Researchers recently discovered that eight different psychiatric conditions share a common genetic basis.

A study published this year pinpointed specific variants among those shared genes and shows how they behave during brain development.

The US team found many of these variants remain active for extended periods, potentially influencing multiple developmental stages – and offering new targets for treatments that could address several disorders at once.

Related: Study Traces Autism's Origin to The Rise of Human Intelligence

"The proteins produced by these genes are also highly connected to other proteins," explained University of North Carolina geneticist Hyejung Won in January.

"Changes to these proteins in particular could ripple through the network, potentially causing widespread effects on the brain."

Back in 2019, an international team first identified 109 genes linked in different combinations with eight psychiatric disorders: autism, ADHD, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, major depressive disorder, Tourette syndrome, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and anorexia.

This may explain why these conditions often co-occur – for example up to 70 percent of individuals diagnosed with autism or ADHD have the other too – and why they frequently cluster in families.

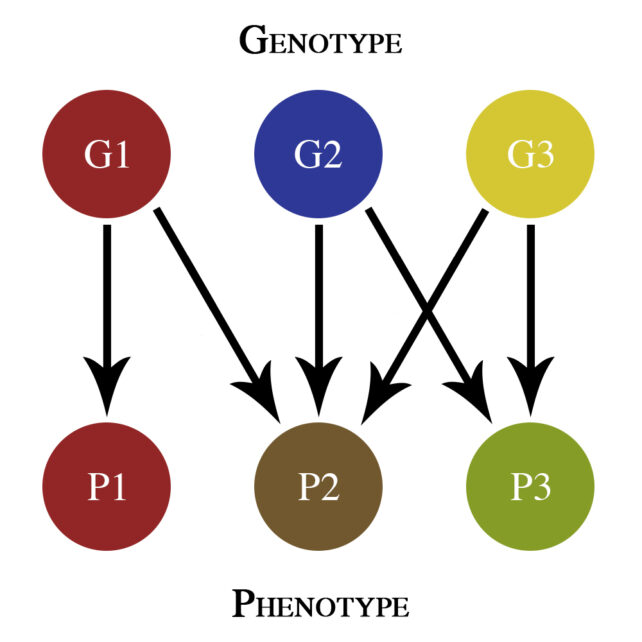

Each of these eight conditions also has gene differences that are unique to them individually, so Won and team compared the unique genes with those shared between the disorders.

They took almost 18,000 variations of the shared and unique genes involved and put them into the precursor cells that become our neurons to see how they could impact gene expression in these cells during human development.

This allowed the researchers to identify 683 genetic variants that impacted gene regulation and to further explore them in neurons from developing mice.

Genetic variants behind multiple seemingly unrelated traits, or in this case conditions, are called pleiotropic. The pleiotropic variants were involved in many more protein-to-protein interactions than the gene variants unique to specific psychological conditions, and they were active across more types of brain cells.

Pleiotropic variants were also involved in regulatory mechanisms that impact multiple stages of brain development. The ability of these genes to impact cascades and networks of processes, such as gene regulation, could explain why the same variants can contribute to different conditions.

"Pleiotropy was traditionally viewed as a challenge because it complicates the classification of psychiatric disorders," said Won.

"However, if we can understand the genetic basis of pleiotropy, it might allow us to develop treatments targeting these shared genetic factors, which could then help treat multiple psychiatric disorders with a common therapy."

This would be a very useful strategy given the World Health Organization estimates 1 in 8 people (almost 1 billion in total) live with some form of psychiatric condition.

This research was published in Cell.

An earlier version of this article was first published in February 2025.