One of the largest COVID-19 brain imaging studies to date has shed some unsettling light on the disease's impact on our brains.

Even in those with a mild or moderate case, a SARS-CoV-2 infection was associated with "significant" neurological changes and loss of gray matter.

The study looked at the brain scans of 785 people from the UK aged between 51 and 81. The scans were conducted on average 38 months apart, and were done alongside cognitive tests.

"To our knowledge, this is the first longitudinal imaging study of SARS-CoV-2 where participants were initially scanned before any had been infected," write the researchers, led by Gwenaëlle Douaud from the University of Oxford in the UK.

"Our longitudinal analyses revealed a significant, deleterious impact associated with SARS-CoV-2."

Early results of this research were previously released in preprint, and have now been peer reviewed and published in Nature.

The structural changes appeared to be persistent – on average, the scans were conducted 5 months (141 days) after the person was ill with COVID-19 – although how long they last and whether or not they're reversible will need to be the subject of future research.

It's not news that SARS-CoV-2 has an impact on our brains: We already had evidence that infection with the virus could lead to structural changes and inflammation in the brain.

But what's unique about this study is that it's the first to compare people's own brain scans, both before and after COVID-19, which minimizes the possibility that any damage could have been done prior to infection.

The researchers also compared the brain scans to those of people who hadn't been infected with SARS-CoV-2 at all during the study period, thus providing a control group. The researchers were able to do this through access to data from the UK Biobank, which holds health data and imaging taken from volunteers over the years.

Out of the 785 total subjects who were initially scanned, 401 tested positive for COVID-19 before coming back for their next tests. The other 384 had not tested positive for COVID-19 during the study and acted as the control group.

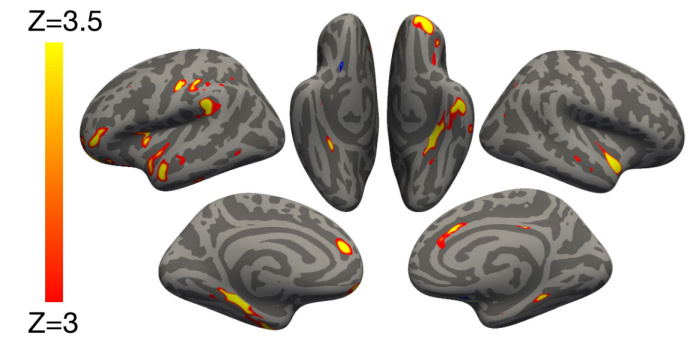

Compared to their first brain scans, those who had been infected had noticeable tissue damage in the piriform cortex, olfactory tubercle, and anterior olfactory nucleus – regions of the brain associated with smell and taste, as well as memory.

These people also had subtly lower scores in cognitive tests than they had before, and had atrophy in the cerebellum – an area of the brain associated with cognition.

Specifically, SARS-CoV-2 infection was associated with a 0.7 percent loss of gray matter in affected brain regions. For context, the authors compare that to the roughly 0.2 percent of gray matter normally lost in adults each year in middle age.

(Douaud et al., Nature, 2022)

(Douaud et al., Nature, 2022)

Above: Image showing the greatest areas of reduced gray matter thickness between participants who'd had COVID-19 and those who hadn't.

To make sure their results were specific to COVID-19, the researchers also performed a control analysis on another, smaller group of 11 people who'd had pneumonia not associated with COVID-19, and found that these brain impacts weren't seen in patients who'd had a regular respiratory illness.

Importantly, many of those who had COVID-19 in the study didn't have a severe case. Even when the 15 people who had been hospitalized with COVID-19 were excluded from the results, the effects of the virus were still visible in the brain.

"The findings of the study are remarkable," said neuroscientist Sarah Hellewell, from Curtin University in Australia, who wasn't associated with the research.

"The authors show that people who had mild COVID-19 infection an average of five months prior had thinning of brain tissue in several key brain regions."

Of course, despite the strengths of this study, there are still big questions left unanswered.

For one, the study didn't have access to data on how severe each individual's COVID-19 case was, outside of whether they were hospitalized. For example, it's not clear what their oxygen levels were throughout their infection.

It's also important to note that the scans were conducted between March 2020 and April 2021, so it's unlikely any of the participants had the Delta or Omicron variants that are now in circulation – so we need to keep that in mind when considering how these results may be related to more recent infections.

Also, these results were analyzed as a group sample and so the results aren't directly applicable to individuals.

"People need not panic if they have had COVID-19. The brain changes observed were relatively small and on a group level, so not everyone had the same effects," adds Hellewell.

"More research is needed to know whether these changes remain, reverse or get worse over time, and whether there are treatments which could help."

Importantly, the study can provide us more insight into how a SARS-CoV-2 infection damages the brain in the first place, something scientists still don't understand.

Douaud and her team suggest three possible mechanisms for the damage in their study.

One is the degenerative spread of COVID-19 via smelling pathways in the brain. Alternatively, the virus itself may not be entering the brain but impacting it in other ways: either through general nervous system inflammation; or by causing the loss of sensory input due to loss of smell.

This is something that further research will need to tease out.

The research has been published in Nature.