For the first time, scientists have figured out how to accelerate electrons using protons passing through plasma.

That's a big deal, because it could lead to much smaller and cheaper particle accelerators than the ones we currently rely on.

Right now, if you want to install a Large Hadron Collider (LHC) particle accelerator in your back garden, you need a concrete tunnel about 27 kilometres (nearly 17 miles) long and US$5 billion in spare change.

But this new experiment uses something known as plasma wakefield acceleration – and it takes up just 10 metres or 33 feet of space.

The team behind the Advanced Proton Driven Plasma Wakefield Acceleration Experiment (AWAKE) at CERN in Geneva has been working for five years to get a result like this, and while it's still early stages, this could end up driving a huge improvement in the way we examine the fundamental physics of the world.

"The results shown here are a significant step towards the development of future high-energy particle accelerators," say the researchers.

What happens in existing particle accelerators, like the LHC, is that oscillating electric fields work inside contained vacuums called cavities, creating two opposing charged zones that excite particle beams up to high-energy levels.

These particles can then be smashed together and studied in detail to examine particles at the subatomic level. A long series of cavities are required though, hence the 27-kilometre (17-mile) stretch that makes up the Large Hadron Collider.

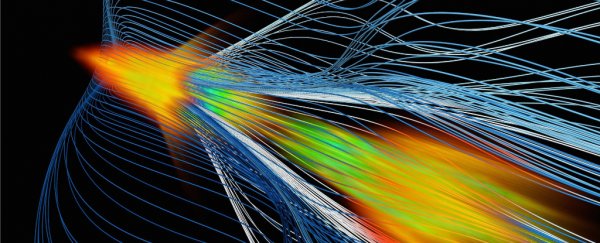

In the new technique, a beam of protons fired through super-hot plasma acts a bit like a boat kicking up waves – these bubbles of intense electrical fields that get created are what's called the wakefield.

If a beam of electrons is then sent through the same container, and timed to synchronise with the electrical fields perfectly, the electrons can ride these waves like surfers, achieving high speeds in a short distance.

You can see AWAKE project leader Edda Gschwendtner explain the process in the video below:

"I think we can soon achieve the highest-energy electron beam around," one of the team, physicist Matthew Wing from University College London in the UK and spokesperson for AWAKE, told Gizmodo.

Wakefields are not a new idea and have been the subject of research since the 1970s, but this is the first experiment to successfully use protons for the initial "drive beam", rather than the lasers or electrons that are usually used.

For all this to work, drive protons need to be obtained from the Super Proton Synchrotron (SPS) at CERN – a 7-kilometre (4.3-mile) tube which also supplies the LHC with protons. With that in mind, we're not quite at the stage where we can fit a particle accelerator into a cupboard – but the signs are good.

In this case, over the space of 10 metres (33 feet), electrons were accelerated to 2 GeV (giga-electron volts). That's much less than existing electron accelerators, which can produce 6 GeV and way beyond that – the current record is 13 TeV, or 13,000 GeV, which is held by the Large Hadron Collider.

However, these other facilities are at least several kilometres or miles long (and much longer in the LHC's case). The researchers think their prototype will scale up well.

Now that plasma wakefield acceleration has been shown to work, the next steps are to refine the processes involved to make them more efficient and capable of operating at higher energy levels. That could take 5-10 years, but we're on the way.

"We are looking forward to obtaining more results from our experiment to demonstrate the scope of plasma wakefields as the basis for future particle accelerators," says Gschwendtner.

The research has been published in Nature.