Tiny carbon particles dumped into the atmosphere by industry and transport have been found on the wrong side of the placenta - a critical barrier meant to protect unborn babies from harm.

Only last year researchers spotted ominous flecks of soot in placental white blood cells, the first solid indication that the pollutants could migrate so close to a foetus. Now there's evidence that these potential toxins can creep even closer still.

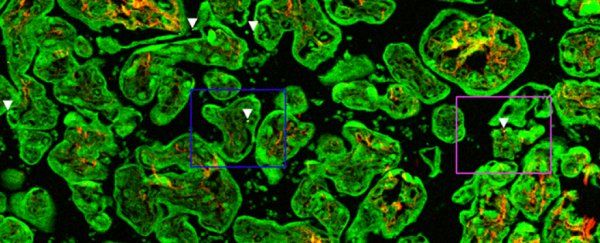

Researchers from Belgium's Hasselt University and East-Limburg Hospital used high resolution imagery to highlight tiny accumulations of black particles on both the mother's and foetus's side of every placenta taken from 28 births.

Further testing on the tiny clumps confirmed they were firmly embedded in the tissue, and were made up of the kind of potentially hazardous 'black carbon' particles emitted by combustion engines and fossil fuel power plants.

While the study stops short of linking carbon particles with birth complications, it does show the barrier at the core of the placenta isn't filtering out enough of the material already associated with a variety of serious health concerns for developing bodies.

Christine Jasoni is the Director of the Brain Health Research Centre at the University of Otago in New Zealand. While she wasn't involved in the study, she finds the prospect of a new disease route alarming.

"There is considerable epidemiological evidence that when a pregnant mother is exposed to air pollution there are long-term consequences for the health of her offspring," says Jasoni.

"The biggest risk is for low birth weight, which significantly increases life-long risk for a collection of diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular disease, asthma and stroke."

The placenta can be pictured as two hands with their fingers interlaced. One hand belongs to the mother and is anchored firmly to the wall of the uterus. The other is technically part of the foetus, consisting of a network of blood vessels that extend down the umbilical cord and into the growing body.

Where those two sets of 'fingers' meet there are structures that keep the mother's and foetus's blood from mixing while still permitting an exchange of gases, wastes, hormones, and nutrients.

As efficient as this barrier between mother and child is, it isn't great at keeping out nasty materials such as alcohol, various pathogens, and even some nanosized particles.

This latest study strongly indicates that bits of black carbon that enter the lungs of a mother can not only worm their way through her own vascular system into her placenta, but are capable of slipping past vital structures into foetal tissue.

The researchers also showed the concentrations of these deposits increase with the level of air pollution in the external environment by comparing the placentas of 10 mothers living near busy roads with another 10 living in quieter zones.

An additional five placentas from spontaneous preterm births were also studied, revealing particles could be detected from as early as just 12 weeks into gestation.

Given the known links between air quality and foetal development, knowing this wall between mother and child is permeable to nanoscale soot particles is worth investigating.

But it's also worth keeping in mind that this could also be a sign of nature living up to expectation.

"Since one of the functions of the placenta is to act as a barrier preventing toxins passing from the mother into the foetus, the placenta could be seen here as performing its normal job – accumulating the black carbon particles so they don't get into and damage the foetus," says Jasoni.

Still, knowing the difference between a healthy-looking placenta and one that's overloaded, could help researchers pinpoint the mechanisms behind the hazardous effects of black carbon.

From birth through early development and well into our twilight years, the fine particles of carbon hanging about in the atmosphere jeopardise our health on a range of levels.

While nations such as the US have worked hard over the years to improve air quality, there's still a long way to go. Especially when children who aren't even born yet are among those at risk.

This research was published in Nature Communications.