slightly more scientific terms, this gooey soup is called quark-gluon plasma, or QGP. It was the first and hottest liquid ever to exist. Predictions suggest it blazed a billion times hotter than the surface of the Sun for a few millionths of a second before it expanded, cooled, and coalesced into atoms.

As detailed in a recent study, a team of physicists from MIT and CERN recreated heavy-ion collisions like those that created the QGP to explore its properties. For example, when a quark flows through the plasma, does it recoil and splash like a cohesive liquid, or does it scatter randomly like a collection of particles?

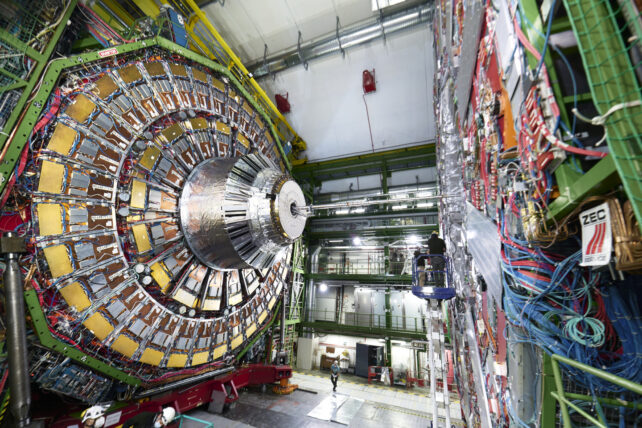

To find out, the researchers analyzed data on collisions between lead particles smashed together at nearly the speed of light inside CERN's Large Hadron Collider (LHC). Such collisions produce sprays of energetic particles, such as quarks, as well as a droplet of the QGP that permeated the infant Universe.

Using a unique strategy that provided a clearer view of the heavy-ion collisions than previous experiments, the physicists traced the motions of quarks through the QGP and mapped the energy of the QGP in the aftermath of those collisions.

"Now we see the plasma is incredibly dense, such that it is able to slow down a quark, and produces splashes and swirls like a liquid. So quark-gluon plasma really is a primordial soup," says physicist Yen-Jie Lee of MIT.

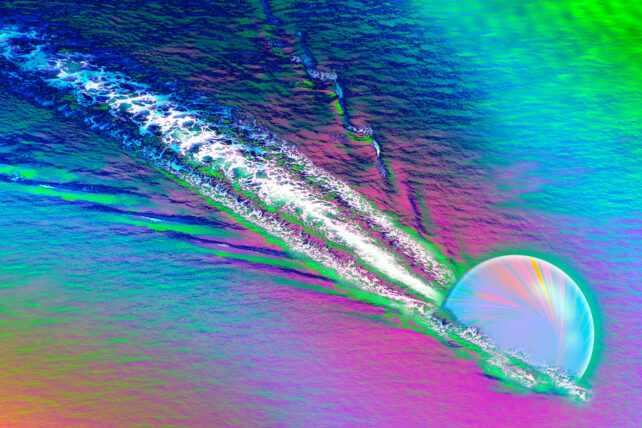

The quarks zipping through the QGP transfer some of their energy to the plasma, losing speed and creating a wake like a speeding boat.

"By analogy, when you have a boat moving through a lake, the wake is water behind the boat that is moving in the direction of the boat. The boat has transferred momentum to some region of water, which is 'following' it," MIT physicist Krishna Rajagopal, who developed a model that predicted the fluid properties of QGP, told ScienceAlert via email.

But rather than seeing a clean wake as you do in water, the researchers had to infer its messy existence in their droplets of QGP.

This requires sorting through tens of thousands of wildly interacting particles, in a trillion-degree plasma that typically exists within the LHC for a quadrillionth of a second, to detect the relatively few particles displaced by the wake.

This is not easy. When quarks are produced in LHC collisions, they never exist alone, Rajagopal explained to ScienceAlert. They usually form alongside antiquarks, their counterpart particles that are identical but oppositely charged. The quark and its antiquark fly off in opposite directions at the same speed, each creating a wake and complicating detection.

So instead of searching for quark-antiquark pairs, as per previous experiments, the physicists searched for a different pair of particles. Sometimes, LHC collisions lead to the creation of a quark and a Z boson, a neutral elementary particle that does not produce a wake because it doesn't interact with the QGP.

However, these events are rare. Out of 13 billion LHC collisions analyzed in the study, only about 2,000 produced a Z boson. But due to the Z boson's lack of interaction with the QGP, the researchers were finally able to analyze the wake caused by a single speeding quark. As Rajagopal's model predicted, the QGP reacted as a liquid, sloshing and swirling in the wake of the quark.

Rajagopal told ScienceAlert that this is "definitive, unmistakable evidence" of the QCP's liquid-like behavior, but the long-standing argument about whether QGP flows and ripples like a fluid may not be settled just yet. Other researchers will surely scrutinize the results.

Related: Quantum Entanglement Found in Top Quarks – The Heaviest Particles Known

Nevertheless, this new technique offers a framework to explore similar processes in other types of high-energy collisions, possibly illuminating one of the most mysterious substances in the history of the Universe.

"In many other areas of science, the way you learn about the properties of a material is to disturb it in some way, and measure how the disturbance spreads and dissipates," Rajagopal said.

And that's part of what makes physics fun – if you aren't sure how something works, just smash it at nearly the speed of light.

This research is published in the journal Physics Letters B.