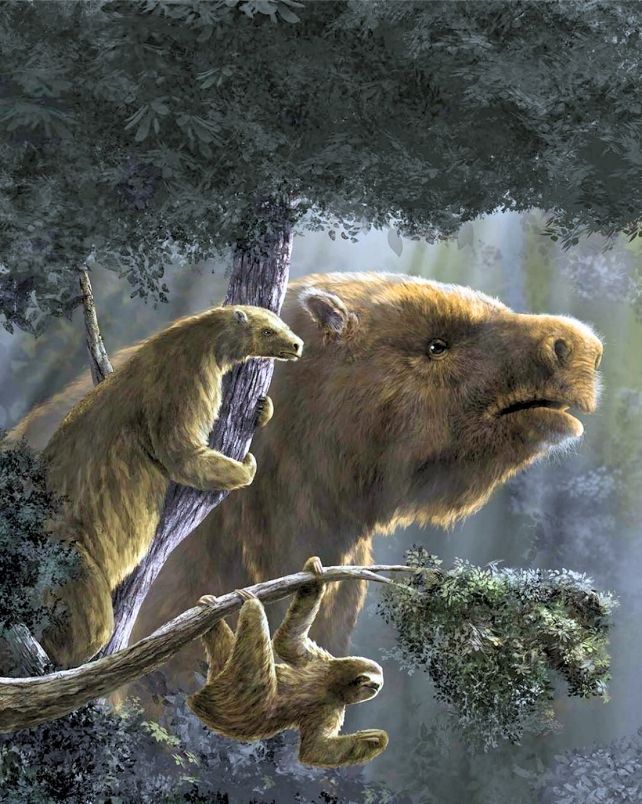

Massive Megatherium sloths once stood as large as Asian elephants, ripping foliage off treetops with prehensile tongues like today's giraffes.

"They looked like grizzly bears but five times larger," says paleontologist Rachel Narducci from the Florida Museum of Natural History.

Megatherium were among a dazzling assortment of more than a hundred different sloth species that once roamed the Americas. Their ancient DNA now tells the likely story of why only six sloth species remain.

Analyzing the DNA of 403 sloth fossils from museum collections, alongside weight estimates and environmental information, a new study has created a detailed sloth family tree. This 35 million years of evolutionary history revealed these once-diverse animals' sizes matched up neatly with the environmental conditions they experienced.

The endearingly dopey mammals we know and love today are so suited to their arboreal environment that they've developed an incredibly strong upper body, have guts designed to hang upside-down, and risk their lives when they descend to poop.

"Living sloths are extremely slow and that's because they have a very low metabolic rate," University of Buenos Aires paleontologist Alberto Boscaini told Helen Briggs from the BBC. "This is their strategy to survive."

But many ancient species were too heavy for tree branches to bear, and stuck to the ground, like Megatherium and Lestodon. Unlike today's sloths, these species were well suited to moving with agility over the earth and had much faster metabolisms.

"Some ground sloths also had little pebble-like osteoderms embedded in their skin," notes Narducci, explaining these rocky bumps were a ground-defense trait they shared with one of their closest relatives, armadillos.

There was even an aquatic sloth, Thalassocnus, that survived life on the arid strip between the Andes and Pacific by foraging in the ocean.

"They developed adaptations similar to those of manatees," says Narducci. "They had dense ribs to help with buoyancy and longer snouts for eating seagrass."

Gigantism evolved several times in sloths and likely contributed to their survival into the Pleistocene ice ages, when they reached their greatest sizes. But about 15,000 years ago many of these species abruptly vanished.

"[This] does not track with shifts in palaeotemperature, reinforcing the idea that human impacts played a more prominent role in the extinction of ground sloths than climatic change," the researchers conclude.

The bulk that kept giant sloths warm and saved them from local predators made them a target of Earth's most voracious predator: us. Their numbers dropped off massively once humans arrived in North America.

In contrast, the sluggish tree-climbers we know today seemed to have had more luck staying out of our reach, at least until more recently. Two of the six species still alive today are now on the IUCN endangered species lists.

Boscaini and team's findings echo an increasingly recognized global story: the rapid extinction of megafauna following the arrival of humans – a scenario that's still continuing today.

This research was published in Science.